Cauda Equina Syndrome

Cauda equina syndrome is a rare acute polyradiculopathy of the descending lumbar and sacral nerve roots. It is caused by a lesion in the spinal canal that causes compression of the cauda equina, most commonly from a massive lumbar disc prolapse. It is a clinical syndrome with either unilateral or bilateral progressive lumbosacral polyradiculopathy, back pain, saddle anaesthesia, recent disturbance of bladder function, and sometimes disturbance of bowel function. The condition is a neurologic emergency that requires urgent MRI and surgical review. If left untreated the patient can develop permanent neurological deficits.

Anatomy and Embryology

The spinal cord runs from the medulla oblongata to the level of T12-L1. The next caudal part of the spinal cord is the medullary cone. The cauda equina starts from the medullary cone and consists of the spinal nerves L2-L5, S1-S5, and the coccygeal nerve. These nerves are comprised of dorsal (sensory) and ventral (motor) nerve roots. The nerve root functions include sensory supply to the saddle region, voluntary control of the outer surface of the rectum, voluntary control of the urinary sphincters, and the sensory and motor innervation of the lower limbs. Dysfunction of the cauda equina can cause problems in the above functions. The cauda equina is situated in the thecal sac and is surrounded by cerebrospinal fluid in the subarachnoid space.[1]

The cauda equina starts forming in the third month of gestation, and the spinal cord extends the entire length of the body at this time. After this time, the verebtral column bones and cartilage grows faster than the spinal cord. This causes the nerves below the cervical spine to follow a slanted path. The lumbar and sacral nerves therefore move caudally and vertically inside the spinal canal, before exiting through the intervertebral foramina. The nerve roots below L1 form the cauda equina.[1]

Epidemiology

The syndrome occurs in 1-3% of all disc herniations. The prevalence is one case per 33,000-100,000 [1]

Aetiopathophysiology

Compression of the cauda equina can affected venous return to the cauda equina and sometimes interrupt the arterial supply. This leads to devitalised tissue and subsequently permanent loss of function of the territories supplied by the compressed nerve roots.[2] Lumbar disc herniation is the most common cause (45%), but anything that compresses the cauda equina can cause the syndrome including tumours, trauma, and infections.[1] This article focuses primarily on discogenic causes. There is an increased risk with obesity which is thought could be related to spinal epidural lipomatosis, reduced canal size, electrochemical behaviour, and inflammatory mediators.[2]

The list of causes of cauda equina syndrome are as follows:[3]

- Degenerative causes: lumbar disc herniation (most common, especially at L4/5 and L5/S1), lumbar spinal canal stenosis, spondylolisthesis, haemorrhage into a Tarlov cyst, facet joint cysts

- Inflammatory: both acute and chronic form may be seen in long-standing ankylosing spondylitis (2nd-5th decades; average 35 years), traumatic, spinal fracture or dislocation, epidural haematoma (may also be spontaneous, post-operative, post-procedural or post-manipulation)

- Infective: arachnoiditis, epidural abscess, tuberculosis (Pott disease), Herpes simplex virus, Elsberg syndrome.

- Tumours: primary, myxopapillary ependymoma, schwannoma, spinal meningioma, other tumours of the cauda equina, tumours in vertebral bodies, lymphoma, vertebral metastases, leptomeningeal carcinomatosis

- Vascular: aortic dissection, arteriovenous malformation - spinal dural arteriovenous fistula.

- Functional / Scan-Negative Cauda Equina Syndrome: In this setting symptoms are typically triggered by acute pain with or without nerve root impingement. In conjunction with medications, anxiety, and fear some vulnerable individuals have inhibition of normal voiding, more pain, and a negative brain-bladder feedback loop. The same processes in the brain also lead some susceptible individuals to functional neurological disorders leading to motor and sensory dysfunction in the legs.[4]

- Numerous other rare space-occupying lesions (e.g. sarcoid)

Clinical Presentation

- Bilateral radiculopathy (sensory or motor disturbance) or radicular pain

- Progressive neurological deficits in the legs

- Difficulties in micturition (including impaired bladder or urethral sensation, hesitancy, poor stream)

