Obesity and Chronic Pain: Difference between revisions

No edit summary |

No edit summary |

||

| Line 84: | Line 84: | ||

<references/> | <references/> | ||

{{Reliable sources|synonym1=Obesity pain}} | {{Reliable sources|synonym1=Obesity pain}} | ||

[[Category:Widespread]] | [[Category:Widespread]] | ||

[[Category:Lifestyle]] | |||

Revision as of 16:09, 4 December 2022

Obesity is associated with lower limb and hand osteoarthritis, chronic pain, and disability.

Rates of Obesity

The rates of obesity have been increasing in New Zealand. In the New Zealand Health Survey 2020/2021, 34.3% of people over aged 15 were obese. This is an increase from 31.2% in 2019/2020. Similarly childhood obesity has also been increasing and was 12.7% in 2020/2021[1]

There are drastic differences between ethnicities. Obesity was found in 71.3% of Pacific, 50.8% of Maori, 31.9% of European/Other, and 18.5% of Asians. There was a 1.6 times higher rate of obesity in those living in socioeconomically deprived areas.[1]

Obesity and Chronic Pain Correlations

Several studies have found strong associations between obesity and chronic pain.

- A Danish population study found that chronic pain defined as greater than 6 months of duration was found in 22% of those with normal weight, 29% in overweight, and 40% in obesity.[3]

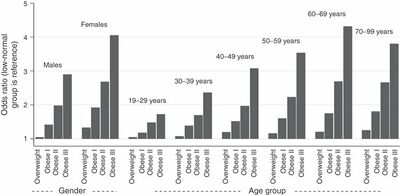

- A USA study looked pain experienced "yesterday," and this was reported in 19% of those with normal weight, 22% of those overweight (OR 1.7 - 3.5), and 28-44% of obese (OR 1.7 - 3.5).[2] (Figure 1)

- A CDC study found that doctor diagnosed arthritis was present in 16% of normal weight, 23% of overweight, and 31% of obese adults.[4]

- A USA survey of 6796 subjects found that low back pain was present in 3% of those with normal weight, 5% who are overweight, and 7-12% of those with obesity.[5]

- A UK study of 5752 GP patients found an odds ratio of 1.5 for overweight and 2.21 for obesity. Underweight also had an increased OR of 1.27. For intensity, disability, and chronicity 30% was attributed to abnormal BMI, 40% to deprivation, and 57% to the combined effects of BMI and deprivation.[6]

- The very large Norwegian HUNT study looked at subjects with no pain at baseline and followed them up over 10 years. Obesity was found to have odds ratios of 1.26-1.29 for arm pain, 1.2 for neck shoulder and back pain, 4.37 for knee pain in women, 2.78 for knee pain in men, 1.4 for hip pain (no clear association), and 1.79 for fibromyalgia. Exercising in the presence of obesity did alter the risk of osteoarthritis.[7]

There have also been a number of meta-analyses

- A meta-analysis of 33 studies found an odds ratio of 1.5 for obesity and low back pain.[8]

- A meta-analysis of 26 studies found an odds ratio of 1.4 for obesity and lumbar radicular pain. There was also increased rates of hospitalisation and surgery.[9]

Pathophysiology

There are several potential mechanisms for the pathophysiology of pain in obesity

- Direct mechanical effect on weightbearing joints such as the knees. For example each kilogram of weight loss results in 4 kilograms of less load on the knee per step.[10]

- Adipokines, leptin, and inflammatory proteins released by adipose tissue.

- Genetic clusters: depression, obesity, and chronic conditions with pain

- Poor general health

- Reduced physical activity

- Psychosocial and environmental factors

Weight Loss Outcomes

Weight loss reduces both pain and disability in patients with knee osteoarthritis. For example, in the IDEA trial, an RCT of 399 overweight and obese adults with knee osteoarthritis, diet-induced weight loss of 10% or greater body weight plus physical exercise for 18 months was more effective than each intervention alone.[12] A meta-analysis of 19 RCTs in patients with knee or hip osteoarthritis found that weight reduction results in a small to moderate improvement in pain and function.[13]

Bariatric surgery may be effective in improving chronic pain. For example one study of 48 patients with mean post-surgical weight loss of 41 +/- 15kg found that musculoskeletal complaints reduced from 100% prevalence down to 23%.[14]

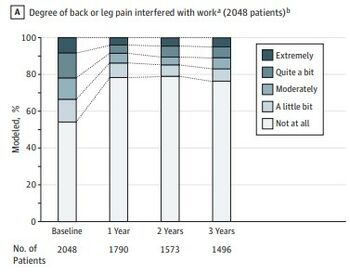

A study of 2048 patients with back and leg pain found that weight loss with bariatric surgery at one year resulted in 75% of patients having a clinically meaningful reduction in hip and knee symptoms, 50% had a reduction in bodily pain, and 75% had increased function. At three years 45% had reduced bodily pain and 70% had increased function.[11] (Figure 2)

Another study of 2862 patients found that bariatric surgery resulted in 80% reporting improvement in hip pain, and 75% reporting improvement in knee pain. The effect was greatest in those with moderate to severe symptoms.[15] (Table 1)

| Hip Baseline | Hip One Year Post-op | Knee Baseline | Knee One Year Post-op | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| No Symptoms | 42.4% | 73.8% | 15.4% | 62% |

| Mild Symptoms | 23.2% | 15.8% | 26.7% | 24.6% |

| Moderate Symptoms | 21.5% | 7.5% | 29.3% | 9% |

| Intense Symptoms | 12.9% | 2.9% | 28.5% | 4.4% |

See Also

References

- ↑ 1.0 1.1 Obesity statistics | Ministry of Health NZ

- ↑ 2.0 2.1 Stone AA, Broderick JE. Obesity and pain are associated in the United States. Obesity (Silver Spring). 2012 Jul;20(7):1491-5. doi: 10.1038/oby.2011.397. Epub 2012 Jan 19. Erratum in: Obesity (Silver Spring). 2012 Jul;20(7):1546. PMID: 22262163.

