Superior Cluneal Nerve Entrapment

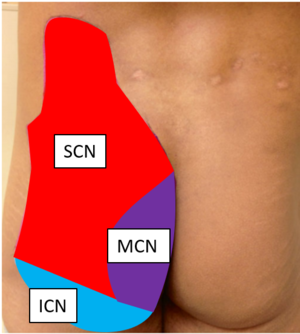

The cluneal nerves are a group of pure sensory nerves (superior, medial or middle, and inferior) that provide sensory supply to the buttocks. There is growing evidence that cluneal nerve entrapment, also known as cluneal neuralgia, or clunealgia, is an under-diagnosed cause of chronic low back and leg pain. Superior cluneal nerve (SCN) entrapment is thought to be more common than medial cluneal nerve (MCL) entrapment.

The best research paper on SCN entrapment that I have come across is a retrospective study by Kuniya et al who systematically evaluated 834 patients with CLBP; the article is open access and a highly recommended read. Their team has in general published a large amount of the recent literature on the topic.[1] A recent open access review article on SCN and MCN entrapment was authored by Isu et al.[2]

Anatomy

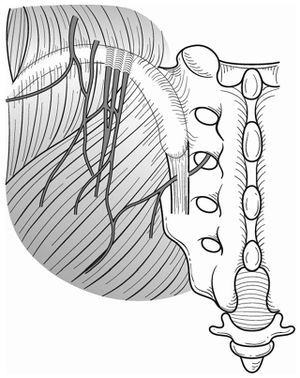

The cutaneous nerve supply of the upper back is supplied by the medial branches of the upper thoracic dorsal rami. The lower back meanwhile is supplied by the lateral branches of the lower thoracic and upper lumbar dorsal rami. The lateral branches of the lumbar dorsai rami are principally distributed to the iliocostalis lumborum muscle. The L1-L3 lateral branches can emerge from the dorsolateral border of the iliocostalis lumborum and become cutaneous, piercing the thoracolumbar fascia and descending inferolaterally across the iliac crest to innervate the skin of the buttock over an area extending from the iliac crest to the greater trochanter. When crossing the iliac crest they run parallel to one another with those from lower levels lying most medially. The lowest and most medial nerve that crosses the iliac crest does so approximately 7-8cm from the midline. There is variability in which of the lateral branches become cutaneous. In embryos and fetuses L1 is always cutaneous, L2 in 90%, L3 in 70%, and L4 in 40%. In adults it is similar except L4 cutaneous branches are uncommon. L1 exclusively in 60%. L1 and L2 in 27%. L1-L3 in 13%.[4]

- Superior cluneal nerves

The superior cluneal sensory nerves are thought to be composed of T11-L4 dorsal rami lateral branches. They travel caudally, crossing the PSIS, to the quadratus lumborum. The L1-3 nerves join, pass lateral to multifidus, and into the erector spinae muscles. The SCN passes through the psoas and paraspinal muscles, and pierces through the inferior latissimus dorsi. It supplies sensory innervation to the posterior iliac crest and superomedial gluteus maximus. There are three SCN branches: the lateral, middle, and medial branches across the PSIS. Do not confuse the middle and medial SCN branches with the MCN. The SCN often will pass through an osteofibrous tunnel made up of the thoracolumbar fascia and iliac crest.[5] There is significant anatomical variation. In a cadaver study of 109 medial branches, 39% passed through and osteofibrous tunnel, and of these only 5% exhibited obvious entrapment, or 2% of the total dissected branches.[6] In the medial branch osteofibrous tunnel, the L4 and L5 lateral branches predominate.

- Middle cluneal nerves

The middle cluneal nerves are sensory nerves derived from the dorsal rami of S1-S3. It has also been described as arising from the posterior sacral nerve plexus formed by S1-S3 dorsal rami. The nerves exit the sacral foramina and travel inferolaterally under the PSIS and across the long posterior sacroioliac ligament. The nerve route is variable, with the MCN travelling underneath the LPSP or superficial to it. The MCNs pierce the gluteus maximus and travel to the dorsal sacrum. The MCNs supplies sensory innervation overlying the intermediate medial gluteus maximus. There may be an anastamosis between the MCN and SCN.[5] The most superior branch of the MCN often anastamoses with the medial SCN distally, and this may explain why leg symptoms are common as the MCN comprises of the sensory branches of the dorsal rami of S1-S3.

