Neck-Tongue Syndrome: Difference between revisions

No edit summary |

No edit summary |

||

| Line 97: | Line 97: | ||

* C2 nerve corticosteroid injection | * C2 nerve corticosteroid injection | ||

* Atlanto-axial joint arthrodesis | * Atlanto-axial joint arthrodesis | ||

[[Category:Cervical Spine Conditions]] | [[Category:Cervical Spine Conditions]] | ||

{{References}} | {{References}} | ||

{{Reliable sources}} | {{Reliable sources}} | ||

Revision as of 22:29, 9 April 2022

| |

| Neck-Tongue Syndrome | |

|---|---|

| Definition | The sudden onset of occipital and/or upper neck pain brought out by sudden rotatory head movement and accompanied by abnormal sensation and/or posture of the ipsilateral tongue. |

| Epidemiology | Usually begins in childhood. Very rare. |

| Pathophysiology | Subluxation of the atlantoaxial joint resulting in compression of the C2 ventral ramus |

| Treatment | Supportive |

Neck-Tongue Syndrome is a rare condition characterised by brief attacks of neck and/or occipital pain with neck rotation associated with sensory changes of the ipsilateral half of the tongue.

Pathophysiology

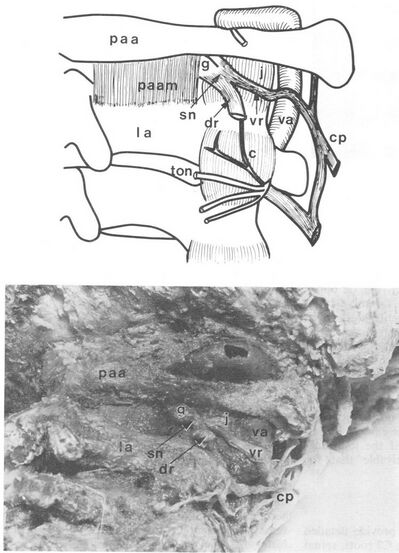

Top: Schematic illustrations of a dorsal view. Bottom: Dissection of a right dorsolateral view showing the C2 dorsal ramus cut at its point of branching (dr), cervical plexus (cp), third occipital nerve (ton), communicating branch C2 to C3 (c), and posterior atlantoaxial membrane (paam).

Copyright BMJ, reproduced with permission.[2]

Excessive rotation leads to subluxation of the lateral atlanto-axial joint leading to occipital pain. The C2 ventral ramus sits dorsal to the joint and is impinged against bone.

The symptoms can be explained as follows:[3]

Neck pain: The pain may come from joint capsule stretch.[3]

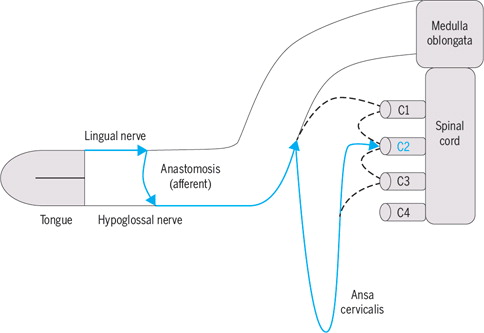

Tongue symptoms: The lingual afferents (trigeminal origin) from the tongue pass from the hypoglossal nerve into the C2 ventral ramus through the ansa cervicalis. C2 ventral ramus compression therefore causes tongue numbness. Most of the fibres are proprioceptive, and so patients may have pseudoathetosis of the tongue.[4] Bogduk contends that the numbness may not be true numbness but rather all due to proprioceptive loss and analogous to the sensory symptoms seen in Bell's palsy.[2]

Sensory symptoms in the neck: may come from compression of the C2 ventral ramus and/or tension of the C2 spinal nerve or roots.

Facial and Retro-auricular symptoms: The C2 ventral ramus innervates some of the posterior face and mastoid process and so some patients have symptoms in these regions.[2]

Upper extremity tingling: Unclear why some patients report this. It may be due to dura mater traction resulting in tension on the lower cervical nerve roots.[3]

Epidemiology and Risk Factors

Three quarters of patients have their onset in childhood or adolescence. There may be a family history which could relate to hypermobility. Previous trauma may be implicated. Patients may have another additional type of headache disorder other than Neck-Tongue Syndrome, especially migraine.[3]

A population based study in Norway found a prevalence of 0.2%.[5]

Clinical Features

- Onset in adulthood

- Post-traumatic onset

- Persistent symptoms

- Known rheumatic disease of the cervical spine

The symptoms; namely pain, numbness, and motor symptoms; of Neck-Tongue Syndrome are typically brief, in the order of seconds to minutes and are precipitated by sudden turning of the head.