- ↑ Dansie EJ, Turk DC, Martin KR, Van Domelen DR, Patel KV. Association of chronic widespread pain with objectively measured physical activity in adults: findings from the National Health and Nutrition Examination survey. J Pain. 2014 May;15(5):507-15. doi: 10.1016/j.jpain.2014.01.489. Epub 2014 Jan 23. PMID: 24462501.

- ↑ US Department of Health and Human Services. National center for chronic disease prevention and health promotion division of adult and community health. https://www.cdc.gov/arthritis/data_statistics/arthritis-related-stats.htm

- ↑ Smuck M, Kao MC, Brar N, et al. Does physical activity influence the relationship between low back pain and obesity? The Spine Journal : Official Journal of the North American Spine Society. 2014 Feb;14(2):209-216. DOI: 10.1016/j.spinee.2013.11.010. PMID: 24239800.

- ↑ Webb R, Brammah T, Lunt M, Urwin M, Allison T, Symmons D. Prevalence and predictors of intense, chronic, and disabling neck and back pain in the UK general population. Spine (Phila Pa 1976). 2003 Jun 1;28(11):1195-202. doi: 10.1097/01.BRS.0000067430.49169.01. PMID: 12782992.

- ↑ Mork PJ, Holtermann A, Nilsen TI. Effect of body mass index and physical exercise on risk of knee and hip osteoarthritis: longitudinal data from the Norwegian HUNT Study. J Epidemiol Community Health. 2012 Aug;66(8):678-83. doi: 10.1136/jech-2011-200834. Epub 2012 Apr 17. PMID: 22511797.

- ↑ Shiri R, Karppinen J, Leino-Arjas P, Solovieva S, Viikari-Juntura E. The association between obesity and low back pain: a meta-analysis. Am J Epidemiol. 2010 Jan 15;171(2):135-54. doi: 10.1093/aje/kwp356. Epub 2009 Dec 11. PMID: 20007994.

- ↑ Shiri R, Lallukka T, Karppinen J, Viikari-Juntura E. Obesity as a risk factor for sciatica: a meta-analysis. Am J Epidemiol. 2014 Apr 15;179(8):929-37. doi: 10.1093/aje/kwu007. Epub 2014 Feb 24. PMID: 24569641.

- ↑ Messier SP, Gutekunst DJ, Davis C, DeVita P. Weight loss reduces knee-joint loads in overweight and obese older adults with knee osteoarthritis. Arthritis Rheum. 2005 Jul;52(7):2026-32. doi: 10.1002/art.21139. PMID: 15986358.

- ↑ 11.0 11.1 From King WC, Chen JY, Belle SH, Courcoulas AP, Dakin GF, Elder KA, Flum DR, Hinojosa MW, Mitchell JE, Pories WJ, Wolfe BM, Yanovski SZ. Change in Pain and Physical Function Following Bariatric Surgery for Severe Obesity. JAMA. 2016 Apr 5;315(13):1362-71. doi: 10.1001/jama.2016.3010. PMID: 27046364; PMCID: PMC4856477.

- ↑ Messier SP, Mihalko SL, Legault C, Miller GD, Nicklas BJ, DeVita P, Beavers DP, Hunter DJ, Lyles MF, Eckstein F, Williamson JD, Carr JJ, Guermazi A, Loeser RF. Effects of intensive diet and exercise on knee joint loads, inflammation, and clinical outcomes among overweight and obese adults with knee osteoarthritis: the IDEA randomized clinical trial. JAMA. 2013 Sep 25;310(12):1263-73. doi: 10.1001/jama.2013.277669. PMID: 24065013; PMCID: PMC4450354.

- ↑ Robson EK, Hodder RK, Kamper SJ, O'Brien KM, Williams A, Lee H, Wolfenden L, Yoong S, Wiggers J, Barnett C, Williams CM. Effectiveness of Weight-Loss Interventions for Reducing Pain and Disability in People With Common Musculoskeletal Disorders: A Systematic Review With Meta-Analysis. J Orthop Sports Phys Ther. 2020 Jun;50(6):319-333. doi: 10.2519/jospt.2020.9041. Epub 2020 Apr 9. PMID: 32272032.

- ↑ Hooper MM, Stellato TA, Hallowell PT, Seitz BA, Moskowitz RW. Musculoskeletal findings in obese subjects before and after weight loss following bariatric surgery. Int J Obes (Lond). 2007 Jan;31(1):114-20. doi: 10.1038/sj.ijo.0803349. Epub 2006 Apr 25. PMID: 16652131.

- ↑ 15.0 15.1 Birn I, Mechlenburg I, Liljensøe A, Soballe K, Larsen JF. The Association Between Preoperative Symptoms of Obesity in Knee and Hip Joints and the Change in Quality of Life After Laparoscopic Roux-en-Y Gastric Bypass. Obes Surg. 2016 May;26(5):950-6. doi: 10.1007/s11695-015-1845-x. PMID: 26306602.

Literature Review

- Reviews from the last 7 years: review articles, free review articles, systematic reviews, meta-analyses, NCBI Bookshelf

- Articles from all years: PubMed search, Google Scholar search.

- TRIP Database: clinical publications about evidence-based medicine.

- Other Wikis: Radiopaedia, Wikipedia Search, Wikipedia I Feel Lucky, Orthobullets,