Coccydynia

Coccydynia is also known as coccygodynia or tailbone pain. This pain condition normally resolves with supportive care but can occasionally become persistent. The effects on quality of life can be dramatic. Dynamic (standing and sitting) radiography is the most important investigation. Pathological findings are hypermobility, luxation, and the presence of a spicule in a rigid coccyx.

Anatomy

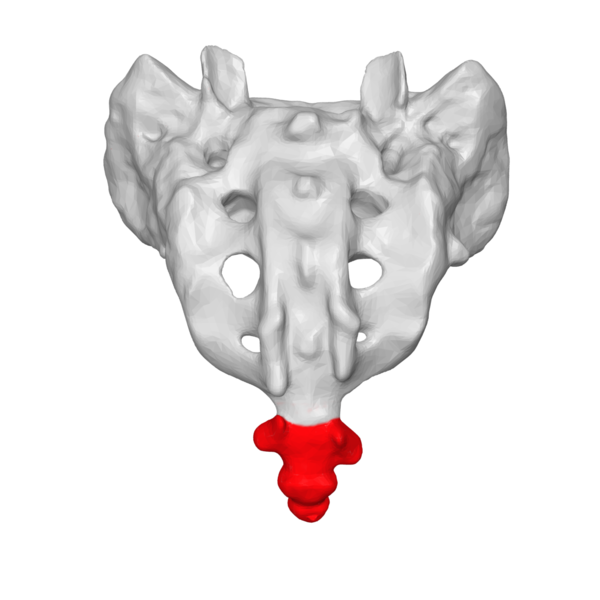

- Main article: Coccyx Anatomy

The coccyx has between three to five vertebrae. Four segments is the most common, followed by five, then three. There is also a significant rate of intercoccygeal joint fusions, which is most prominent in the most caudal joint. Fusion of the whole structure into one segment is uncommon. The intercoccygeal angle is 135°, with a higher angle in those with a single segment. The intercoccygeal joints are variable. They can consist of complete intervertebral discs, partial discs, synovial joints, or they can be fused. [1] The coccyx is the insertion site for multiple muscles, ligaments, and tendons.

Epidemiology and Risk Factors

The overall prevalence is unknown.[2] The female to male ratio is 5:1.[2] The coccyx is more posteriorly located and longer in women, which are thought to be risk factors for trauma.[2] It is also more common in obese individuals,[2] and in those with sacrococcygeal joint fusion.[3]

There is a significant relation of BMI with the culprit radiographic pain generator, with a more marked relation in women. Obesity is associated with having a backwards moving coccyx, reduced sagittal pelvic rotation, and a higher angle of incidence (The angle that the coccyx strikes the seat). In other words when the obese individual goes to sit, they tend to fall into the seat with insufficient pelvic rotation, and the coccyx sticks out more posteriorly becoming susceptible to repetitive microtrauma.[4]

A normal or low BMI is associated with having a forward moving coccyx and having pain from hypermobility, spicules, or pain without radiographic abnormalities. Lower BMIs are associated with more pelvic sagittal rotation and shallower angles of incidence allowing the coccyx to be protected from a fall. The rare anterior luxation is also more common in lower BMI individuals.[4]

A history of trauma is predictive of the presence of luxation if sustained within a month of evaluation.

Aetiology

- Falling backwards into a sitting position - The most common cause which can cause bruising, fracture, or dislocation.[2]

- Repetitive microtrauma - such as from prolonged sitting on certain surfaces.[2]

- Instability - sacrococcygeal joint hyper- or hypomobility, or coccygeal joint dynamic hypermobility on sitting and standing radiographic comparisons.[2]

- Childbirth and forceps delivery.[5]

- Posterior bone spicule - found on the dorsal aspect of the tip of the coccyx.[2]

- Osteoarthritis.[2]

- Rare causes - CRPS, infection, metastatic malignancy, CPPD, Chordomas, Benign notochordal cell tumours, avascular necrosis, sacral nerve arachnoiditis, glomus tumour, precoccygeal dermoid cyst.[2]

