Thoracic Outlet Syndrome

Thoracic outlet syndrome (TOS) is caused by compression of the brachial plexus or subclavian vessels as they pass through the narrow passageways leading from the base of the neck to the axilla and arm. There is considerable disagreement about its diagnosis and treatment, particularly the neurogenic form. Practice guidelines are not currently possible due to the low level of evidence.[1]

Anatomy

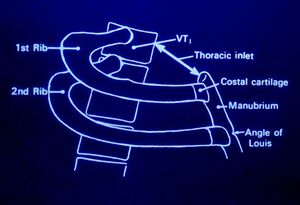

The thoracic outlet is found at the base of the neck. It consists of the first rib and adjacent structures. The upper thoracic aperture is bordered by:

- Posteriorly - spine

- Anteriorly - manubrium

- Laterally - 1st rib

The stellate ganglion sits posterior to the subclavian artery. It is anterior to the 1st rib, transverse process of C7, and the anterior primary rami of C8 and T1. It receives white rami communicantes from C8 and T1 (afferent sympathetic fibres from the brachial plexus and upper intercostal nerves). It sends grey rami communicantes to C8 and T1 (efferent sympathetic fibres to brachial plexus and intercostal nerves)

Pathophysiology

Thoracic outlet syndrome is caused by an enlargement or change of the tissues in or near the thoracic outlet leading to neurovascular compression.

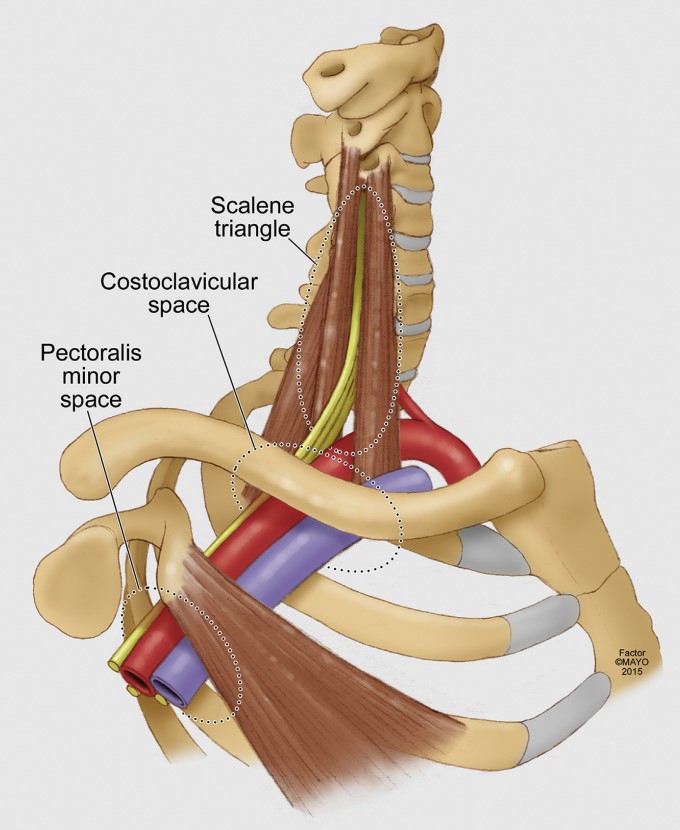

Neurovascular compression can occur at three different anatomic levels

- Interscalene triangle (between the scalene muscles)

- Costoclavicular space (between the first rib and clavicle)

- Pectoralis minor space (under the pectoralis minor)

NTOS: brachial plexus compression can occur at the interscalenne triangle or the pectoralis minor space.

VTOS: Venous compression occurs most commonly at the costoclavicular space, but can occasionally occur at the pectoralis minor space.

ATOS: Arterial compression occurs most commonly at the scalene triangle typically by an anomalous bone or ligamentous structure.[1]

Various causes have been proposed including

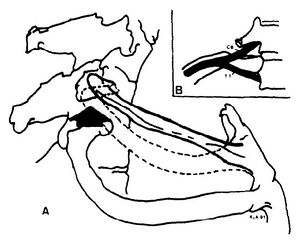

- Anomalous scalene bands. fibrous band may extend from the tip of the abnormal transverse process to the first rib.

