Interspinous Oedema

(Redirected from Interspinous Bursitis)

Interspinous oedema is a finding seen on MRI and can be symptomatic or asymptomatic. This finding is typically seen in the lumbar spine, but also occurs in the cervical spine.

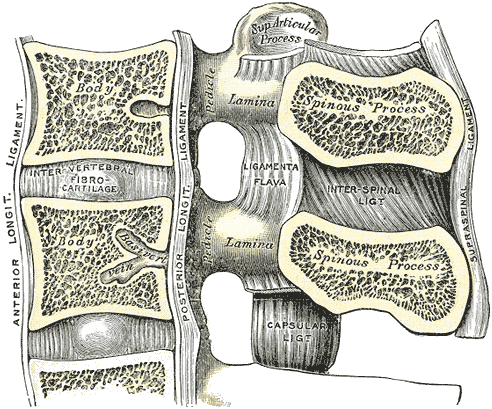

Anatomy

There are several soft tissue structures located in the posterior aspect of the lumbar spines. Namely, the multifidi muscles, interspinalis muscles, interspinous ligaments, and fat.

There are a variable number of bursal cavities located between the spinous processes of the cervical and lumbar segments in the interspinal ligaments. Bursal cavities are more common with increasing age, with L3/4 and L4/5 being most common. The interspinous ligament is thin centrally and undergoes fatty degeneration and cavitation in the sixth decade.[1]

Interspinous ligament

There are three parts to the interspinous ligaments. Ventrally there are fibres that run posterocranially from the dorsal aspect of the ligamentum flavum to the anterior half of the lower border of the upper spinous process. Dorsally there are fibres that run from the posterior half of the upper border of the lower spinous process and pass behind the posterior border of the upper spinous process. Viewed anteriorly but not posteriorly, there are two interspinous ligaments that are separated by fat. The interspinous ligaments provide little resistance to spinous process separation with forward flexion.

Supraspinous ligament

The supraspinous ligament is not a true ligament, but rather largely consists of tendinous fibres from the back muscles, and is only well developed at the upper lumbar levels. It terminates at L3 in 22%, L4 in 73%, bridges L4-5 in 5%, and is routinely absent at L5-S1.

The superficial layer is collagenous and thought to represent superficial fascial condensation, and anchors the skin to the thoracolumbar fascia. It provides little resistance to spinous process separation. The middle layer consists of intertwining fibres of the thoracolumbar fascia and the aponeurosis of longissimus thoracis. The deep layer consists of strong tendinous fibres from the aponeurosis of longissimus thoracis. The tendons aggregate in a parallel manner towards the spinous processes, creating the impression of a ligament.

At the caudal levels of L4 and L5 there are only oblique fibres of the thoracolumbar fascia that intersect over the spinous processes and fuse with the aponeurosis of the longissimus thoracic that attach to the spinous processes.[2]

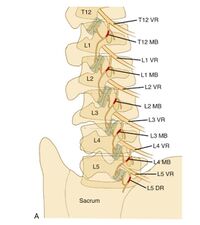

Innervation

All the above structures, as well as the periosteum of the spinous processes, are innervated by the medial branches of the lumbar dorsal rami, the same innervation as the facet joints.[2]

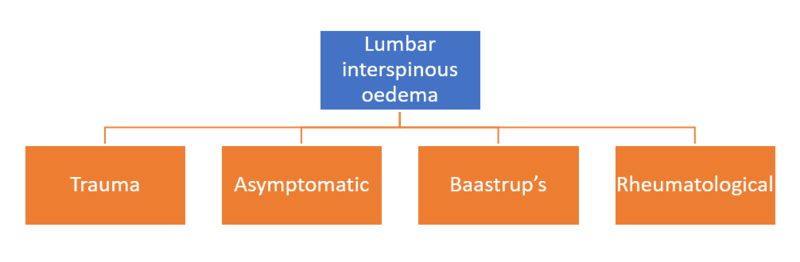

Aetiology

Interspinous oedema simply refers to a radiological finding, and does not presuppose any underlying cause. Bogduk theorises that the pain arises as a result of a periostitis of the spinous processes, or inflammation of the interspinous ligament, with nociception arising from the medial branches of the dorsal rami [2] Some authors use the term interspinous bursitis. The term bursitis, implying bursal pathology, is not able to be proven on imaging as the oedema could be from any number of causes. The term oedema is therefore preferred, although a bursal process is probably more likely in rheumatological cases. [3]