In adolescents abnormal mobility is rarer and spicules are more frequent[6]

Clinical Features

History

One should evaluate for any history of trauma. The patient generally can pin point the area of pain, which is much more caudal than the normal areas of low back pain. Sitting is normally painful but this may be reduced upon leaning forward and taking the pain off the coccyx. Transitional movements from sitting to standing can sometimes provoke pain and this is a moderately predictive feature on history of coccygeal pathology[4]. Sexual intercourse and passing bowel motions can also be painful. There may be radiation to the pelvic floor. Red flag symptoms should be evaluated.[2] One third of people have back pain.[7]

Examination

There is normally a well localised area of tenderness externally. Spicules can often be palpated externally, and there is usually a pit overlying this, or slightly higher in the natal cleft. Pits are normally subtle, but rarely there can be a frank retrococcygeal pilonidal sinus, thought to be of embryonic origin.[4] The presence of pelvic obliquity should be evaluated. The dorsal sacroiliac ligaments and muscles should be palpated and assessed.

Per rectal examination can be performed to evaluate the coccyx internally, as well as to evaluate for haemorrhoids, rectal malignancy, and prostatic disease.[3] For bimanual examination of the coccyx, the index finger is inserted per rectum while the thumb holds the external surface of the coccyx. The coccyx can be moved and pain can be evaluated and compared to surrounding muscular and ligamentous structures.[2]

The BMI should be calculated as this has major associations with the expected radiographic lesion.[4]

Diagnosis and Imaging

The diagnosis is generally made clinically with corroborating features of history and examination. In those with mild symptoms without significant trauma imaging is not required. [2]

Obtain coccygeal imaging in those with with severe pain and significant trauma, or persistent pain. Red flag symptoms should be evaluated with imaging or other further investigations as appropriate, which is normally MRI.[2]

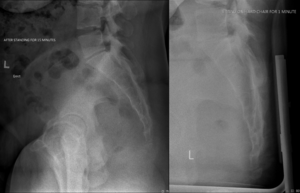

XR Imaging

- AP and lateral xrays

These can be helpful in evaluating for fracture, dislocation, hypermobility, bone spurts, and osteoarthritis.[2] Xray imaging can also be used to assess for scoliosis, the number and morphology of segments, and the intercoccygeal angle (the angle between the first and last coccygeal segment). The normal coccyx lies at a pivot angle of between 5 and 25 degrees. Angles outside of these ranges signify rigid mobility or hypermobility respectively.[8]

- Dynamic XR Imaging (coccygeal stress views)

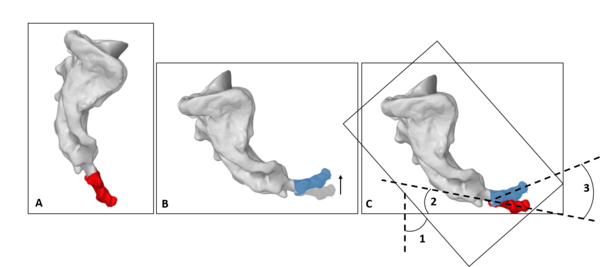

The coccyx normally flexes on sitting but may be immobile or extend.[4] Dynamic imaging is used to assess for this movement, as well as to evaluate the sagittal rotation of the pelvis and coccygeal angle of incidence.[8] These views can identify the source of pain in around 70% of patients[4]. The initial standing lateral radiograph is taken after 10 minutes of standing. The second sitting radiograph must be obtained in the most painful seated position. The two images are superimposed to assess for the relative movements of the sacrum and coccyx.[4]