Inferior cluneal nerves

The inferior cluneal nerves (ICN) arise from the posterior femoral cutaneous nerve of the thigh (PFCN), which in turn is derived from the sensory branches of S1-3. The PFCN travels with the sciatic and pudendal nerves and passes through the sciatic notch. In the subgluteal region it ramifies into the inferior cluneal and perineal branches. The nerves have a recurrent course around the inferior margin of gluteus maximus. It innervates the inferior region of the buttocks, lateral anal region (but not the anus itself), and lateral labia majora (but not labia minora or vagina).[3]

Pathophysiology

Cluneal nerve irritation may arise due to entrapment in fascia or from nerve root irritation in the epidural space or foramen. In fascial entrapment there may be a self-perpetuating process.[8] Pain may occur following spinal fusion, sacroiliac screw placement, sacral ulcer debridement, muscle flap surgeries, iliac bone harvesting, trauma, muscle spasm, spinal canal stenosis, disc herniation, scoliosis, vertebral fractures, and Parkinson's disease. [5]

- Superior cluneal nerve entrapment

Superior cluneal nerve (SCN) entrapment is thought to occur where the nerve pierces the thoracolumbar attachment at the posterior iliac crest as it becomes superficial. Typically it has been described based on cadaver studies that the medial branch of the SCN passes through an osteofibrous tunnel and can be spontaneously entrapped there.[5]

However, Kuniya et al found that in their 19 subjects requiring SCN release there were no cases of severe constriction within a bony groove on the iliac crest, but they found at least two SCN branches passing underneath a mixture of superficial thoracolumbar and gluteal fascia at the point of attachment to the iliac crest. They posited that true construction in the osteofibrous tunnel was rare, and that severe symptoms may be due to repetitive friction of the SCN under the fascia. In a further unpublished 26 cases, they had two cases of fascial constriction over the ilium.[1]

The prevalence of vertebral compression fractures is higher in those with SCN than in those without SCN disorder (26% vs 12%), most commonly at T12-L3. It is theorised that this causes a sagittal imbalance with increased kyphosis of the spine, thereby irritating the SCN at its origin from unstable facet joints or by stretching the SCN itself.[1] Maigne described thoracolumbar syndrome, whereby thoracolumbar dysfunction causes one of or a combination of unilateral iliac crest pain, lateral hip pain, and groin pain. Knight et al hypothesises that pelvic malrotation and loss of sagittal balance may be an important aetiological factor, even without vertebral fracture and irritant angulation of the cluneal nerve pathway. [8]

- Middle cluneal nerve entrapment

The MCN can become trapped while passing underneath or through the long posterior sacroiliac ligament (LPSL).[7]

Inferior cluneal nerve entrapment

Entrapment occurs with sitting and the site can be at the inferior margin of the ischium or at the level of the sciatic spine and piriformis.[3]

Epidemiology

In one retrospective review of 834 patient with LBP, 14% were thought to be due to superior cluneal nerve entrapment. However this diagnosis was made clinically (see the diagnostic method in the diagnosis section below). 62% of the clinically diagnosed patients had a 50% decreased in VAS or more. This would give a prevalence of ~8% if only including those with one or more positive injections. It is more common in middle age. Male and female distributions are roughly equal. [1]

Clinical Features

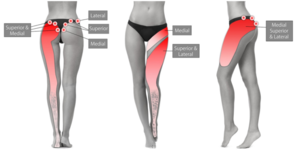

The cardinal symptom is chronic low back pain with or without leg symptoms. Knight et al believe that pelvic malalignment may be a relevant finding with pelvic anterior anteversion, and this may explain why transitional movements can be painful. Cluneal nerve pathology may exist in tandem with other spinal pathology. Symptoms may mimic sciatica.[8] Symptoms may have a neuropathic quality.[7]

