Slipping Rib Syndrome

| |

| Slipping Rib Syndrome | |

|---|---|

| Epidemiology | Any age, females > males |

| Pathophysiology | loss of fibrous or cartilaginous attachments between ribs 8-10 causing subluxation and intercostal nerve impingement. |

| Risk Factors | hypermobility |

| History | Lower rib cage pain |

| Examination | Palpable separation of ≥1cm at insertion of any 8-10th rib cartilages, rib hypermobility, separation point tenderness. |

| Diagnosis | Can usually be diagnosed on history and exam |

| Tests | Dynamic ultrasound |

| Treatment | Nerve blocks, manipulation, topical analgesia, rib excision, Hansen repair |

| Prognosis | May have dramatic improvement with treatment |

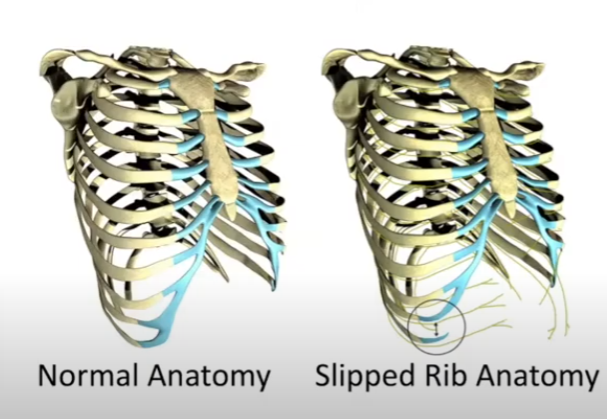

Slipped rib syndrome is a poorly understood, but potentially under-recognised cause for chronic chest wall pain. The pain arises when a lower anterior rib (usually rib 10, but occasionally rib 8 or 9) subluxes and causes pain due to impingement of the intercostal nerves.

Anatomy

- Main article: Ribs

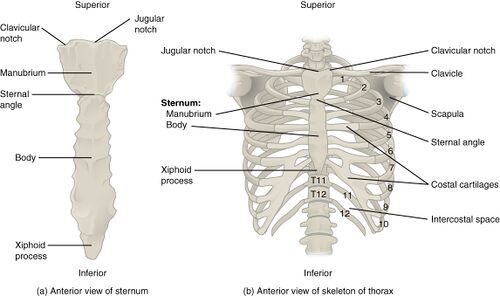

The true ribs are ribs 1-7 and have direct cartilaginous attachments to the sternum.

Ribs 8-10 are the false ribs are joined together anteriorly through a cartilaginous cap or fibrous band, called the interchondral joints. The interchondral joints normally merge into a common arch joining to the sternum. The false ribs "piggyback" on the 7th true rib cartilage. The interchondral joints provide some stability and flexibility with movement and breathing. The diaphragm connects to the false ribs, using them as an anchor point for activation.[1]

Ribs 11-12 are floating and do not have an attachment to the other cartilages or sternum.

Innervation of the intercostal nerves and visceral sympathetic nerves converge at the same spinal cord levels as slipping ribs, specifically over the eighth and ninth ribs. This can cause slipping pain to mimic pain from intra-abdominal pathology.[2]

Epidemiology

The diagnosis has been documented in 1% of all general medical referrals, and 5% of new gastroenterology referrals.[1] In research by Hansen et al, the mean age was 51 (it can occur in any age group), 90% were female, 38% have a history of trauma, the average duration of pain was 38 months. The patients tended to be at the end of the line with 41% had suicidal ideations due to pain severity.[3] In research by Foley of 362 athletes with rib pain, 54 were diagnosed with slipping rib syndrome. 70% were female, mean age was 19 years, 72% had insidious onset of pain, 90% had unilateral symptoms, the 10th rib was the most symptomatic at 44%, 8th and 9th ribs were 31% each.[2]

Aetiopathophysiology

The condition occurs when the costal cartilages of the false ribs (8-10) lose their fibrous or cartilaginous attachments to each other. One of the ribs is then able to sublux either superiorly or inferiorly with movement contacting or sliding beneath an adjacent rib. This causes irritation of the intercostal nerve between the two ribs. Impingement can occur with simple every day movements, and can cause chronic pain. The cartilagenous tips or fibrous attachments must be disrupted in order for these ribs to move. It most commonly involves the 10th rib, but can involve additional ribs. Slipping of ribs 11 or 12 can occur but is less common.[4]

Damage to the cartilage can occur due to trauma, degenerative change, and hypermobile connective tissue disorders.[4] The athletic population are at particular risk due to increased chest wall movement and increased risk of direct trauma.[2]

Clinical Manifestations

History

The pain is intermittent, usually severe, and is usually over the lower rib cage. The initial pain is sharp and stabbing that lasts a few minutes, with a secondary aching or burning pain that lasts several hours.[4] The pain is dermatomal, and typically extends to the back over the costovertebral joint. It can also refer to the upper abdomen. It can be confused with visceral pathology.[1] It can cause nausea or vomiting when severe which can further confuse matters.[4]