Hypermobility in flexion has been defined as flexion of more than 25 degrees.[2] Hypomobility has been defined as less than 5 degrees. Any listhesis (subluxation) should also be assessed, which is normally posterior, but rarely anterior. Listhesis is defined as more than 25 percent of the coccygeal vertebral body while sitting in the non-hypermobile coccyx.[2] Posterior listheses are more common in type I coccyges(straighter variants), while the rarer anterior listheses are more common in type III and IV coccyges (more flexed variants).[4]

The coccygeal angle of incidence is defined as the angle where the coccyx hits the seat while sitting. This angle determines the direction of sagittal movement of the coccyx. A low angle is a coccyx roughly parallel with the seat. This will tend to cause flexion. Meanwhile a large angle, where the coccyx is roughly perpendicular to the seat, will cause the coccyx to extend. This may be related to increased pelvic pressure. Normal values are roughly 0 to 30°. Patients with reduced pelvic sagittal rotation (<30°) tend to have higher angles of incidence(mean 48°). While those with increased pelvic sagittal rotation(>40°)tend to have a lower angle of incidence (mean <20°).[4]

- Coned down lateral views (bone spurs)

Coned down views can be used to image for bone spurs. A collimator is used to improve image quality.[2] Evaluation for the presence of a spicule is essential as this is a common cause of pain in immobile coccyges, where the coccygeal tip isn’t able to move out of the way.[4] They can also be seen on MRI.

Radiographic Classification

The Postacchini and Massobrio classification classifies the coccyx based on kyphotic angulation and/or subluxation, with a decreasing order of frequency.[9] Coccydynia is more common in type III and IV coccyges.[7] Maigne found that luxation of the most caudal segment more commonly occured in the rarer anterior direction in the more curved types III and IV, while posterior luxation was more common in straighter type I. Spicules were more common in immobile coccyges. Flexion of more than 35 degrees, luxation, and spicules in a rigid coccyx are pathologic.[4]

| Author | Classification |

|---|---|

| Postacchini and Massobrio | Type I: Curved slightly forward |

| Type II: More marked curve, straight forward | |

| Type III: Sharply angled anteriorly | |

| Type IV: Subluxation of the sacrococcygeal or intercoccygeal joints | |

| Maigne (dynamic radiography) | Rigid coccyx |

| Normal mobility (5–25 degrees of flexion or extension) | |

| Hypermobility (25 degrees of flexion) | |

| Luxation (rearwards displacement of the coccyx in the seated position, spontaneously reducible in the standing position) |

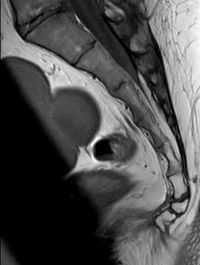

MRI Imaging

This should include T1 and T2 sagittal sequences, as well as a STIR image to show oedema.[2] MRI features include a rigid coccyx with a spicule at the caudal tip, a bursa along the dorsal surface, fluid collection within the sacrococcygeal synchondrosis, a large vein ventrally, and peri-coccygeal inflammation.[8]

MRI abnormalities are usually found at the tip in immobile coccyges, and within the joints in mobile coccyges.[10]

Differential Diagnosis

- Coccygeal disorders: fracture or dislocation, sacrococcygeal joint hyper or hypomobility, coccygeal joint hypermobility, bone spicule

- Referred spinal pain

- Pelvic floor or pelvic organ disease: endometriosis, prostatitis, PID, levator ani syndrome, etc.

- Pilonidal sinus

- Proctalgia fugax

- Rare causes - CRPS, infection, metastatic malignancy, CPPD, Chordomas, Benign notochordal cell tumours, avascular necrosis, sacral nerve arachnoiditis, glomus tumour, precoccygeal dermoid cyst.

