Hip Labral Tear: Difference between revisions

| Line 44: | Line 44: | ||

===Conservative Management=== | ===Conservative Management=== | ||

An initial trial of non-operative management is recommended.<ref name="brukner"/> Physical therapy is aimed as minimising dynamic FAIT and reducing abnormal loads on the labrum | An initial trial of non-operative management is recommended.<ref name="brukner"/> Physical therapy is aimed as minimising dynamic FAIT and reducing abnormal loads on the labrum. <ref name=uptodate/> | ||

#Pelvic tilt should be optimised to reduce dynamic FAI. This can be done through pelvic girdle strengthening, gluteus maximus activation, abductor control, transversus abdominis and rectus abdominis activation, iliopsoas stretching, adductor stretching, rectus femoris stretching, core control, and pelvic floor control. <ref name="Harris"/> Exercises should start unloaded and progress with more load added.<ref name="brukner"/> | #Pelvic tilt should be optimised to reduce dynamic FAI. This can be done through pelvic girdle strengthening, gluteus maximus activation, abductor control, transversus abdominis and rectus abdominis activation, iliopsoas stretching, adductor stretching, rectus femoris stretching, core control, and pelvic floor control. <ref name="Harris"/> Exercises should start unloaded and progress with more load added.<ref name="brukner"/> | ||

| Line 52: | Line 52: | ||

Activity modification should also be discussed. The patient should be advised to avoid repetitive hip flexion, adduction, abduction, and rotation at end range. | Activity modification should also be discussed. The patient should be advised to avoid repetitive hip flexion, adduction, abduction, and rotation at end range. | ||

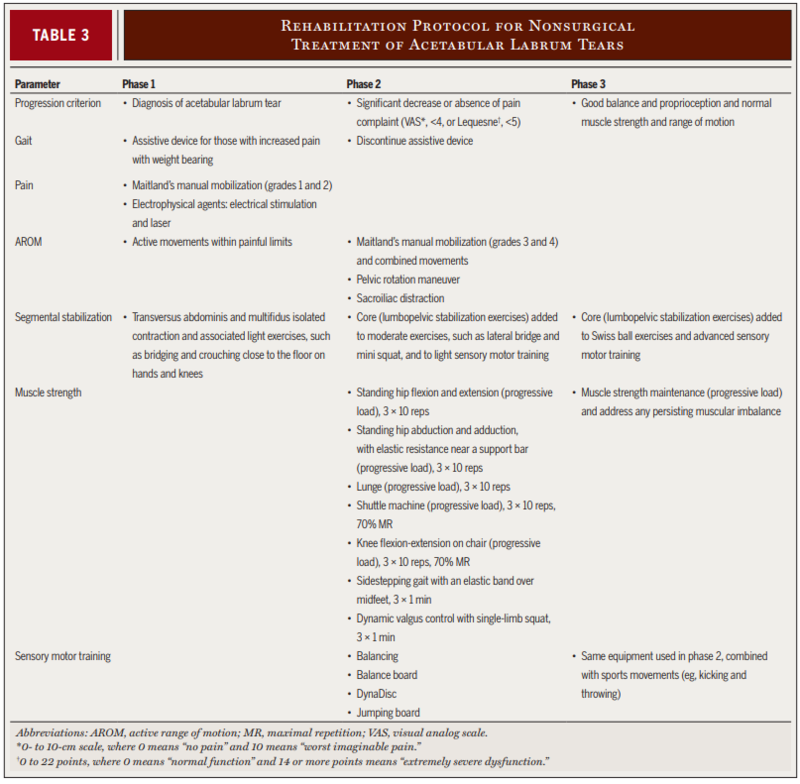

The evidence for physical therapy in symptomatic hip labral tears is very limited. A physical therapy progression program was described in a case series of four young patients with positive outcomes. Phase 1 emphasised pain control, education in trunk stabilization, and correction of abnormal joint movement. Phase 2 focused on muscular strengthening, recovery of normal range | |||

of motion (ROM), and initiation of sensory motor training. Phase 3 emphasised advanced sensory motor training, with sport-specific functional progression. <ref>{{#pmid:21335929|Yazbek}}</ref> | |||

[[File:Yazbek progression program.PNG|800px]] | |||

From Yazbek et al<ref name="Yazbek"/> | |||

===PRP=== | ===PRP=== | ||

Revision as of 19:50, 14 July 2020

Acetabular labral tears are a common cause of hip and groin pain in athletes and in those with degenerative hip joint conditions. Optimal diagnosis and management remains unknown, and due to the very high prevalence of asymptomatic tears the clinician is urged to treat the patient not the MRI.