- Anomaly or fracture of 1st rib

- Cervical rib

- Fracture clavicle

- 1st rib dysfunction. Subluxation cranially at the costotransverse joint leading to irritation of the nerve roots C8 and T1 as well as the stellate ganglion.

- Myofascial dysfunction and pain (scalenes, pectoralis minor, infraspinatus, teres minor). Restriction of internal rotation can be seen, this may be due to the fact that the axillary nerve C5/6 comes off the posterior cord (teres minor and deltoid)

- Tumour

- Repetitive trauma

- Stellate ganglion irritation causing autonomic symptoms/signs.

Often there is no direct cause.

Note that anomalies of the thoracic outlet are also common in asymptomatic individuals. In a study of 50 cadavers only 10% had a bilaterally normal anatomy.[2]

Classification

Thoracic outlet syndrome is divided into:[1]

- Neurogenic Thoracic Outlet Syndrome (NTOS): Caused by compression of the inferior trunk of the brachial plexus due to a cervical rib, band, or enlarged scalenus muscles. This is the most common form representing 85-95% of patients.

- NPMS: Neurogenic pectoralis minor syndrome is a subgroup with compression at the pectoralis minor space. If limited to the scalene triangle it is called NTOS. It combined then it is called NTOS/NPMS.

- Arterial Thoracic Outlet Syndrome (ATOS): Objective abnormality of the subclavian artery caused by extrinsic compression and subsequent damage by an anomalous first rib or analogous abnormal structure such as a cervical rib or band at the base of the scalene triangle.

- Venous Thoracic Outlet Syndrome (VTOS): Caused by compression of the subclavian vein at the costoclavicular junction, or occasionally at the pectoralis minor space.

- Paget-Schroetter syndrome: thrombotic occlusion at the costoclavicular junction, also called effort thrombosis

- McCleeery syndrome: intermittent positional obstruction in the absence of thrombosis

- VPMS: subgroup where the compression is limited to the pectoralis minor space. If limited to the costoclavicular junction it is called VTOS. If combined it is called VTOS/VPMS.

- Persistent TOS: Of any type, means that it hasn't improved after treatment

- Recurrent TOS: Symptoms have recurred after an initial three month period of improvement.

- Secondary TOS: Symptoms of a different type have occurred after treatment of a different problem.

The following terms should not be used: True, disputed, or nonspecific NTOS, vascular TOS, mixed TOS, Roos classification.

Epidemiology

The condition is more common in women. The onset of symptoms usually occurs between 20 and 50 years of age

Adolescents present much more often with venous or arterial TOS. This is because they are more likely to be athletic (VTOS), and because congenital problems will present earlier in life (ATOS).[3]

Clinical Features

History

NTOS: The patient may have pain, numbness, tingling, and weakness. Symptoms are worse when working with the arm above horizontal.

The pain is dull and aching in nature. It can occur in the shoulder, upper arm, chest, axilla, neck, head, and distal extremity. Pain can occur at night.

Ask about occupation and any potentially relevant aggravating factors such as sporting activities, driving, prolonged typing, etc. Ask about arm dominance.

Numbness and paraesthesias of the arm usually the medial arm and hand (4th and 5th fingers). There may be weakness in the shoulders, arm, and hands.

Arterial signs and symptoms can be present in patients with NTOS. However ATOS is not diagnosis unless there is proven symptomatic ischaemia. VTOS is less commonly seen in conjunction with NTOS.

VTOS: Presents as acute or chronic upper extremity deep venous thrombosis (Paget-Schroetter syndrome, effort thrombosis), or positional swelling (McCleery syndrome). The patient has arm swelling, usually with discolouration or heaviness. This may be entirely positional only occurring with the arms overhead which suggests nonthrombotic VTOS. Alternatively if present at rest then this suggests a fixed lesion i.e. subclavian vein thrombosis.

ATOS: Presents as either symptomatic ischaemia with arm elevation or fixed arterial injury (stenosis, occlusion, or aneurysm).

Examination

NTOS: There may be tenderness in the scalene triangle (NTOS), pectoralis minor insertion site (NPMS), and axilla. Pressure over the scalene triangle or pectoralis minor insertion site may reproduce symptoms.