The pain is in the C2 root distribution and is reproducible with neck rotation. Patients may report a popping or clicking sensation with the episodes.[3] There may be a decreased range of motion and tenderness of the upper cervical spine. [4]

There is associated numbness and/or paraesthesias of the ipsilateral half of the tongue with or without pseudoathetosis. There may be additional areas of sensory abnormalities in the neck and occiput.[3][4]

Diagnosis

Gelfand and colleagues proposed the following diagnostic criteria:[3]

Description. The sudden onset of occipital and/or upper neck pain brought out by sudden rotatory head movement and accompanied by abnormal sensation and/or posture of the ipsilateral tongue. The pain is usually severe in intensity.

| Criterion | Feature |

|---|---|

| A | At least two episodes that fulfill criteria B through E |

| B | Sharp or stabbing unilateral pain in the upper neck, or occipital region, or both, precipitated by sudden turning of the neck, with or without simultaneous dysaesthesia. |

| C | Concurrent abnormal sensation, or posture, or both, of the ipsilateral tongue |

| D | Duration from several seconds to several minutes |

| E | Not better accounted for by another ICHD-3 disorder |

Differential Diagnosis

Other causes of C2 ventral ramus compression are congenital fusion, stenosis, aneurysm, malignancy, or infection.

- Diseases of the eyes, ears, nose, throat, teeth

- Tumours of the hypopharynx (tonsillar fossa, piriform sinus)

- Cerebellopontine angle tumours

- Demyelinating disease

- Temporal arteritis

- Glossopharyngeal neuralgia

Investigations

Imaging: Imaging is usually normal. The instability of the atlanto-axial joint is in the transverse plane in extremes of range and so normal sequences are unlikely to pick up any abnormalities. Undertaking axial CT scanning or biplanar fluoroscopy is not recommended as routine because of the extreme range.[3]

Indications for imaging are the development of symptoms following trauma and the initial occurrence in adulthood. Reporting should be done by experienced neuroradiologists.[3]

Blood tests: Blood tests are done to investigate for infection, inflammation (temporal arteritis), and malignancy. Consider FBC, UEC, CRP, and ESR.[4]

Other: Endoscopy of the hypopharynx looking at the piriform sinuses can be done to rule out malignancy of that area.[4]

Treatment

Treatment is usually not required if the attacks are uncommon and brief.

- Immobilisation the cervical spine with a soft collar.

- NSAIDs.

- Manual therapy

- Home exercises

- C2 nerve corticosteroid injection

- Atlanto-axial joint arthrodesis

- ↑ Niethamer, Lisa; Myers, Robin (2016-03). "Manual Therapy and Exercise for a Patient With Neck-Tongue Syndrome: A Case Report". The Journal of Orthopaedic and Sports Physical Therapy. 46 (3): 217–224. doi:10.2519/jospt.2016.6195. ISSN 1938-1344. PMID 26868897. Check date values in:

|date=(help) - ↑ 2.0 2.1 2.2 Bogduk, N. (1981-03). "An anatomical basis for the neck-tongue syndrome". Journal of Neurology, Neurosurgery, and Psychiatry. 44 (3): 202–208. doi:10.1136/jnnp.44.3.202. ISSN 0022-3050. PMC 490891. PMID 7229642. Check date values in:

|date=(help)CS1 maint: PMC format (link) - ↑ 3.0 3.1 3.2 3.3 3.4 3.5 3.6 3.7 3.8 Gelfand, Amy A.; Johnson, Hannah; Lenaerts, Marc Ep; Litwin, Jessica R.; De Mesa, Charles; Bogduk, Nikolai; Goadsby, Peter J. (2018-02). "Neck-Tongue syndrome: A systematic review". Cephalalgia: An International Journal of Headache. 38 (2): 374–382. doi:10.1177/0333102416681570. ISSN 1468-2982. PMID 28100071. Check date values in:

|date=(help) - ↑ 4.0 4.1 4.2 4.3 4.4 Waldman, Steven D. Atlas of uncommon pain syndromes. Philadelphia, PA: Elsevier Inc, 2020.

- ↑ Sjaastad, O.; Bakketeig, L. S. (2006-03). "Neck-tongue syndrome and related (?) conditions". Cephalalgia: An International Journal of Headache. 26 (3): 233–240. doi:10.1111/j.1468-2982.2006.00926.x. ISSN 0333-1024. PMID 16472328. Check date values in:

|date=(help)

Literature Review

- Reviews from the last 7 years: review articles, free review articles, systematic reviews, meta-analyses, NCBI Bookshelf

- Articles from all years: PubMed search, Google Scholar search.

- TRIP Database: clinical publications about evidence-based medicine.

- Other Wikis: Radiopaedia, Wikipedia Search, Wikipedia I Feel Lucky, Orthobullets,