Anatomy

The acetabular labrum is a fibrocartilaginous structure that seals the central hip joint from the periphery, keeps the synovial fluid within the central compartment, and creates a negative pressure within the joint. It increases the depth, volume, surface area, and congruity of the hip joint. The negative pressure helps to resist subluxation of the femoral head and increases stability.

Any disruption of the labrum can negatively affect articular cartilage health and joint stability.[1] On the other hand, labral tears are extremely common in the asymptomatic population, and it is still not completely known which types of tears are clinically important and may become symptomatic.[2]

The vascular supply originates from the radial branches of a periacetabular periosteal vascular ring, which arises mainly from the superior and inferior gluteal arteries. The vessels course over the periosteum, and penetrate the through the capsule and connective tissue, ending at the free edge of the labrum. Therefore the vascular supply remains intact even with a tear at the chondrolabral junction.[3]

Nociceptive fibres are found at the highest density in the anterior labrum, but course mostly anterosuperiorly to posterosuperiorly. This is also the typical area of labral pathology. The free nerve endings are located primarily at the labral base, and decrease peripherally, being mostly superficial on the chondral surface. The fibres arise mainly from the obturator nerve and the nerve to the quadratus femoris. Proprioceptive end organs are also found within the labrum.[3]

Epidemiology

Labral tears are present in 22% of athletes with groin pain and 55% of those with mechanical symptoms.[4] Ligamentum Teres Tears are found in 70% of sportspeople's hips when undergoing arthroscopy for FAI or labral tears.[4] In a well done study of young asymptomatic volunteers in a ski town, approximately 69% had a labral tear, and other hip pathology was also common such as 24% having a chondral lesion. In addition, 95% of those with FAI also had a labral tear.[2]

Pathogenesis

There are two general mechanisms of injury to the acetabular labrum.[1]

- Traumatic tears: A single event of significant trauma. This normally involves forced resistance of hip flexion while kicking or running (for example in Rugby).

- Degenerative tears:Repetititve injury and microtrauma in an osteoarthritic, dysplastic hip or in a hip with FAI.

Pathology normally occurs in the weightbearing anterosuperior aspect of the labrum.[1] There are several thoughts as to the reasons for this prediliction. There is reduced thickness of the anterior labrum. Femoroacetabular impingement normally causes anterior impingement. Repetitive twisting and pivoting is a factor. Owing to anteversion of the acetabulum, there is reduced bony support anteriorly which may also increase the shear forces on the labrum. Increased forces are also placed on the anterior labrum during the final stages of the stance phase of gait and in more than 5 degrees of hip extension.[4]

Healing of the labrum has been demonstrated in animal studies.[5]

Classification

Type I tears are a detachment of the labrum from the acetabular rim cartilage. Type II is a cleavage tear within the labrum substance. The tear location in respect to vascular supply is important when considering healing potential.[4]

It is still not known which types of tears are pathological and which may be normal variants.[2]

Clinical Features

The most common symptom is groin pain that is exacerbated by athletic activity. Pain is normally located in the anterior hip or groin, and is often described as sharp. Uncommonly it can can cause mechanical symptoms such as catching, clicking, or locking. [1]Some patients may describe buttock pain.[4] Pain can occur in particular with activities involving aggressive hip flexion such as jumping or sprinting. Pain can sometimes occur when fatigued such as during a long distance run, or running up hill. Some patients may report groin pain with sitting, transitioning between standing from sitting, or when descending stairs. Some activities of daily living may be affected such as putting on shoes or stockings while sitting. [1]

Examination has poor sensitivity and sensitivity.[4] Features are pain with hip flexion and anterior impingement tests. No test is specific for labral injury, and signs and symptoms overlap with FAI. Some useful tests are repeated hip flexion, hip flexion against resistance, FABER, and FADDIR testing. Reduced internal rotation may suggest hip joint osteoarthritis.[1][4]

The ligamentum teres test can be performed if a tear of this structure is suspected. This involves the patient being supine, flexing the hip to full flexion minus 30 degrees, abducting to full abduction minus 30 degrees, them moving the hip internally and externally through full range of motion. A positive test is reported pain.[4]

Imaging

MRA is the most accurate imaging modality, but the gold standard remains the arthroscopic exam[4]. Xrays can be helpful, and should include standing anteroposterior, cross-table lateral or Dunn lateral, and a false profile view. An intraarticular injection of local anaesthetic with or without a glucocorticoid can aid in the diagnostic process if pain is ablated following injection. If an MRA is performed then anaesthetic can be injected along with the contrast and a pain diary can be ascertained.

