Ankle Sprain

Pathophysiology

For stability the anterior talofibular ligament is the most important in plantarflexion. The calcaneofibular and posterior talofibular ligaments are the most important in dorsiflexion.

The anterior talofibular ligament is the most commonly injured. Injury to this ligament results in lateral instability of the ankle joint, abnormal anterior talar displacement from the mortise, and decreases the resistance to internal rotation of the talus within the mortise. The calcaneofibular ligament is the second most commonly injured ligament.

The injuries typically occur as a result of landed or falling on a plantarflexed and inverted ankle. However injury can also occur in a position of inversion, adduction, and dorsiflexion (rather than plantarflexion).

The incidence of injuries also matches the ligamentous strength. From weakest to strongest: anterior talofibular (139N), posterior talofibular (261N), calcaneofibular (346N), and deltoid (714N).[1]

Assessment

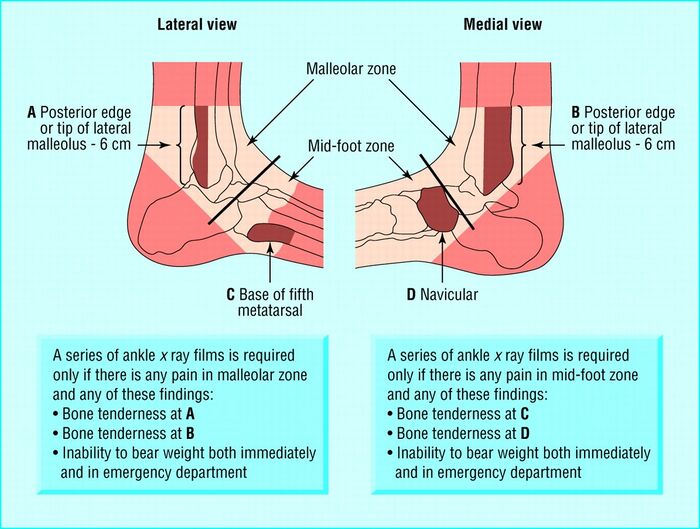

The Ottawa Ankle rule is an accurate instrument for excluding fractures of the ankle and mid-foot. Sensitivity is almost 100% and specificity is modest. It can be used to prevent unnecessary radiography in patients with suspected ankle sprains.[2]

A partial or complete lateral ankle ligament rupture is likely in the event of a haematoma accompanied by pain with palpation or a positive anterior drawer test or both. A delayed physical examination (4-5 days) is more accurate than 48 hours, with a sensitivity of 96% and specificity of 84% for detecting ligament rupture.[3]

Treatment

See Seah et al and Tiemstra et al for a review on management.[4][5]

- Mild to moderate ankle sprain: functional treatment options are better than immobilisation on multiple outcome measures. Functional treatment consists of elastic bandaging, soft casting, taping, or orthoses, with association coordination training

- Severe ankle sprain: This is controversial. It may be sensible to recommend 10 days of nonweightbearing and immobilisation in a cast or in a combination of a rigid splint and elastic bandage. Early functional rehabilitation can be initiated at the end of the period of immobilisation. A short period of immobilisation in a below-knee cast or pneumatic brace can result in a quicker recovery than tubular compression bandage alone.

- Supervised rehabilitation training in combination with conventional treatment for acute lateral ankle sprains can be beneficial, although some of the studies reviewed gave conflicting outcomes. Early mobilisation and focused range-of-motion exercises are preferred to prolonged rest.

- Cryotherapy can be used for the first 3-7 days to reduce pain and improve recovery time

- Lace-up supports are a more effective functional treatment than elastic bandaging and result in less persistent swelling in the short term compared to semi-rigid ankle supports, elastic bandaging, and tape.

- Semi-rigid orthoses and pneumatic braces provide beneficial ankle support and may prevent subsequent sprains during high-risk sporting activity.

- An air stirrup brace combined with an elastic compression wrap, or a lace-up support alone, reduces pain and recovery time after an ankle sprain and allows early mobilization.

- There is probably a role for surgical intervention in severe acute and chronic ankle injuries, but the evidence is limited.

Prevention

- Spraino is a novel low-friction patch that can be attached to the outside of sports shoes to minimise friction at the lateral edge and can reduce the risk of injury.[6]

- Patients at risk of reinjury should participate in a neuromuscular training program.

- Air stirrup braces, lace-up supports, and athletic taping can reduce the risk of ankle sprains during sports

Prognosis

The recovery is often incomplete. The recurrence rate is 73%, and 59% have disability and residual symptoms.[1]

References

- ↑ 1.0 1.1 Basic Biomechanics of the Musculoskeletal System - Nordin 4th edition 2012

- ↑ Bachmann, L. M., Kolb, E., Koller, M. T., Steurer, J., & ter Riet, G. (2003). Accuracy of Ottawa ankle rules to exclude fractures of the ankle and mid-foot: systematic review. BMJ : British Medical Journal, 326(7386), 417-417. retrieved from http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC149439/

- ↑ Kerkhoffs et al.. Diagnosis, treatment and prevention of ankle sprains: an evidence-based clinical guideline. British journal of sports medicine 2012. 46:854-60. PMID: 22522586. DOI.

- ↑ Seah, R. et al (2011). Managing ankle sprains in primary care: what is best practice? A systematic review of the last 10 years of evidence. Br Med Bull, 97, 105-135. doi:10.1093/bmb/ldq028

- ↑ Tiemstra, J. D. (2012). Update on acute ankle sprains. Am Fam Physician, 85(12),1170-1176.

- ↑ Lysdal FG, Bandholm T, Tolstrup JS, et alDoes the Spraino low-friction shoe patch prevent lateral ankle sprain injury in indoor sports? A pilot randomised controlled trial with 510 participants with previous ankle injuriesBritish Journal of Sports Medicine 2021;55:92-98.