Interspinous oedema most commonly occurs in the mid and lower lumbar segments, and the finding increases in frequency with advancing age.[1]

Trauma

This may be the most common cause (see epidemiology section for audit data). It mostly occurs by lifting in flexion and occasionally in hyperextension. It can also occur with a fall.[4] The tissue injured is speculative but it is thought that the interspinous soft tissues are injured by compression between the bony spinous processes.[3]

Some authors believe that strain can result in changes to the interspinous ligaments, with rupture of the supraspinous and interspinous ligaments even occurring in some cases, most commonly in women aged between 15-35.[1] As outlined in the anatomy section, these ligaments do not provide significant resistance to forward flexion, but how that relates to the hypothetical concept of ligament strain remains to be seem.

Some possible mechanisms of injury:[3]

Injury in flexion when lifting, where there is eccentric load on the muscles. The multifidi cross several joints and that fits the usual mechanism of muscle sprain

- Reflex avlusion like a Jone's fracture of the base of the 5th metatarsal

- Sprain of the interspinous ligaments from excessive flexion

- Or a combination of the above

In a fall

- Sudden unguarded contraction of the interspinous muscles causing an avulsion

Asymptomatic/Incidental

Interspinous oedema can be an incidental finding, as evidenced by a negative response to a diagnostic local anaesthetic injection (see audit activity in epidemiology section).[4]

Baastrup's Disease

Baastrup's and the synonym kissing spines should be reserved for when there is evidence of spinous process impaction. It has traditionally been thought that Baastrup's is due to excessive lumbar lordosis, but this has been refuted in an MRI study.[5] However in this study, the authors used Baastrup's and interspinous oedema interchangeably, and did not differentiate between traumatic and atraumatic causes, nor did they differentiate whether there was lumbar spine impaction. In true Baastrup's the adjacent spinous processes, the most common level being L4/5, compress the intervening interspinous ligament. It is more common in the degenerative lumbar spine in those aged 70 and older, with no gender predilection. The changes occur in the context of disc height loss, spondylolisthesis, and spondylosis.[6][2] The clinical relevance of this entity is not clear and one study found that surgical excision of the spinous processes was only successful in 11 out of 64 patients.[7]

Rheumatological Conditions

Interspinous bursitis has been associated with several rheumatological conditions, especially polymyalgia rheumatica (47% of RA patients), but also rheumatoid arthritis (10%), and crystalopathies. Lumbar spine involvement is more common than cervical spine, even though neck pain is more common than low back pain. Overall the relationship with pain in these patients is not clear, but in a control group the findings were only seen in 1 out of 65 patients.[8][9]

Epidemiology

Useful data has been obtained from an audit of a Musculoskeletal Medicine Specialist's practice. The term symptomatic was denoted when there was evidence of lumbar interspinous oedema on MRI and significant improvement with a fluoroscopically guided injection. Of 178 new cases of low back pain +/- leg pain, there were 21 cases of symptomatic interspinous oedema (12% prevalence), 6 cases of asymptomatic interspinous oedema (3.3% prevalence), and 10 inconclusive cases (5.6% prevalence).[4]

An MRI study using of 539 patients with back or leg pain found lumbar interspinous oedema to be present in 8.2% of cases. When present, it was seen at multiple levels in 47.7%; 71.4% of these cases had two levels involved, and 28.6% had 3 levels involved. The machine was 1.5 Tesla, fat suppression was not routinely used, and coronal sequences were not obtained. There was no control group, and no correlation with diagnostic blocks. The authors found an association with anterolisthesis and central spinal canal stenosis, and theorised that "bursitis" may develop due to translational movements of the spinous processes abutting each other. There was no association with lordosis.[5]

Clinical Features

- See also: Case:Low Back Pain 002

Certain patterns have been found in the presentation of symptomatic interspinous oedema. The onset of pain is closely linked to the time of the accident/forces, and the patient is definite about the accident. The pain distribution is highly variable. The pain is significant, and affects sleep, work, and recreation. On examination there is tenderness of the interspinous soft tissues.[4]

In kissing spines, patients may have midline back pain that worsens with extension and relieved by flexion. On examination the patient may be tender over the suspected level. Rarely an epidural cystic mass may cause neurogenic claudication with extension.[6]