It often occurs with movement such as twisting, bending, deep breathing, sitting, sneezing, or coughing. There may be a popping or grinding sensation and they may be able to demonstrate the rib subluxing.[4]

There may or may not be a history of trauma - sudden extension or flexion, vigorous swimming, or repeated one-sided exercise such as one-sided weight bearing, ball throwing, or bat swinging.[4]

Some patients have temporary relief with stretching of the affected side or putting pressure over the area. Patients often report needing to rest for prolonged periods until the pain eases. Bilateral symptoms can occur but usually there is one dominant side.[4]

A common theme in case reports is significant delay to diagnosis and misdiagnosis, and even incorrectly labelling of the patient's pain being psychosomatic.[4]

Physical examination

Dr Hansen uses the following criteria for diagnosis on physical examination[1]

- Palpable separation of ≥1cm at insertion of any 8-10th rib onto the costal arch

- Same rib hypermobile on palpation

- Palpation at the separation point reproduces the patient's pain

The above is less painful than the traditional hook manoeuvre which is where the examiner slides their fingers under the costal margin lifting it anteriorly and superiorly looking for movement and pain.

Imaging

The condition can be assessed via dynamic ultrasound.[5][6] This involves visualising the cartilage with certain movements looking for the ribs moving under or abutting each other during. Visualisation during a crunch manoeuvre and pushing along the cartilages may be sufficient for diagnosis with a sensitivity of 92% and specificity of 100% in one study.[4]

This type of imaging assessment does not seem to be taught to MSK Sonographers in New Zealand at the time of writing, and so the study quality is likely to be variable.

Diagnosis

History and examination findings are often sufficient for diagnosis. A local anaesthetic intercostal nerve block can be used to further confirm the diagnosis and define the level of nerve irritation.[4]

Differential Diagnosis

- Somatic referred or radicular pain from the thoracic spine

- Abdominal wall strain or abdominal cutaneous nerve entrapment

- Intercostal neuritis

- Hepatobiliary or splenic disease

- Dyspepsia or oesophagitis

- Pancreatitis

- Renal colic

- Rib fracture

- Costochondritis and Tieze syndrome

- Lung pathology

Treatment

Reassurance that it is a benign condition is the first line treatment and this may be all that is required. Demonstrating to the patient the slipping rib through dynamic ultrasound imaging may provide additional reassurance. While surgery may be required, there have been reports of long lasting results with repeated nerve blocks, manipulative techniques, acupuncture, and topical analgesics.[4] In foley's study of 54 patients, the most successful treatment options included osteopathic manipulative treatment (71%), surgical resection (70%), and diclofenac gel (60%).[2]

Injections

Intercostal nerve blocks can provide symptom relief, but often only lasts up to 2-3 weeks, and the rebound pain can be severe in some cases. It is recommended to block the entire nerve as well as the two adjacent nerves. This is a reasonable starting point if conservative management has failed.

Surgery

Rib excision is the traditional technique but is associated with some morbidity. A new less invasive technique known as Hansen repair has been described[3] See a video of the technique here, and a webinar by Dr Hansen here. Vertical rib plating has also been described.[7]

Videos

References

- ↑ 1.0 1.1 1.2 1.3 1.4 https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=EZDFe3fC6ck

- ↑ 2.0 2.1 2.2 2.3 Foley et al.. Diagnosis and Treatment of Slipping Rib Syndrome. Clinical journal of sport medicine : official journal of the Canadian Academy of Sport Medicine 2019. 29:18-23. PMID: 29023277. DOI.

- ↑ 3.0 3.1 Hansen et al.. Minimally Invasive Repair of Adult Slipped Rib Syndrome Without Costal Cartilage Excision. The Annals of thoracic surgery 2020. 110:1030-1035. PMID: 32330472. DOI.

- ↑ 4.00 4.01 4.02 4.03 4.04 4.05 4.06 4.07 4.08 4.09 4.10 McMahon. Slipping Rib Syndrome: A review of evaluation, diagnosis and treatment. Seminars in pediatric surgery 2018. 27:183-188. PMID: 30078490. DOI.

- ↑ Meuwly et al.. Slipping rib syndrome: a place for sonography in the diagnosis of a frequently overlooked cause of abdominal or low thoracic pain. Journal of ultrasound in medicine : official journal of the American Institute of Ultrasound in Medicine 2002. 21:339-43. PMID: 11883545. DOI.

- ↑ Van Tassel et al.. Dynamic ultrasound in the evaluation of patients with suspected slipping rib syndrome. Skeletal radiology 2019. 48:741-751. PMID: 30612161. DOI.

- ↑ McMahon et al.. Vertical rib plating for the treatment of slipping rib syndrome. Journal of pediatric surgery 2020. . PMID: 33127061. DOI.

Literature Review

- Reviews from the last 7 years: review articles, free review articles, systematic reviews, meta-analyses, NCBI Bookshelf

- Articles from all years: PubMed search, Google Scholar search.

- TRIP Database: clinical publications about evidence-based medicine.

- Other Wikis: Radiopaedia, Wikipedia Search, Wikipedia I Feel Lucky, Orthobullets,