- Urgency of micturition with preserved control of micturition

- Subjective and/or objective loss of perineal sensation

- Possible red or white flags*: Impaired perineal sensation, Impaired anal tone

- White flags*: Urinary retention or incontinence, faecal incontinence, perineal anaesthesia

*White flags means surrender, i.e. the patient likely has irreversible cauda equina syndrome, and the diagnosis has been made too late[5]

Clinical features can include low back pain, unilateral or bilateral radicular pain and/or radiculopathy, reduced saddle region sensation, reduced sexual function, faecal incontinence, and bladder dysfunction. The onset of symptoms can be slow. Development of perineal dysfunction with bladder disturbance is commonly thought to be the onset of cauda equina syndrome. However the symptoms for cauda equina syndrome can be very non-specific.[2][6]

- Pain: Low back pain and radicular leg pain are common symptoms. Disc herniation is often associated with low back pain, and the pain can worsen in the supine position due to increased pressure on the compressed nerve roots. It is more common to have unilateral rather than bilateral radicular pain. There may be no leg symptoms at all if there is only compression of the central sacral and not the lateral lumbar nerve roots. The pattern of pain is dependent on the level of involvement (L2 to S3).[6]

- Bladder dysfunction: This is a hallmark feature of cauda equina syndrome and is present in most patients in some form. In the early stages bladder symptoms can be quite mild and the patient may not think much of them. Symptoms include reduced urethral sensation with micturition, urinary retention, and urinary incontinence. Urinary incontinence can manifest as overflow incontinence, but if this does not occur then retention may not otherwise be noted by the patient [6]Urinary dysfunction can be due to pain inhibition rather than cauda equina compression.[2]

- Bowel dysfunction: Bowel involvement is less common than bladder involvement. There is no consensus as to what constitutes bowel dysfunction. Symptoms include a feeling of rectal fullness, constipation, and faecal incontinence. In more severe disease, the patient may not notice bowel impairment due to the inability to sense rectal filling.

- Sexual dysfunction: Symptoms include erectile dysfunction, urination during intercourse, priapism, and dysparaeunia.[6]

- Sensory deficits: The most common regions of sensory deficit are the buttocks, posterior thighs, and perineal regions. 75% of patients have saddle anaesthesia. The doctor should assess for sensation using light touch and pinprick looking at the lower limbs, saddle region, and perineum. The loss of sensation may be mild, patchy, or unilateral.[6] Saddle anaesthesia has a high positive predictive value, but the absence of this cannot exclude the condition.[2]

- Weakness: There may be unilateral or bilateral weakness, and the myotomes may involve any distribution from L2 to S2. If the patient has compression of primarily the lower sacral or coccygeal nerve roots, then there may not be not be present which requires compression of the more lateral lumbar nerve roots. In the presence of weakness, the L5 to S2 nerve roots are the most commonly affected.[6]

- Reflexes: Both upper and lower extremity reflexes should be assessed. There may be reduced reflexes at the knees, medial hamstrings, and ankles. brisk knee jerks but a reduced or absent knee jerks suggests lower spinal cord involvement or a myeloneuropathy. The anal wink reflex is tested by applying a cotton-tipped applicator to the skin around the anus and observing the reflex contraction of the external anal sphincter. The bulbocavernosus reflex is assessed by applying pressure to the glans penis and observing the reflex contraction of the external anal sphincter. These two reflexes can be used as part of an assessment of the lower sacral nerve roots.[6]

- Rectal Exam: The rectal exam has three components: tone, saddle area sensation, and anal wink (discussed above). Concern should be raised if any of these three are diminished. Reduced rectal tone correlates with sensory loss in the saddle region but not with bladder dysfunction. There are data that show that rectal tone does not correlate with the presence of cauda equina syndrome. This may be due to the highly subjective nature and inaccurate test interpretation by clinicians.[6] It is imperative that normal anal tone is not a factor in deciding whether to do MRI imaging. A recent review concluded that rectal tone should not be assessed in any clinical setting due to high risk of false reassurance.[7]