Management

Conservative Management

An initial trial of non-operative management is recommended.[4] Physical therapy is aimed as minimising dynamic FAIT and reducing abnormal loads on the labrum. [1]

- Pelvic tilt should be optimised to reduce dynamic FAI. This can be done through pelvic girdle strengthening, gluteus maximus activation, abductor control, transversus abdominis and rectus abdominis activation, iliopsoas stretching, adductor stretching, rectus femoris stretching, core control, and pelvic floor control. [3] Exercises should start unloaded and progress with more load added.[4]

- Optimise sagittal balance with the spine and pelvis, factors remote from the hip joint affecting biomechanics.[3]

- Gait retraining can also be considered in order to reduce excessive hip extension at the end of the stance phase of gait.[4]

Activity modification should also be discussed. The patient should be advised to avoid repetitive hip flexion, adduction, abduction, and rotation at end range.

The evidence for physical therapy in symptomatic hip labral tears is very limited. A physical therapy progression program was described in a case series of four young patients with positive outcomes. Phase 1 emphasised pain control, education in trunk stabilization, and correction of abnormal joint movement. Phase 2 focused on muscular strengthening, recovery of normal range of motion (ROM), and initiation of sensory motor training. Phase 3 emphasised advanced sensory motor training, with sport-specific functional progression. [6]

From Yazbek et al[7]

PRP

A small prospective study of 8 people reported positive outcomes with the injection of PRP at the site of labral tear at 8 weeks of follow up.[8]

Surgery

Arthroscopic surgery can be considered upon failure of conservative management and is aimed at treating the labrum and the underlying cause.[3] In athletes with FAI, surgery can be considered early if their sport requires a range of motion not achieved before impingement symptoms occur.[4] Where possible the labrum should be restored rather than simply debrided in order to restore the normal hip joint seal and this probably provides better outcomes. The removal of damaged tissue and replacement with a graft may aid in pain reduction due to the presence of nociceptive fibres within the labrum. Proprioceptive fibres are also removed and so it is important to be mindful of overly stressing the graft postoperatively. The labrum can also be repaired in some instances as another operative option. [3]

There are no randomised sham controlled trials for arthroscopy surgery, and so surgical treatment remains unproven. A systematic review and meta-analysis of 8 level 3-4 observational studies showed positive outcomes, and no difference between allograft vs autograft.[9]

Contraindications are contraindications to hip preservation surgery rather than labral repair itself. They include significant hip osteoarthritis, or in combination with uncorrected dysplasia. There is no role for prophylactic repair in the asymptomatic population.[3]

References

- ↑ 1.0 1.1 1.2 1.3 1.4 1.5 1.6 Johnson, R. Approach to hip and groin pain in the athlete and active adult. In: UpToDate, Post, TW (Ed), UpToDate, Waltham, MA, 2020.

- ↑ 2.0 2.1 2.2 Register et al.. Prevalence of abnormal hip findings in asymptomatic participants: a prospective, blinded study. The American journal of sports medicine 2012. 40:2720-4. PMID: 23104610. DOI.

- ↑ 3.0 3.1 3.2 3.3 3.4 3.5 3.6 Harris. Hip labral repair: options and outcomes. Current reviews in musculoskeletal medicine 2016. 9:361-367. PMID: 27581790. DOI. Full Text.

- ↑ 4.00 4.01 4.02 4.03 4.04 4.05 4.06 4.07 4.08 4.09 4.10 4.11 4.12 Brukner. Clinical Sports Medicine. 4th Edition. McGraw-Hill. 2012

- ↑ Miozzari et al.. Effects of removal of the acetabular labrum in a sheep hip model. Osteoarthritis and cartilage 2004. 12:419-30. PMID: 15094141. DOI.

- ↑ [1]

- ↑ Cite error: Invalid

<ref>tag; no text was provided for refs namedYazbek - ↑ De Luigi et al.. Use of Platelet-Rich Plasma for the Treatment of Acetabular Labral Tear of the Hip: A Pilot Study. American journal of physical medicine & rehabilitation 2019. 98:1010-1017. PMID: 31162277. DOI.

- ↑ Rahl et al.. Outcomes After Arthroscopic Hip Labral Reconstruction: A Systematic Review and Meta-analysis. The American journal of sports medicine 2020. 48:1748-1755. PMID: 31634004. DOI.