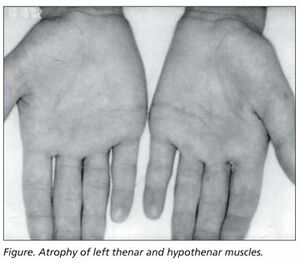

Weakness and/or paraesthesias can occur with arm elevation, pallor of the palm with arm elevation and fingers pointing to the ceiling, and weakness of the 5th finger. The patient may have the Gilliat-Sumner hand in which there is severe wasting in the fleshy base of the thumb. Atrophy of abductor pollicis brevis may mimic Carpal Tunnel Syndrome.

CRPS like signs can occur with stellate ganglion compression such as swelling of the extremities and fingers.

The first rib should be examined. The patient is seated as for examination of the cervical spine. Lateral flexion is tested bilaterally. With the head in lateral flexion, the supraclavicular area on the side of flexion is palpated. The first rib is located medially in the supraclavicular area. The patient is asked to breathe in, and the first rib rises against the pressure of the examining finger. Pain may be elicited locally. Paraesthesiae in the C8 or T1 areas may be reported.

There may be restricted abduction and internal rotation of the ipsilateral shoulder.

Examine for Tinel signs along the radial, ulnar, and median nerves.

VTOS: Examine for visible swelling at rest or with exertion, discolouration, and venous collaterals over shoulder, upper arm, or chest.

ATOS: The patient has symptoms of acute or chronic ischaemia. There is rest pain along with ischaemia with extreme exertion or arms overhead. There is paraesthesias in the arm and head. There is loss of dexterity in the hand and clumsiness of the arm. Coldness occurs with temperature sensitivity. There may be isolated finger pain or ulceration.

Special Tests

There are a variety of special tests (Table 1). The validity and reliability are hampered by the lack of a gold standard for diagnosis. The reporting standards published by Illig and colleagues recommend the following two tests for NTOS:

Elevation arm stress test (EAST): Also called Roos test. This test is used to assess for narrowing of the scalene triangle. The shoulders are abducted to 90 degrees and extended, and the elbows flexed to 90 degrees. The hands are rapidly opened and closed for up to three minutes. A positive test is reproduction of local or distal pain and neurologic symptoms. Record the time to onset of symptoms and what symptoms occurred. Symptoms at 1 minute has a lower false positive rate than symptoms at 3 minutes.

Upper limb tension test (ULTT): This is comparable to the straight leg raise of the lower limbs. It can be tested with one arm at a time or both arms at the same time to allow for easier comparison. There are three sequences, each progressively increasing tension on the brachial plexus (except the last bullet point)

- The arms are abducted to 90 degrees with the elbows extended and palms facing down.

- The wrists are dorsiflexed.

- The head is laterally flexed away from the symptomatic side.

- The elbow can then be flexed. If symptoms come on at this point then cubital tunnel syndrome shoulder be considered.

| Thoracic Outlet Syndrome Tests | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Test | Sensitivity | Specificity | +LR | -LR | Kappa |

| Cervical Rotation Lateral Flexion Test[5] | 0.92 | 0.90 | 9.2 | 0.09 | 1.0 |

| Both Adson + Wright (pulse) positive | 0.54 | 0.94 | 9.0 | 0.5 | |

| Both Adson + hyperabduction (sx) positive | 0.72 | 0.88 | 6 | 0.3 | |

| Hyperabduction (pulse abolition) | 0.52 | 0.90 | 5.2 | 0.5 | |

| Both Adson + Roos positive | 0.72 | 0.82 | 4 | 0.3 | |

| Both Adson + Wright (sx) positive | 0.79 | 0.76 | 3.3 | 0.3 | |

| Both Adson + Roos positive | 0.72 | 0.82 | 4 | 0.3 | |

| Adson test | 0.79 | 0.76 | 3.3 | 0.3 | |

| Tinel sign | 0.86 | 0.56 | 2.0 | 0.3 | |

| Both Wright (pulse) + hyperabduction (sx) positive | 0.63 | 0.69 | 2.0 | 0.5 | |