Assessment Accuracy

Red flags used to identify potential cauda equina syndrome are more specific than sensitive. The pooled sensitivity for the typical signs and symptoms of cauda equina syndrome range from 0.19 to 0.43, and pooled specificity ranges from 0.62 to 0.88. Overall, it is not possible to exclude cauda equina syndrome on clinical assessment[8]

| Symptom/Sign | SN | SP | LR+ | LR- |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Saddle Anaesthesia | 0.38 (0.28-0.49) | 0.85 (0.81-0.89) | 2.00 (0.92-4.33) | 0.80 (0.61-1.05) |

| Reduced Anal Tone | 0.30 (0.16-0.49) | 0.83 (0.76-0.88) | 1.83 (1.00-3.33) | 0.90 (0.73-1.12) |

| Urinary Retention | 0.25 (0.17-0.35) | 0.72 (0.65-0.79) | 0.84 (0.53-1.32) | 0.99 (0.82-1.20) |

| Leg Pain | 0.43 (0.30-0.56) | 0.66 (0.59-0.73) | 1.50 (0.80-2.80) | 0.90 (0.61-1.30) |

| Urinary Incontinence | 0.24 (0.16-0.33) | 0.70 (0.61-0.77) | 0.76 (0.50-1.13) | 1.05 (0.92-1.20) |

| Bowel Incontinence | 0.19 (0.09-0.33) | 0.86 (0.80-0.91) | 1.60 (0.66-3.89) | 0.97 (0.78-1.20) |

| Back Pain | 0.34 (0.26-0.42) | 0.62 (0.51-0.72) | 1.98 (1.52-2.58) | 0.64 (0.26-1.60) |

Lumbosacral Nerve Root Function

| Nerve Root | Motor Function | Sensory Innervation | Reflexes |

|---|---|---|---|

| L2 | Hip flexion, thigh adduction | Proximal thigh | None |

| L3 | Lower leg extension, thigh adduction | Anterolateral thigh | Patella |

| L4 | Lower leg extension | Anteromedial lower leg | Patellar |

| L5 | Foot and toe dorsiflexion | Anterolateral leg, dorsal foot | Internal hamstring |

| S1, S2 | Foot and toe plantar flexion | Lateral, plantar foot; posterior thigh, lower leg | Ankle |

| S2, S3 | Anal sphincter | Perineal, saddle | Bulbocavernosus |

| S4, S5 | Urethral sphincter | None | None |

Definitions

- Cauda equina syndrome suspected (CESS) - for example bilateral radiculopathy, or subtle features.

- Cauda equina syndrome incomplete (CESI) - there is objective evidence of cauda equina syndrome but the patient still has voluntary control of urination. There may be other urination problems such as urgency, poor stream, hesitancy, and/or reduced bladder or urethral sensation, and may rely on external pressure for voiding.

- Cauda equina syndrome with retention (CESR) - there is complete urinary retention and overflow incontinence. [5]

Investigations

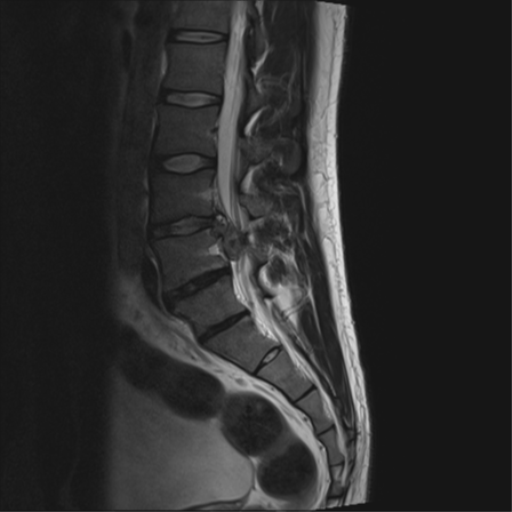

MRI without contrast is the investigation of choice. If the patient is unable to tolerate lying supine due to pain then the bare minimum are the sagittal and axial T2 sequences. If MRI is unavailable or there are contraindications then CT or CT myelogram are alternatives. See McNamee et al for an open access review of imaging.[9] MRI can assess for cauda equina compression, and determine the cause such as disc herniation, tumour, abscess, or haematoma. In the event of an absolute contraindication to MRI, other imaging options such as a CT myelogram is necessary. The definition of what "urgent" does not have an accurate definition, and timing can depend on the context of where the patient is being cared for and the services available. Regardless, it should be done as soon as possible.[2] Cauda equina syndrome is a clinical diagnosis, and therefore the correct terminology on MRI reporting is "compression of the cauda equina." For example, elderly patients with central canal stenosis may have compression of the cauda equina but not have cauda equina syndrome.[3]

