Smoking and Chronic Pain: Difference between revisions

(Created page with "The rate of smoking in those with chronic pain is higher than the general population at around 28% in one US study (no NZ data found). Smokers have higher pain intensities, nu...") |

No edit summary |

||

| Line 1: | Line 1: | ||

The rate of smoking in those with chronic pain is higher than the general population at around 28% in one US study (no NZ data found). Smokers have higher pain intensities, number of painful areas, levels of disability, and [[Opioid Deprescribing|opioid]] use to nonsmokers. <ref name=":0">{{Cite journal|last=Orhurhu|first=Vwaire J.|last2=Pittelkow|first2=Thomas P.|last3=Hooten|first3=W. Michael|date=2015|title=Prevalence of smoking in adults with chronic pain|url=https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/26185492|journal=Tobacco Induced Diseases|volume=13|issue=1|pages=17|doi=10.1186/s12971-015-0042-y|issn=2070-7266|pmc=4504349|pmid=26185492}}</ref> | The rate of smoking in those with chronic pain is higher than the general population at around 28% in one US study (no NZ data found).<ref name=":0" /> In the short term smoking is an analgesic, however in the long-term it is deleterious for pain as it exacerbates nociceptive, neuropathic, and psychosocial pain.<ref name=":1">{{Cite journal|last=Iida|first=Hiroki|last2=Yamaguchi|first2=Shigeki|last3=Goyagi|first3=Toru|last4=Sugiyama|first4=Yoko|last5=Taniguchi|first5=Chie|last6=Matsubara|first6=Takako|last7=Yamada|first7=Naoto|last8=Yonekura|first8=Hiroshi|last9=Iida|first9=Mami|date=2022-12|title=Consensus statement on smoking cessation in patients with pain|url=https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/36069935|journal=Journal of Anesthesia|volume=36|issue=6|pages=671–687|doi=10.1007/s00540-022-03097-w|issn=1438-8359|pmc=9666296|pmid=36069935}}</ref> Smokers have higher pain intensities, number of painful areas, levels of disability, and [[Opioid Deprescribing|opioid]] use to nonsmokers. <ref name=":0">{{Cite journal|last=Orhurhu|first=Vwaire J.|last2=Pittelkow|first2=Thomas P.|last3=Hooten|first3=W. Michael|date=2015|title=Prevalence of smoking in adults with chronic pain|url=https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/26185492|journal=Tobacco Induced Diseases|volume=13|issue=1|pages=17|doi=10.1186/s12971-015-0042-y|issn=2070-7266|pmc=4504349|pmid=26185492}}</ref> | ||

== Pathophysiology == | |||

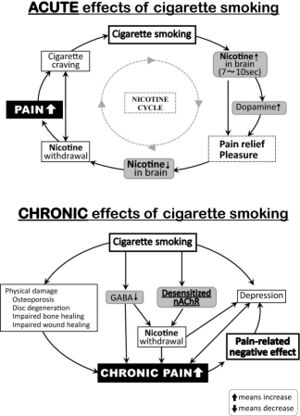

[[File:Smoking pathophysiology pain.jpg|thumb|The acute and chronic effects of cigarette smoking.<ref name=":1" />]] | |||

Tobacco smoke contains nicotine and over 4000 other compounds. Nicotine plays a role in pain-related pathophysiology. | |||

Nicotine binds to nicotinic acetylcholine receptors (nAChRs) which are found throughout the central and peripheral nervous systems and are involved in the physiology of arousal, sleep, anxiety, cognition, and pain. | |||

Cigarette smoking results in increased brain concentrations of nicotine within 7-10 seconds. It binds to nAChRs in the midbrain as well as in the peripheral nervous system. nAChR activation results in the release of noradrenaline, endogenous opioids, dopamine, and other neurotransmitters. This results in the feelings of euphoria and analgesia. The analgesic effect is from activation of the descending pain modulatory pathways and inhibition of afferent input to the dorsal horn.<ref name=":1" /> | |||

A meta-analysis for intranasal or transdermal nicotine found a small beneficial analgesic effect when used in the short-term for post-operative pain.<ref>{{Cite journal|last=Matthews|first=Annette M.|last2=Fu|first2=Rongwei|last3=Dana|first3=Tracy|last4=Chou|first4=Roger|date=2016-01-12|title=Intranasal or transdermal nicotine for the treatment of postoperative pain|url=https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/26756459|journal=The Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews|volume=2016|issue=1|pages=CD009634|doi=10.1002/14651858.CD009634.pub2|issn=1469-493X|pmc=8729826|pmid=26756459}}</ref> | |||

However inhaled nicotine has a half-life of approximately 30 minutes. This leads to a rapid decrease in the levels of the above neurotransmitters. This then leads to increased withdrawal, greater pain intensity, and cravings. Increased pain sensitivity occurs because long term use of nicotine results in neuroplastic changes with nAChR desensitisation. The only way to overcome this would be to smoke constantly, which is not typically possible, and it would have other deleterious effects. | |||