Diagnosis

The diagnosis is made on clinical and radiographic features as described. A local anaesthetic injection can be used to confirm the diagnosis. In this way a culprit lesion can be identified 70% of the time. [4]

Prognosis

90% of cases resolve with conservative management or without medical input.[2] Pain is less likely to resolve in those when it has developed without an initial traumatic event.[2]

Management

The overall research quality is very poor in the management of coccydynia, a review of treatment approaches was done by Elkhashab et al in 2018[3]

Conservative Management

Initial management should include protection and analgesia, and this should be pursued for at least two months. Wedge or donut cushions can be used to offset the pressure away from the coccyx. The wedge cushion has a wedge shape cut out of the back of the cushion, while donut cushions have a hole in the centre. Wedge cushions are generally more helpful. A DIY solution can be done by cutting out a wedge from 5-10cm foam rubber.[2]

Steroid Injections

Injections with local anaesthetic with or without a corticosteroid may be helpful, especially in those with instability or bone spurs. The injections should be directed to an anatomic problem where possible, such as the individual coccygeal joints, sacrococcygeal junction, bone spur, ganglion impair, or the caudal epidural space. Injection under fluoroscopy may be required. [2]

Prolotherapy

Prolotherapy can be considered. Khan et al reported positive results in a case series using 2-3 injections of 25% dextrose in lidocaine, injected at the most tender spot, using an image intensifier to identify the sacrococcygeal joint. [11]

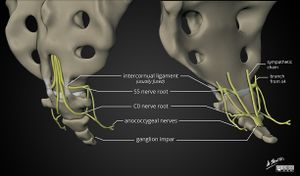

Ganglion Impar Treatments

- Main article: Ganglion Impar Injection

The ganglion impair is a midline sympathetic ganglion anterior to the upper coccyx, formed by the caudal termination of paired sympathetic chains. The ganglion provides both sympathetic and visceral innervation to the coccyx, perineum, and anal regions. The size and location can vary, and in some people the ventral ramus of the sacral nerve roots run close by. It is classically at the level of the sacrococcygeal junction.

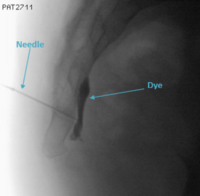

Injection treatment with corticosteroid and local anaesthetic is a procedure done in some centres. Radiofrequency treatments such as pulsed radiofrequency is a newer technique and may provide better results than blockade.[12]

Needle placement is generally done by piercing through the sacrococcygeal disc space. Fluoroscopic guidance is safer than ultrasound due to the inability on ultrasound to see ventral to the Sacrococcygeal disc space where the bowel in located. However with fluoroscopy it is often difficult to visualise the sacrococcygeal junction due to bowel gas and so combined imaging can improve accuracy and safety. In this method the needle is inserted by ultrasound, and then the depth confirmed on lateral fluoroscopy. Injection by ultrasound guidance alone is not recommended.[13]

Physiotherapy

Pelvic floor physiotherapy may be indicated in those with significant pelvic floor myofascial pain, such as with pain more anterior and inferior to the coccyx, rather than on the coccyx itself.[2] Stretching of the iliopsoas and piriformis muscle and oscillatory thoracic mobilisation was more effective than seat cushioning with sitz baths and phonophoresis in one RCT.[14]

Intrarectal Manipulation

Manipulation can worsen symptoms in those with hypermobility, fractures, and bone spurs. Manipulation is done via the rectum and can include levator ani massage.[2] Intrarectal manual therapy had a mild benefit over external physiotherapy in one RCT.[15]

Surgery

Surgery generally involves either complete coccygectomy with excision proximal to the sacrococcygeal junction, or partial coccygectomy leaving the upper coccygeal vertebra. Surgery has a 10% complication rate, and a 30% failure rate.[2]

Radiofrequency Ablation

An experimental treatment is radiofrequency ablation of the sacrococcygeal nerves, however there are no randomised controlled trials on this intervention. There has been observational research[16]

See Also

External Links

- coccyx.org this website also collates probably all the research into Coccydynia

- Medscape summary

- tailbonedoctor.com

References

- ↑ Tetiker et al.. MRI-based detailed evaluation of the anatomy of the human coccyx among Turkish adults. Nigerian journal of clinical practice 2017. 20:136-142. PMID: 28091426. DOI.