Imaging

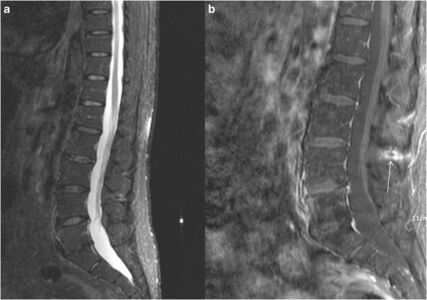

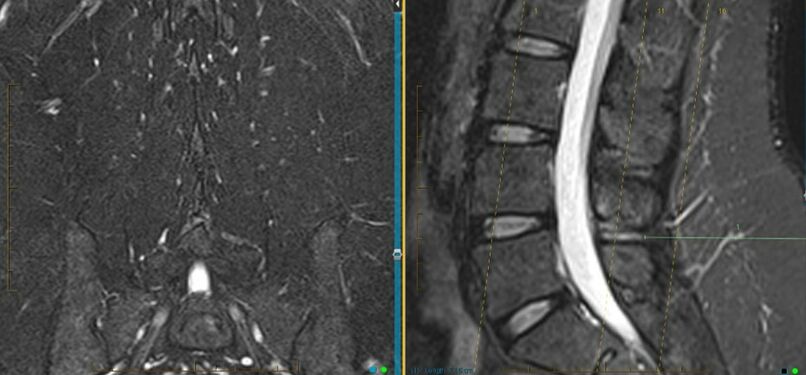

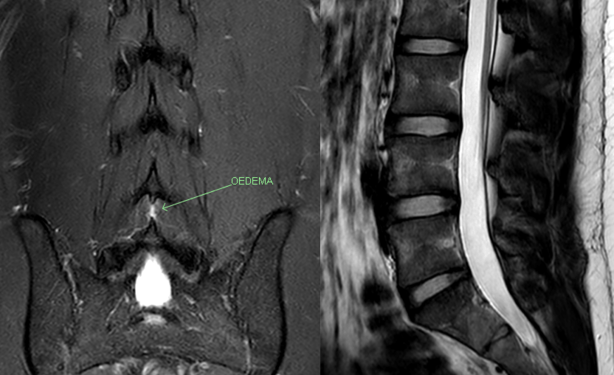

The diagnosis is supported by finding interspinous oedema on MRI. The two key sequences are the coronal fat sat Dixon and the T2 sagittal sequence. The coronal fat sat sequence needs to be specifically requested at certain radiology providers in New Zealand.

Diagnosis

In the appropriate clinical setting and imaging findings, the diagnosis can be confirmed by finding resolution of pain with a diagnostic injection of local anaesthetic under fluoroscopic guidance.[1][4] Injections at non-involve segments may theoretically confirm the clinical response.[1]

The interspinous soft tissues are supplied by the medial branches of the dorsal rami. Therefore medial branch diagnostic blocks would be positive, and radiofrequency neurotomy of the medial branches would relieve the pain. There is discussion amongst the Musculoskeletal Medicine community as to whether, if the history fits, should symptomatic interspinous oedema be excluded by the appropriate MRI sequences before embarking on MBBs?[4]

Differential Diagnosis

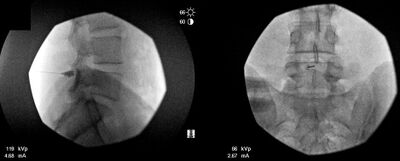

Baastrup's disease, first described in 1933, is thought to be rare. Imaging includes radiography, CT, and MRI. The hallmark finding suggestive of Baastrup's is close approximation and contact of adjacent spinous processes along with oedema, cystic lesions, sclerosis, flattening and enlargement of the articulating surfaces of the two affected spinous processes, bursitis and occasionally epidural cysts or midline epidural fibrotic masses. Usually generalised degenerative spinal changes are seen, most prominent at the affected level, including facet joint hypertrophy, disc herniation, and spondylolisthesis. On MRI gadolinium administration may show enhancement of the affected area.[6]

MRI, STIR sequence, sagittal reconstruction illustrating bone oedema at both the spinous processes of L3-L4 level.[6]

Lumbar spine X-ray, AP (left image) and lateral (right image) views illustrating close approximation and contact of spinous processes at L4-L5 level with sclerosis and flattening of the articulating surfaces (white arrow).[6]

In rheumatological cases, interspinous oedema is likely to be incidental, rather than related to any pain, and the patient is likely to have already been diagnosed or there will be other features to make the diagnosis of an inflammatory condition.

There may be additional factors in the patients pain such as facet joint irritation or disc pain which may need to be addressed.

Treatment

In most cases symptoms can be treated with conservative management and corticosteroid injection. Surgery is not indicated.

