Lumbar Spine Arthrodesis

Lumbar spine arthrodesis is surgical procedure that is typically performed to address degenerative conditions with mechanical instability, such as spondylolisthesis or adult scoliosis. There are multiple surgical approaches available to achieve fusion in the lumbar spine, including posterior, anterior, and lateral approaches. The choice of approach depends on factors such as the level of spinal fusion, the number of fusion levels required, spinal alignment, and the possibility of concurrent autograft harvest.

Approaches

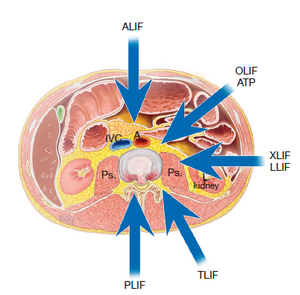

The posterior approach is the most commonly performed technique for lumbar spinal fusion, involving the fusion bed typically through the facet joints and intertransverse gutters. This approach can be supplemented with posterior pedicle screw instrumentation, and intervertebral disc space may be accessed for interbody fusion via posterior lumbar interbody fusion (PLIF) or transforaminal lumbar interbody fusion (TLIF) techniques. Disadvantages of the posterior approach include pain from dissection and retraction of paraspinal muscles, potential for nerve root injury, limited surface area for fusion, and limited ability to correct sagittal alignment without additional osteotomy.

The anterior lumbar interbody fusion approach (ALIF), performed in the supine position with retroperitoneal dissection, allows access to the intervertebral discs of the mid to lower lumbar spine. The greatest surgical risk with this approach is vascular, requiring ligation of the iliolumbar vein for safe retraction of the aorta and inferior vena cava. The cephalad limit to anterior access is frequently the L3–4 disc space.

The lateral approach has gained popularity due to its relative technical ease and ability to address multiple levels. This approach is well-tolerated by patients and provides correction in the coronal plane for scoliotic deformities. There are variations in surgical approach based on the relation to the psoas muscle, such as the transpsoas approach (lateral lumbar interbody fusion [LLIF], extreme lateral interbody fusion [XLIF]) and the anterior to psoas approach (oblique lateral interbody fusion [OLIF]). The transpsoas approach may have a higher rate of nerve injury, while the anterior to psoas approach allows access to more caudal levels but has a greater potential for vascular injury.

Complications

Complications specific to this procedure include pseudoarthrosis, graft subsidence, and hardware loosening/migration/fracture.

Fusion rates for lumbar spine arthrodesis are dependent on the presence of instrumentation and surgical approach. Zdeblick reported a 65% success rate without instrumentation, increasing to 77% with semirigid instrumentation and 95% with rigid instrumentation.[1] Christensen et al demonstrated an 80% fusion rate with posterolateral arthrodesis with instrumentation for degenerative lumbar disease and a 92% fusion rate with the addition of ALIF.[2] More recent studies have shown successful arthrodesis in 84 to 92% for posterior lumbar fusion with rigid instrumentation.[3] The addition of anterior, transforaminal, or posterior interbody techniques to rigid fixation increases fusion rates to 88 to 100%, with similar fusion rates regardless of the approach.[4]

References

- ↑ Zdeblick, T. A. (1993-06-15). "A prospective, randomized study of lumbar fusion. Preliminary results". Spine. 18 (8): 983–991. doi:10.1097/00007632-199306150-00006. ISSN 0362-2436. PMID 8367786.

- ↑ Christensen, Finn B.; Hansen, Ebbe S.; Eiskjaer, Søren P.; Høy, Kristian; Helmig, Peter; Neumann, Pavel; Niedermann, Bent; Bünger, Cody E. (2002-12-01). "Circumferential lumbar spinal fusion with Brantigan cage versus posterolateral fusion with titanium Cotrel-Dubousset instrumentation: a prospective, randomized clinical study of 146 patients". Spine. 27 (23): 2674–2683. doi:10.1097/00007632-200212010-00006. ISSN 1528-1159. PMID 12461393.

- ↑ Chun, Danielle S.; Baker, Kevin C.; Hsu, Wellington K. (2015-10). "Lumbar pseudarthrosis: a review of current diagnosis and treatment". Neurosurgical Focus. 39 (4): E10. doi:10.3171/2015.7.FOCUS15292. ISSN 1092-0684. PMID 26424334. Check date values in:

|date=(help) - ↑ Teng, Ian; Han, Julian; Phan, Kevin; Mobbs, Ralph (2017-10). "A meta-analysis comparing ALIF, PLIF, TLIF and LLIF". Journal of Clinical Neuroscience: Official Journal of the Neurosurgical Society of Australasia. 44: 11–17. doi:10.1016/j.jocn.2017.06.013. ISSN 1532-2653. PMID 28676316. Check date values in:

|date=(help)