| Both Wright (sx) + hyperabduction (sx) positive | 0.83 | 0.50 | 1.7 | 0.3 | |

| Both Wright (sx) + Roos positive | 0.83 | 0.47 | 1.6 | 0.4 | |

| Wright test (pulse abolition) | 0.70 | 0.53 | 1.5 | 0.6 | |

| Hyperabduction (sx reproduction) | 0.84 | 0.40 | 1.4 | 0.4 | |

| Wright test (sx reproduction) | 0.90 | 0.29 | 1.3 | 0.3 | |

| Elevated Arm Stress Test/Roos (EAST) | 0.84 | 0.30 | 1.2 | 0.5 | |

Investigations

Imaging

Plain films: Chest and cervical spine xrays should be requested to assess for cervical rib or elongated C7 transverse process.

Other: Venous and arterial anatomy can be assessed by catheter angiography, doppler, or MR angiography and venography.

Electrophysiology

Electrophysiological tests: These are typically normal below the clavicle and are not required for diagnosis unless a specific disorder other than NTOS is suspected. However in some cases there may be the following findings in classic neurogenic TOS:

- Low compound muscle action potential in the thenar and intrinsic muscles

- Abnormal sensory nerve conduction in the ulnar nerve

- Prolonged F-wave latency in the ulnar nerve

- Abnormal medial antebrachial cutaneous sensory nerve conduction)

TOS Muscle Test Block

The most modern version of this test targets the terminal branches of the intramuscular nerves of the anterior scalene, subclavius, and pectoralis minor. The test has evolved over the years increasing the diagnostic validity. Older techniques only targeted the anterior scalene which resulted in high rates of false negatives due to failure to block more distal sites of potential compression.

A positive test temporarily improves symptoms due to muscle relaxation leading to reduced tension on the neurovascular structures between the muscles in the interscalene triangle and dropping of the first rib. If the symptoms are temporarily reversed with selective blockade then surgical decompression is more likely to be successful.

The gold standard test block for NTOS is a single multi site injection that includes controls for placebo effects and examiner bias. Live combined ultrasound and EMG guidance is performed to ensure accurate placement of the injection and to confirm small volumes of injectant to the motor innervation within the muscle, while avoiding spread across tissue planes. When done the following way at an experienced centre the true-positive rate is 96% with the gold standard being a good outcome from botulinum chemodenervation or thoracic outlet decompression (879 cases). The false negative rate is 27%. Failure to double blind increases the risk of poor outcome from decompression.[6]

Occasionally weeks or months of therapeutic benefit may result from the test injection, but the primary purpose is for diagnosis.

Pre-procedure: The patient is instructed about the need for double blinding and that either a short or long acting anaesthetic will be injected into the targeted muscles including the anterior scalene, subclavius, and pectoralis minor. In some cases it may be appropriate to perform sequential, staged blocks where blocks of isolated muscles are done at different dates.

They are shown how to keep an hourly pain diary for measurement of pain, numbness, and weakness at rest and with stress manoeuvres including the one minute EAST test every hour while awake and the following morning. They are also asked to perform any activities that usually bring about symptoms. They are coached to focus on either a 1 hour or 5 hour response. The anaesthetic used is determined by a coin flip by someone other than the doctor and placed in a sealed envelope.

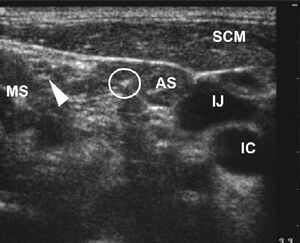

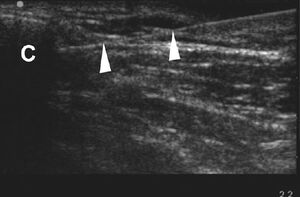

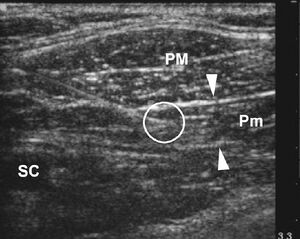

Position: The patient is in a semi rotated supine position with the upper body elevated to 30 degrees and the shoulder rotated off the table with a wedge.