- ↑ 2.00 2.01 2.02 2.03 2.04 2.05 2.06 2.07 2.08 2.09 2.10 2.11 2.12 2.13 2.14 2.15 2.16 2.17 2.18 2.19 2.20 2.21 2.22 2.23 2.24 2.25 Foye, M. Coccydynia (coccygodynia). In: UpToDate, Post, TW (Ed), UpToDate, Waltham, MA, 2020.

- ↑ 3.0 3.1 3.2 Elkhashab & Ng. A Review of Current Treatment Options for Coccygodynia. Current pain and headache reports 2018. 22:28. PMID: 29556817. DOI.

- ↑ 4.00 4.01 4.02 4.03 4.04 4.05 4.06 4.07 4.08 4.09 4.10 4.11 4.12 Maigne et al.. Causes and mechanisms of common coccydynia: role of body mass index and coccygeal trauma. Spine 2000. 25:3072-9. PMID: 11145819. DOI.

- ↑ Maigne et al.. Postpartum coccydynia: a case series study of 57 women. European journal of physical and rehabilitation medicine 2012. 48:387-92. PMID: 22820826.

- ↑ Maigne et al.. Chronic coccydynia in adolescents. A series of 53 patients. European journal of physical and rehabilitation medicine 2011. 47:245-51. PMID: 21597433.

- ↑ 7.0 7.1 Kwon et al.. Coccygodynia and coccygectomy. Korean Journal of Spine 2012. 9:326-33. PMID: 25983841. DOI. Full Text.

- ↑ 8.0 8.1 8.2 Radiopaedia[Internet]. Coccydynia [cited 2020 July 24]. Available from: https://radiopaedia.org/articles/coccydynia

- ↑ Postacchini & Massobrio. Idiopathic coccygodynia. Analysis of fifty-one operative cases and a radiographic study of the normal coccyx. The Journal of bone and joint surgery. American volume 1983. 65:1116-24. PMID: 6226668.

- ↑ Maigne et al.. Magnetic resonance imaging findings in the painful adult coccyx. European spine journal : official publication of the European Spine Society, the European Spinal Deformity Society, and the European Section of the Cervical Spine Research Society 2012. 21:2097-104. PMID: 22354690. DOI. Full Text.

- ↑ Khan et al.. Dextrose prolotherapy for recalcitrant coccygodynia. Journal of orthopaedic surgery (Hong Kong) 2008. 16:27-9. PMID: 18453654. DOI.

- ↑ 12.0 12.1 Sir & Eksert. Comparison of block and pulsed radiofrequency of the ganglion impar in coccygodynia. Turkish journal of medical sciences 2019. 49:1555-1559. PMID: 31652036. DOI. Full Text.

- ↑ Lin et al.. Ultrasound-guided ganglion impar block: a technical report. Pain medicine (Malden, Mass.) 2010. 11:390-4. PMID: 20447308. DOI.

- ↑ Mohanty & Pattnaik. Effect of stretching of piriformis and iliopsoas in coccydynia. Journal of bodywork and movement therapies 2017. 21:743-746. PMID: 28750995. DOI.

- ↑ Maigne et al.. The treatment of chronic coccydynia with intrarectal manipulation: a randomized controlled study. Spine 2006. 31:E621-7. PMID: 16915077. DOI.

- ↑ Chen et al.. Radiofrequency Ablation in Coccydynia: A Case Series and Comprehensive, Evidence-Based Review. Pain medicine (Malden, Mass.) 2017. 18:1111-1130. PMID: 28034983. DOI.

Literature Review

- Reviews from the last 7 years: review articles, free review articles, systematic reviews, meta-analyses, NCBI Bookshelf

- Articles from all years: PubMed search, Google Scholar search.

- TRIP Database: clinical publications about evidence-based medicine.

- Other Wikis: Radiopaedia, Wikipedia Search, Wikipedia I Feel Lucky, Orthobullets,