Therefore with use in the longer term pain is worsened, and the short term analgesic effects are outweighed by increased pain sensitivity from nicotine withdrawal due to rapid brain elimination of nicotine. There may also be reduced endogenous opioid release and blunting of the hypothalamic-pituitary-adrenal axis during stress.<ref name=":1" /> For example in the surgical setting, smokers have a higher incidence of inadequate post-operative pain control than nonsmokers.<ref>{{Cite journal|last=Matthews|first=Annette M.|last2=Fu|first2=Rongwei|last3=Dana|first3=Tracy|last4=Chou|first4=Roger|date=2016-01-12|title=Intranasal or transdermal nicotine for the treatment of postoperative pain|url=https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/26756459|journal=The Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews|volume=2016|issue=1|pages=CD009634|doi=10.1002/14651858.CD009634.pub2|issn=1469-493X|pmc=8729826|pmid=26756459}}</ref> | |||

Furthermore smoking has other deleterious effects on the musculoskeletal system. It increases the risk of disc degeneration, fractures, delayed tissue healing, and osteoporosis. From a psychosocial perspective it can further intensify depressive symptoms and cause sleep disturbance. | |||

In rat models nicotine exposure results in improved pain thresholds after 1 to 3 weeks of exposure. However after 6 weeks of use pain thresholds are worsened. Chronic exposure leads to decreased pain thresholds in a neuropathic pain model following withdrawal.<ref name=":1" /> | |||

== Opioid Use == | == Opioid Use == | ||

Not only is opioid use more common in smokers compared to non-smokers, there is also an increased quantity of opioid use per individual. This association holds when controlling for confounding factors. It is also more difficult for smokers who use opioids to quite smoking. The analgesic effect of opioids is enhanced by supraspinal nicotinic acetylcholine receptors.<ref name=":0" /> | Not only is opioid use more common in smokers compared to non-smokers, there is also an increased quantity of opioid use per individual. This association holds when controlling for confounding factors. It is also more difficult for smokers who use opioids to quite smoking. The analgesic effect of opioids is enhanced by supraspinal nicotinic acetylcholine receptors.<ref name=":0" /> | ||

== Low Back Pain == | |||

Smoking is a risk factor for [[Chronic Low Back Pain|chronic low back pain]]. The prevalence of smoking in this group reported to be between 16-40%.<ref name=":0" /> One large cohort study of over 70 thousand Canadians found a clear relationship between smoking and chronic low back pain risk. The prevalence was 23.3% in daily smokers compared to 15.7% in non-smokers. The association was stronger amongst younger individuals and the effect was dose dependent.<ref>{{Cite journal|last=Alkherayf|first=Fahad|last2=Agbi|first2=Charles|date=2009-10-01|title=Cigarette smoking and chronic low back pain in the adult population|url=https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/19796577|journal=Clinical and Investigative Medicine. Medecine Clinique Et Experimentale|volume=32|issue=5|pages=E360–367|doi=10.25011/cim.v32i5.6924|issn=1488-2353|pmid=19796577}}</ref> | |||

== Fibromyalgia == | |||

The rate of smoking amongst patients with fibromyalgia is higher than the general population. For example one study of 1566 patients reported a smoking prevalence of 38.7% in those with fibromyalgia compared to 24.7% of patients without fibromyalgia.<ref>{{Cite journal|last=Goesling|first=Jenna|last2=Brummett|first2=Chad M.|last3=Meraj|first3=Taha S.|last4=Moser|first4=Stephanie E.|last5=Hassett|first5=Afton L.|last6=Ditre|first6=Joseph W.|date=2015-07|title=Associations Between Pain, Current Tobacco Smoking, Depression, and Fibromyalgia Status Among Treatment-Seeking Chronic Pain Patients|url=https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/25801019|journal=Pain Medicine (Malden, Mass.)|volume=16|issue=7|pages=1433–1442|doi=10.1111/pme.12747|issn=1526-4637|pmc=4765172|pmid=25801019}}</ref> | |||

== References == | |||

[[Category:Widespread]] | [[Category:Widespread]] | ||

[[Category:Miscellaneous]] | [[Category:Miscellaneous]] | ||

Revision as of 11:39, 4 December 2022

The rate of smoking in those with chronic pain is higher than the general population at around 28% in one US study (no NZ data found).[1] In the short term smoking is an analgesic, however in the long-term it is deleterious for pain as it exacerbates nociceptive, neuropathic, and psychosocial pain.[2] Smokers have higher pain intensities, number of painful areas, levels of disability, and opioid use to nonsmokers. [1]

Pathophysiology

Tobacco smoke contains nicotine and over 4000 other compounds. Nicotine plays a role in pain-related pathophysiology.

Nicotine binds to nicotinic acetylcholine receptors (nAChRs) which are found throughout the central and peripheral nervous systems and are involved in the physiology of arousal, sleep, anxiety, cognition, and pain.