It is imperative that within a health service that there is a high rate of negative MRIs in order to reduce the rate of missing cases, and so there should be a low threshold for urgent imaging. Put another way, if there is a high rate of positive MRI findings then the health service is likely missing cases at their early stages. In the correct clinical context, cauda equina syndrome cannot be discounted without MRI imaging ruling out cauda equina compression.[5]

Bladder volume scanning can be useful for detecting urinary retention. However a normal bladder scan does not exclude cauda equina syndrome, and this occurs in 40-60% of cases.[2]

Diagnosis

Cauda equina syndrome is a clinical rather than radiological diagnosis, but MRI can inform which patients with the clinical syndrome have cauda equina compression. The symptoms and signs are non-specific. Clinical features with the highest predictive value, for example painless urinary retention, are features of late often irreversible disease. The emphasis is on symptoms that are severe and progressive.[5] It is important to document the time of onset of bladder dysfunction because this is an important measure with respects to treatment and potential medicolegal assessments.[2]

There is no single symptom or sign of combination thereof that has a strong positive predictive value for diagnosing cauda equina syndrome before it is irreversible. Many of the red flags are subjective. It can be difficult to detect subtle perianal sensory deficits. Anal tone can also be difficult to interpret, and there is poor interobserver reliability.[5]

Most patients with signs of cauda equina syndrome do not have cauda equina compression. Patients with scan-negative cauda equina syndrome have high rates of chronic pain, psychiatric comorbidity, bladder dysfunction, and reduced social functioning. These patients commonly have typical symptoms of cauda equina compression such as reduced anal tone, saddle numbness, and urinary retention. Urgent MRI is still warranted even when suspicion for a functional disorder is high.[4]

An important differential diagnosis is conus medullaris syndrome. The primary difference between the two syndromes is that conus medullaris syndrome causes mixed upper motor neurone and lower motor neurone deficits, while cauda equina syndrome causes purely lower motor neurone deficits.

- Conus medullaris syndrome

- Lumbosacral disc herniation (eg, L5-S1 radiculopathy)

- Scan-Negative Cauda Equina Syndrome

- Spondylolisthesis

- Lumbar spinal stenosis

- Spinal cord infarction

- Spinal cord tumour

- Spinal cord abscess (eg, paraspinal, epidural)

- Ankylosing spondylitis

- Tethered cord

- Diastematomyelia

- Diabetic neuropathy

- Guillain-Barré syndrome

- Polyradiculitis

- Lumbosacral plexopathy

- Neurosarcoidosis

- Multiple sclerosis (usually hyperreflexia, however)

- Vascular claudication

Treatment

Cauda equina syndrome is a neurological emergency. It is imperative that the condition is recognised and decompressive surgery occurs before the onset of CESR if possible. Surgery should be extensive to allow complete decompression of the cauda equina. However this can be difficult where there is stretching of the thecal sac over a massive central disc prolapse. The presence of bladder function before decompression, and decompression before 48 hours are factors associated with improved outcomes.[2]

Patients treated at the point of CESS with bilateral radicular pain or bilateral radiculopathy are at risk of cauda equina syndrome from a central disc prolapse but do not have the syndrome at that point in time. Good outcomes are achieved if decompressive surgery is performed.[5]

If treated at the stage of CESI with incomplete clinical features, there is a reduced chance of developing more severe disease with painless urinary retention. The longterm bladder function is good, but there may be some symptoms of urgency or other symptoms that don't require catheterisation. There may be longterm sexual dysfunction if there was genital sensory loss prior to treatment. However overall good outcomes are seen with decompressive surgery for most patients.[5] The data available indicate poorer outcomes with longer delays to treatment for CESI, and a delay longer than 48 hours leads to poorer outcomes.[2]

If treated at the point of CESR with urinary retention, many patients have permanent severe impairment of cauda equina function with a paralysed insensate bladder and bowel that requires intermittent self-catheterisation, manual evacuation of faeces and/or bowel irrigation, and generally no significant sexual function. Only a small proportion of patients with severe deficits return to work. The timing of surgery after CESR develops is controversial, and recovery of function is more likely if there is some perineal sensation preoperatively.[5] There is unlikely to be improvement in CESR after 48 hours.[5]

Summary

- Cauda equina syndrome is a clinical diagnosis confirmed on imaging, and is classified into CESS (suspected), CESI (incomplete), and CESR (retention).