- Superior cluneal nerve entrapment

In those with SCN disorder, around 50% have leg symptoms, but only 1% have leg symptoms only. The most commonly aggravating features are walking, rising from sitting, standing, flexion, and extension. Patients often find that pushing above the iliac crest with their hands relieves symptoms. Some patients have claudication like symptoms. The pain can persist for many years and some patients can be severely disabled.[1]

For medial branch SCN pain, there should be maximal tenderness over the PSIS approximately 70mm from the midline and 45mm from the PSIS. coupling rotation to contralateral side and flexion can aggravate symptoms. As can flexion and contralateral rotation. Ipsilateral hip extension may reduce pain during flexion. [1] The medial SCN branches may pass around a small palpable lipoma.[8]

For the lateral nerve group there may be tenderness near the mid-point of the iliac crest, lateral to the tubercle. They tend to be more variable in location and therefore point of irritation.[8]

- Middle cluneal nerve entrapment

There should be maximal tenderness approximately 40mm caudal to the PSIS. MCN entrapment can be confused with sacroiliac joint pain. Even a positive sacroiliac joint block could still indicate long posterior sacroiliac ligament (LPSL) pain or MCN entrapment if there is dorsal extravasation of the local anaesthetic. The S1 to S2 composition could explain why most patients with MCN entrapment get leg symptoms. [7] The MCNs can cause deep groin pain.[8]

Inferior cluneal nerve entrapment

The patient may report a history of a fall onto their buttocks. Sitting, especially on hard seats, may cause symptoms. Examine for deep tenderness along the inferior edge of the gluteus maximus between the ischium and greater trochanter. Look for hyperaesthesia with pin prick and decreased light touch sensation over the inferior buttocks. [3]

Diagnosis

- Superior cluneal nerve entrapment

There is no agreed diagnostic method. The diagnosis can be considered by tenderness over the iliac crest or LPSL causing provocation of symptoms. Pain relief following local anaesthetic injection can give further weight to the diagnosis.

Kuniya et al used the following diagnostic criteria [1]

- Maximal tenderness over the posterior iliac crest approximately 70 mm from the midline and 45 mm from the PSIS where the medial branch of the SCN runs through an osteofibrous tunnel consisting of the thoraco-lumbar fascia and the iliac crest (even if lesser tenderness exists elsewhere, for example at the thoracolumbar junction).

- Palpation of the maximally tender point reproduced the chief complaint of LBP and/or leg symptoms (Tinel-like sign)

- Temporary relief of symptoms by local anaesthetic injection

In their study, patients were included when they met the first two criteria. A nerve block injection was performed. If relief of symptoms is obtained following injection they suggest that this gives further weight to the diagnosis. In their study, if repeated injections failed to relieve symptoms then they had SCN decompression.

- Middle cluneal nerve entrapment

Again there is no agreed diagnostic method. The MCN tender point is typically on the LPSL within 40mm caudal to the PSIS.[7] Symptom relief by MCN block lends further weight to the diagnosis.

Mechanical Low Back Pain (97%)

- Internal disc disruption

- Facet joint pain

- Sacroiliac joint pain

- Sacroiliac ligament pain

- Torsion injuries

- Vertebral or sacral insufficiency fractures

- Interspinous tissue injury

- Lamina impaction

- Scoliosis

- Spondylolysis in a sportsperson, but not the general population

- The following are disputed causes of low back pain: degenerative changes, low grade disc infection, non-specific chronic low back pain, transitional vertebrae, congenital fusion, spina bifida occulta, spondylolisthesis, instability, failed back surgery syndrome, back mice, cluneal nerve entrapment, spinal stenosis, myofascial syndrome

Nonmechanical Spine Conditions (1%)

- Neoplasia (Multiple myeloma, metastatic carcinoma, lymphoma, leukaemia, spinal cord tumours, retroperitoneal tumours, primary vertebral tumours)

- Infection (Osteomyelitis, discitis, paraspinous abscess, epidural abscess, shingles)

- Spondyloarthritis

- Scheuermann disease, especially type II

- Diffuse idiopathic skeletal hyperostosis

- Osteitis Condensans Ilii

- Paget disease

Visceral Disease (2%)

- Pelvic organ involvement (Prostatitis, endometriosis, chronic pelvic inflammatory disease)