Monitoring: Combined EMG and live ultrasound is performed throughout. EMG is a critical addition in two circumstances. Firstly it confirms the ultrasound appearance with seeing the needle tip in the muscle. Without EMG the doctor does not know if the muscle is simply being invaginated and not penetrated. The second benefit is that it allows monitoring of intramuscular location when the tip of the needle is obscured by the clavicle during injection of the subclavius muscle.

Active Target: The target muscles are anterior scalene, subclavius, and pectoralis minor. The muscles of interest are targeted in the mid belly region with a 25 gauge Teflon coated hypodermic EMG and injection needle. EMG recording confirms high frequency motor unit activity at rest that is consistent with clinically observed dystonia. Motor thresholds are applied and a twitch on ultrasound is observed at approximaly 1 mA.

The patient is asked to respond upon feeling the effects of EMG stimulation. Pain intensity and concordance with typical pain patterns are recorded. The recording nurse is blinded to the muscle being injected.

The anterior scalene, subclavius, and pectoralis minor are sequentially subjected to the above targeting procedure and injected with 1mL of anaesthetic and 1mg of dexamethasone. Live ultrasound observes injectant flow along the targeted muscle and not into the plexus.

Controls: Control muscles are similarly injected with saline, such as the trapezius and sternocleidomastoid.

Interpretation: The pain diaries are returned the following day and interpreted prior to revealing the identify of the injectant. A valid response is 50% or greater reduction in the pain scale at rest and with provocation for a time that is concordant with the expected duration of the anaesthetic. Provocation testing should reveal concordant pain responses from the scalene, subclavius, or pectoralis muscles and not from control muscles. Unexpectedly long or short responses can be interpreted as placebo or non specific effects.

A negative response is a lack of improvement in symptoms. This can occur due to incorrect diagnosis, technical issues, or a fixed plexus compression by bony or soft tissue anomalies such as extensive scalene or pectoralis muscle fibrosis. Therefore a negative result can't fully exclude NTOS but lowers the chance of a successful outcome with treatment.

Differential Diagnosis

- Rotator Cuff Tendinopathy

- Cervical disc disorders

- C7 or C8 nerve root compression

- Ulnar neuropathy

- Carpal Tunnel Syndrome

- Fibromyalgia

- Multiple Sclerosis

- CRPS

- Raynauds Syndorme

- Cervical dystonia

- Neuralgic Amyotrophy or other brachial plexus injury

- Syringomyelia

- Vasculitis

- Scleroderma

- Lymphoedema

- Acromioclavicular Joint Pain

- Pancoast tumour

Diagnosis

Thoracic outlet syndrome is a "fuzzy" diagnosis. It is a valid entity but it difficult to diagnose, and it can overlap with multiple other problems.[7]

NTOS: The diagnosis of NTOS can be made when three of the following four criteria are present:[1]

- LOCAL FINDINGS:

- History: Symptoms consistent with irritation or inflammation at the site of compression (scalene triangle for NTOS, and pectoralis insertion for NPMS), plus symptoms due to referred pain. Patients may have pain in the chest, axilla, upper back, shoulder, trapezius, neck, or head.

- Examination: Tenderness of the affected area.

- PERIPHERAL FINDINGS:

- History: Arm or hand symptoms consistent with proximal nerve compression. Symptoms include numbness, pain, paraesthesias, vasomotor changes, and weakness. Muscle wasting can occur in extreme cases. Symptoms are exacerbated by movements that either narrow the thoracic outlet (lifting arms overhead) or stretch the brachial plexus (dangling, driving, walking/running).

- Examination: Reproduction of peripheral symptoms with palpation of the affected area (scalene triangle or pectoralis minor insertion site). The EAST or ULTT test may provoke symptoms.

- ABSENT FINDINGS:

- Cervical disc disease, shoulder disease, carpal tunnel syndrome, chronic regional pain syndrome, brachial neuritis.

- INJECTION:

- Response to a properly performed test injection

VTOS: As many as possible of the following are required.

- HISTORY: Swelling, discoloration, heaviness, pain. Worse with arms overhead, driving, or exercising. Dilated veins in shoulder or chest.