- Bladder, bowel, or sexual dysfunction in combination with saddle or perineal sensory deficit is needed to make a clinical diagnosis. The patient may have back pain, lower limbs weakness, lower limb sensory loss, and abnormal lower limb reflexes.

- Urinary symptoms include reduced urethral sensation while voiding, urinary retention, and overflow urinary incontinence. Urinary retention confers a poor prognosis and the diagnosis has been made too late (white flag).

- Disc herniation at L4-L5 and L5-S1 are the most common causes

- Disc herniation if only centrally located, may not compress the lateral lumbar nerve roots, and so the patient may not have lower limb pain or neurological deficit.

See Also

References

- ↑ 1.0 1.1 1.2 1.3 Kapetanakis et al.. Cauda Equina Syndrome Due to Lumbar Disc Herniation: a Review of Literature. Folia medica 2017. 59:377-386. PMID: 29341941. DOI.

- ↑ 2.0 2.1 2.2 2.3 2.4 2.5 2.6 2.7 2.8 2.9 Quaile. Cauda equina syndrome-the questions. International orthopaedics 2019. 43:957-961. PMID: 30374638. DOI.

- ↑ 3.0 3.1 Ian Bickle and Henry Knipe et al. Cauda equina syndrome. Radiopaedia. Accessed 16/5/2021. Link

- ↑ 4.0 4.1 Hoeritzauer I, Carson A, Statham P, Panicker JN, Granitsiotis V, Eugenicos M, Summers D, Demetriades AK, Stone J. Scan-Negative Cauda Equina Syndrome: A Prospective Cohort Study. Neurology. 2021 Jan 19;96(3):e433-e447. doi: 10.1212/WNL.0000000000011154. Epub 2020 Nov 11. PMID: 33177221.

- ↑ 5.0 5.1 5.2 5.3 5.4 5.5 5.6 5.7 5.8 Todd. Guidelines for cauda equina syndrome. Red flags and white flags. Systematic review and implications for triage. British journal of neurosurgery 2017. 31:336-339. PMID: 28637110. DOI.

- ↑ 6.0 6.1 6.2 6.3 6.4 6.5 6.6 6.7 6.8 Goodman. Disorders of the Cauda Equina. Continuum (Minneapolis, Minn.) 2018. 24:584-602. PMID: 29613901. DOI.

- ↑ Tabrah, Julia; Wilson, Nicky; Phillips, Dean; Böhning, Dankmar (2022-04-01). "Can digital rectal examination be used to detect cauda equina compression in people presenting with acute cauda equina syndrome? A systematic review and meta-analysis of diagnostic test accuracy studies". Musculoskeletal Science and Practice (in English). 58: 102523. doi:10.1016/j.msksp.2022.102523. ISSN 2468-7812.

- ↑ 8.0 8.1 Dionne et al.. What is the diagnostic accuracy of red flags related to cauda equina syndrome (CES), when compared to Magnetic Resonance Imaging (MRI)? A systematic review. Musculoskeletal science & practice 2019. 42:125-133. PMID: 31132655. DOI.

- ↑ McNamee et al.. Imaging in cauda equina syndrome--a pictorial review. The Ulster medical journal 2013. 82:100-8. PMID: 24082289. Full Text.

- ↑ Cauda equina syndrome. Visual Dx. Link

Literature Review

- Reviews from the last 7 years: review articles, free review articles, systematic reviews, meta-analyses, NCBI Bookshelf

- Articles from all years: PubMed search, Google Scholar search.

- TRIP Database: clinical publications about evidence-based medicine.

- Other Wikis: Radiopaedia, Wikipedia Search, Wikipedia I Feel Lucky, Orthobullets,