- Renal involvement (Nephrolithiasis, pyelonephritis, perinephric abscess)

- Aortic aneurysm

- Gastrointestinal involvement (Pancreatitis, cholecystitis, ulcer)

Treatment

Manual and Physical Therapy

Maigne would treat thoracolumbar syndrome with manipulation. Others have used pelvic mobilisation and pelvic realignment. Pelvic malalignment may be well-established and difficult to reverse, and Muscle Balance Therapy or Reformer Pilates could be considered.[8]

Injections

- Main article: Cluneal Nerve Injection

Trigger point injections have been described, normally with plain local anaesthetic, but it can be done with additional steroid or as dextrose prolotherapy. In Kuniya et al's study using the diagnostic criteria above, 47% required a second local anaesthetic injection, and 25% required a third injection. In those who met the first two diagnostic criteria, 62% of patients had a 50% decrease of VAS after the first injection, 67% after the second injection, and 68% after the third injection.[1]

There is very rare risk of erectile dysfunction following injections to the SCN.[1]

An ultrasound guided injection technique is shown here

Radiofrequency neurotomy has also been described [8]

Surgery

Reports have been published on SCN release and MCN release. Most reports are on SCN release. In Kuniya's study, approximately 20% of patients proceeded to SCN decompression due to failure of having long term relief from repeated SCN nerve blocks. Predictors of success were pain duration less than 3 years, and consistently having relief for three days or more from SCN blocks.[1] Long term outcomes are satisfactory.[9] See Matumoto et al for a well documented minor surgical MCN decompression technique.[10]

References

- ↑ 1.00 1.01 1.02 1.03 1.04 1.05 1.06 1.07 1.08 1.09 1.10 1.11 Kuniya et al.. Prospective study of superior cluneal nerve disorder as a potential cause of low back pain and leg symptoms. Journal of orthopaedic surgery and research 2014. 9:139. PMID: 25551470. DOI. Full Text.

- ↑ Isu et al.. Superior and Middle Cluneal Nerve Entrapment as a Cause of Low Back Pain. Neurospine 2018. 15:25-32. PMID: 29656623. DOI. Full Text.

- ↑ 3.0 3.1 3.2 3.3 Trescot, Andrea. Peripheral nerve entrapments : clinical diagnosis and management. Switzerland: Springer, 2016.

- ↑ Bogduk, Nikolai. Clinical and radiological anatomy of the lumbar spine. Edinburgh: Elsevier/Churchill Livingstone, 2012.

- ↑ 5.0 5.1 5.2 5.3 Karri et al.. Pain Syndromes Secondary to Cluneal Nerve Entrapment. Current pain and headache reports 2020. 24:61. PMID: 32821979. DOI.

- ↑ Kuniya et al.. Anatomical study of superior cluneal nerve entrapment. Journal of neurosurgery. Spine 2013. 19:76-80. PMID: 23641672. DOI.

- ↑ 7.0 7.1 7.2 7.3 7.4 Aota. Entrapment of middle cluneal nerves as an unknown cause of low back pain. World journal of orthopedics 2016. 7:167-70. PMID: 27004164. DOI. Full Text.

- ↑ 8.0 8.1 8.2 8.3 8.4 8.5 8.6 8.7 8.8 Martin Knight., et al. “A Radiofrequency Treatment Pathway for Cluneal Nerve Disorders”. EC Orthopaedics 11.3 (2020): 01-19 Full Text

- ↑ Morimoto et al.. Long-term Outcome of Surgical Treatment for Superior Cluneal Nerve Entrapment Neuropathy. Spine 2017. 42:783-788. PMID: 27669049. DOI.

- ↑ Matsumoto et al.. Surgical treatment of middle cluneal nerve entrapment neuropathy: technical note. Journal of neurosurgery. Spine 2018. 29:208-213. PMID: 29775161. DOI.

Literature Review

- Reviews from the last 7 years: review articles, free review articles, systematic reviews, meta-analyses, NCBI Bookshelf

- Articles from all years: PubMed search, Google Scholar search.

- TRIP Database: clinical publications about evidence-based medicine.

- Other Wikis: Radiopaedia, Wikipedia Search, Wikipedia I Feel Lucky, Orthobullets,