- EXAMINATION: Swelling and discoloration at rest and with arms elevated

- IMAGING: Consistent imaging findings

- TOS Disability scale

ATOS: As many as possible of the following are required

- HISTORY: classic symptoms or acute or chronic ischaemia

- EXAMINATION: objective findings of ischaemia. Note that loss of pulse or discolouration with provocative manoeuvres in those with NTOS is not sufficient to diagnosis ATOS.

- IMAGING: Objective imaging findings of subclavian artery compression along with the presence or absence of a cervical rib, elongated transverse process, or anomalous first rib.

- TOS Disability scale.

Treatment

Nonsurgical treatment

Malfunction of the first rib: isometric contraction of scalenus anterior and medius results in elevation of the first rib anteriorly, and reduces posterior subluxation. The therapist places their hand over the lateral head with the patient in a seated position. The patient contracts against the therapists hand. Gentle mobilisations are done over 20 seconds.

Postural dysfunction: Spinal postural stability; release tight pectoralis minor (pec minor may be tight without 1st rib dysfunction with arm elevation), scalene and shoulder girdle muscles (e.g. infraspinatus and teres minor); maintain cervicothoracic mobility; strengthen scapula muscles, lower and middle trapezius, and serratus anterior; strengthen rotator cuff; address ergonomic factors; address work behaviour factors.

General: Ergonomic modifications at workplace and home.

Injections: Botulinum chemodenervation

Surgery: Decompression of the thoracic outlet. Options include the following which can be done as individual procedures or combined. In properly selected patients at a specialised centre, surgery is successful in 80-90% of cases of NTOS.

- Pectoralis minor tenotomy. This can be a good treatment options in suitable patients and can be performed as an outpatient in 30 minutes.

- Supraclavicular decompression with scalenectomy

- First rib resection

- Brachial plexus neurolysis.

Prognosis

The prognosis is better in younger patients.

See Also

Reporting standards are by Illig et al. [1] This group at UCLA has published a large body of literature including a book.[6]

References

- ↑ 1.0 1.1 1.2 1.3 1.4 Illig et al.. Reporting standards of the Society for Vascular Surgery for thoracic outlet syndrome. Journal of vascular surgery 2016. 64:e23-35. PMID: 27565607. DOI.

- ↑ Juvonen T, Satta J, Laitala P, Luukkonen K, Nissinen J. Anomalies at the thoracic outlet are frequent in the general population. Am J Surg. 1995 Jul;170(1):33-7. doi: 10.1016/s0002-9610(99)80248-7. PMID: 7793491.

- ↑ Chang K, Graf E, Davis K, Demos J, Roethle T, Freischlag JA. Spectrum of thoracic outlet syndrome presentation in adolescents. Arch Surg. 2011 Dec;146(12):1383-7. doi: 10.1001/archsurg.2011.739. PMID: 22184299.

- ↑ Gillard et al.. Diagnosing thoracic outlet syndrome: contribution of provocative tests, ultrasonography, electrophysiology, and helical computed tomography in 48 patients. Joint bone spine 2001. 68:416-24. PMID: 11707008. DOI.

- ↑ Lindgren KA, Leino E, Manninen H. Cervical rotation lateral flexion test in brachialgia. Arch Phys Med Rehabil. 1992 Aug;73(8):735-7. PMID: 1642524.

- ↑ 6.0 6.1 6.2 6.3 6.4 Illig, Karl A. Scalene Test Blocks and Interventional Techniques in Patients with TOS In: Thoracic outlet syndrome. London New York: Springer, 2013.

- ↑ Illig KA. Thoracic outlet syndrome in adolescents is real: comment on "Spectrum of thoracic outlet syndrome presentation in adolescents". Arch Surg. 2011 Dec;146(12):1388. doi: 10.1001/archsurg.2011.1026. PMID: 22184300.

Literature Review

- Reviews from the last 7 years: review articles, free review articles, systematic reviews, meta-analyses, NCBI Bookshelf

- Articles from all years: PubMed search, Google Scholar search.

- TRIP Database: clinical publications about evidence-based medicine.

- Other Wikis: Radiopaedia, Wikipedia Search, Wikipedia I Feel Lucky, Orthobullets,