Cigarette smoking results in increased brain concentrations of nicotine within 7-10 seconds. It binds to nAChRs in the midbrain as well as in the peripheral nervous system. nAChR activation results in the release of noradrenaline, endogenous opioids, dopamine, and other neurotransmitters. This results in the feelings of euphoria and analgesia. The analgesic effect is from activation of the descending pain modulatory pathways and inhibition of afferent input to the dorsal horn.[2]

A meta-analysis for intranasal or transdermal nicotine found a small beneficial analgesic effect when used in the short-term for post-operative pain.[3]

However inhaled nicotine has a half-life of approximately 30 minutes. This leads to a rapid decrease in the levels of the above neurotransmitters. This then leads to increased withdrawal, greater pain intensity, and cravings. Increased pain sensitivity occurs because long term use of nicotine results in neuroplastic changes with nAChR desensitisation. The only way to overcome this would be to smoke constantly, which is not typically possible, and it would have other deleterious effects.

Therefore with use in the longer term pain is worsened, and the short term analgesic effects are outweighed by increased pain sensitivity from nicotine withdrawal due to rapid brain elimination of nicotine. There may also be reduced endogenous opioid release and blunting of the hypothalamic-pituitary-adrenal axis during stress.[2] For example in the surgical setting, smokers have a higher incidence of inadequate post-operative pain control than nonsmokers.[4]

Furthermore smoking has other deleterious effects on the musculoskeletal system. It increases the risk of disc degeneration, fractures, delayed tissue healing, and osteoporosis. From a psychosocial perspective it can further intensify depressive symptoms and cause sleep disturbance.

In rat models nicotine exposure results in improved pain thresholds after 1 to 3 weeks of exposure. However after 6 weeks of use pain thresholds are worsened. Chronic exposure leads to decreased pain thresholds in a neuropathic pain model following withdrawal.[2]

Opioid Use

Not only is opioid use more common in smokers compared to non-smokers, there is also an increased quantity of opioid use per individual. This association holds when controlling for confounding factors. It is also more difficult for smokers who use opioids to quite smoking. The analgesic effect of opioids is enhanced by supraspinal nicotinic acetylcholine receptors.[1]

Low Back Pain

Smoking is a risk factor for chronic low back pain. The prevalence of smoking in this group reported to be between 16-40%.[1] One large cohort study of over 70 thousand Canadians found a clear relationship between smoking and chronic low back pain risk. The prevalence was 23.3% in daily smokers compared to 15.7% in non-smokers. The association was stronger amongst younger individuals and the effect was dose dependent.[5]

Fibromyalgia

The rate of smoking amongst patients with fibromyalgia is higher than the general population. For example one study of 1566 patients reported a smoking prevalence of 38.7% in those with fibromyalgia compared to 24.7% of patients without fibromyalgia.[6]

References

- ↑ 1.0 1.1 1.2 1.3 Orhurhu, Vwaire J.; Pittelkow, Thomas P.; Hooten, W. Michael (2015). "Prevalence of smoking in adults with chronic pain". Tobacco Induced Diseases. 13 (1): 17. doi:10.1186/s12971-015-0042-y. ISSN 2070-7266. PMC 4504349. PMID 26185492.

- ↑ 2.0 2.1 2.2 2.3 2.4 Iida, Hiroki; Yamaguchi, Shigeki; Goyagi, Toru; Sugiyama, Yoko; Taniguchi, Chie; Matsubara, Takako; Yamada, Naoto; Yonekura, Hiroshi; Iida, Mami (2022-12). "Consensus statement on smoking cessation in patients with pain". Journal of Anesthesia. 36 (6): 671–687. doi:10.1007/s00540-022-03097-w. ISSN 1438-8359. PMC 9666296. PMID 36069935. Check date values in:

|date=(help) - ↑ Matthews, Annette M.; Fu, Rongwei; Dana, Tracy; Chou, Roger (2016-01-12). "Intranasal or transdermal nicotine for the treatment of postoperative pain". The Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews. 2016 (1): CD009634. doi:10.1002/14651858.CD009634.pub2. ISSN 1469-493X. PMC 8729826. PMID 26756459.

- ↑ Matthews, Annette M.; Fu, Rongwei; Dana, Tracy; Chou, Roger (2016-01-12). "Intranasal or transdermal nicotine for the treatment of postoperative pain". The Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews. 2016 (1): CD009634. doi:10.1002/14651858.CD009634.pub2. ISSN 1469-493X. PMC 8729826. PMID 26756459.

- ↑ Alkherayf, Fahad; Agbi, Charles (2009-10-01). "Cigarette smoking and chronic low back pain in the adult population". Clinical and Investigative Medicine. Medecine Clinique Et Experimentale. 32 (5): E360–367. doi:10.25011/cim.v32i5.6924. ISSN 1488-2353. PMID 19796577.

- ↑ Goesling, Jenna; Brummett, Chad M.; Meraj, Taha S.; Moser, Stephanie E.; Hassett, Afton L.; Ditre, Joseph W. (2015-07). "Associations Between Pain, Current Tobacco Smoking, Depression, and Fibromyalgia Status Among Treatment-Seeking Chronic Pain Patients". Pain Medicine (Malden, Mass.). 16 (7): 1433–1442. doi:10.1111/pme.12747. ISSN 1526-4637. PMC 4765172. PMID 25801019. Check date values in:

|date=(help)