Injections are performed at the level of the interspinous ligament and have been used with good therapeutic benefit.[1] There is usually durable fast relief by an interspinous injection of steroid and local anaesthetic. This should ideally be done with imaging guidance to ensure accurate needle positioning. In New Zealand, fluoroscopic guidance is normally used.[4] Ultrasound could theoretically be used as an alternative, however this has not been studied.

The fluoroscopic technique is as follows:[4]

- Advance a 9 cm 22-gauge spinal needle into the interspinous space using AP and lateral projections.

- Infiltrated 1 mL Omnipaque 300 into the interspinous space to ensure position.

- Infiltrate a mixture of 40 mg Kenacort A and 0.5 mL 0.75% Ropivacaine into the affected interspinous space.

Resources

- The case report by DePalma has useful discussion and literature review.[1]

- An open access review of Baastrup's is available by Filippiadis et al.[6]

Summary

- Interspinous oedema can be asymptomatic, but is more common in symptomatic patients.[Level 5]

- The symptomatic patient is definite about an accident with the pain being closely linked to the inciting event. The pain distribution is quite variable, but the pain intensity is often severe with marked effects on function. There is tenderness in the affected interspinous space.[Level 5]

- For diagnosis the MRI needs to include a coronal T2 fat sat Dixon sequence, and the diagnosis is supported by abolition of pain with image guided injection.[Level 5]

- If looking at doing medial branch blocks, consider first excluding the presence of interspinous oedema on MRI.[Level 5]

- There is usually durable fast relief by an interspinous injection of steroid and LA. [Level 5]

References

- ↑ 1.0 1.1 1.2 1.3 1.4 1.5 1.6 DePalma et al.. Interspinous bursitis in an athlete. The Journal of bone and joint surgery. British volume 2004. 86:1062-4. PMID: 15446539. DOI.

- ↑ 2.0 2.1 2.2 2.3 Bogduk, Nikolai. Clinical and radiological anatomy of the lumbar spine. Chapter 15. Edinburgh: Elsevier/Churchill Livingstone, 2012.

- ↑ 3.0 3.1 3.2 Correspondence with Dr Mike Cleary, Musculoskeletal Medicine Physician

- ↑ 4.0 4.1 4.2 4.3 4.4 4.5 4.6 4.7 Dr Mike Cleary. Diagnosing and Treating Symptomatic Traumatic Lumbar Interspinous Oedema (LISO). 2021 Queenstown Retreat.

- ↑ 5.0 5.1 Maes et al.. Lumbar interspinous bursitis (Baastrup disease) in a symptomatic population: prevalence on magnetic resonance imaging. Spine 2008. 33:E211-5. PMID: 18379391. DOI.

- ↑ 6.0 6.1 6.2 6.3 6.4 6.5 Filippiadis et al.. Baastrup's disease (kissing spines syndrome): a pictorial review. Insights into imaging 2015. 6:123-8. PMID: 25582088. DOI. Full Text.

- ↑ Beks. Kissing spines: fact or fancy?. Acta neurochirurgica 1989. 100:134-5. PMID: 2589119. DOI.

- ↑ Salvarani et al.. Cervical interspinous bursitis in active polymyalgia rheumatica. Annals of the rheumatic diseases 2008. 67:758-61. PMID: 18208867. DOI.

- ↑ Camellino et al.. Interspinous bursitis is common in polymyalgia rheumatica, but is not associated with spinal pain. Arthritis research & therapy 2014. 16:492. PMID: 25435011. DOI. Full Text.

Literature Review

- Reviews from the last 7 years: review articles, free review articles, systematic reviews, meta-analyses, NCBI Bookshelf

- Articles from all years: PubMed search, Google Scholar search.

- TRIP Database: clinical publications about evidence-based medicine.

- Other Wikis: Radiopaedia, Wikipedia Search, Wikipedia I Feel Lucky, Orthobullets,

![MRI, STIR sequence, sagittal reconstruction illustrating bone oedema at both the spinous processes of L3-L4 level.[6]](/w/img_auth.php/thumb/8/8d/Baastrup_kissing_spine_bone_oedema_MRI.jpg/301px-Baastrup_kissing_spine_bone_oedema_MRI.jpg)

![Lumbar spine X-ray, AP (left image) and lateral (right image) views illustrating close approximation and contact of spinous processes at L4-L5 level with sclerosis and flattening of the articulating surfaces (white arrow).[6]](/w/img_auth.php/thumb/f/f5/Baastrup_kissing_spine_XR.jpg/498px-Baastrup_kissing_spine_XR.jpg)