Transitional Vertebral Anatomy: Difference between revisions

No edit summary |

No edit summary |

||

| Line 1: | Line 1: | ||

{{partial}} | {{partial}} | ||

{{condition | |||

|image= | |||

|name= | |||

|taxonomy=Pseudarthrosis of a Transitional Vertebra (XXVI-7), no taxonomy for other causes of pain. | |||

|synonym= | |||

|definition= | |||

|epidemiology= | |||

|causes= | |||

|pathophysiology= | |||

|classification= | |||

|primaryprevention= | |||

|secondaryprevention= | |||

|riskfactors= | |||

|history= | |||

|examination= | |||

|diagnosis= | |||

|tests= | |||

|ddx= | |||

|treatment= | |||

|prognosis= | |||

}} | |||

[[File:LSTV Type 2a.jpg|400px|thumb|right|Right sided Castellvi type 2a LSTV in a patient with contralateral left sided lumbosacral pain, tenderness over the left upper one third dorsal sacroiliac ligamentous area, and pelvic malalignment with a right pelvic upslip.]] | [[File:LSTV Type 2a.jpg|400px|thumb|right|Right sided Castellvi type 2a LSTV in a patient with contralateral left sided lumbosacral pain, tenderness over the left upper one third dorsal sacroiliac ligamentous area, and pelvic malalignment with a right pelvic upslip.]] | ||

The most common vertebral arrangement is of 24 presacral vertebrae, consisting of 7 cervical, 12 thoracic, and 5 lumbar vertebrae. The cervical spine has a fixed vertebral count of 7, however the lumbar and thoracic vertebrae counts can be variable. Transitional vertebrae occur when there is overlap of developing somites during cranial-caudal border shifting. The vertebrae affected have morphology of a combined nature of the two adjacent vertebral regions. | The most common vertebral arrangement is of 24 presacral vertebrae, consisting of 7 cervical, 12 thoracic, and 5 lumbar vertebrae. The cervical spine has a fixed vertebral count of 7, however the lumbar and thoracic vertebrae counts can be variable. Transitional vertebrae occur when there is overlap of developing somites during cranial-caudal border shifting. The vertebrae affected have morphology of a combined nature of the two adjacent vertebral regions. | ||

| Line 85: | Line 107: | ||

*Facet joint arthrosis contralateral to the unilateral fused or articulating LSTV | *Facet joint arthrosis contralateral to the unilateral fused or articulating LSTV | ||

*Extraforaminal stenosis secondary to a broadened transverse process. | *Extraforaminal stenosis secondary to a broadened transverse process. | ||

The implicated segments are normally types II-IV.<ref name="konin"/> However it is thought that type I segments with their broadened transverse processes and broadened and short iliolumbar ligaments may lead to a protective effect of the L5-S1 disc space and possibly destabilise the L4-5 level. | The implicated segments are normally types II-IV.<ref name="konin"/> However it is thought that type I segments with their broadened transverse processes and broadened and short iliolumbar ligaments may lead to a protective effect of the L5-S1 disc space and possibly destabilise the L4-5 level. | ||

| Line 94: | Line 115: | ||

Assessing for nerve root symptoms in the presence of an LSTV lends to a few considerations, and may complicate assessment. Extraforaminal stenosis can occur with a nerve root being compressed between the hyperplastic transverse process of the LSTV and the adjacent sacral ala. Another explanation for nerve root symptoms is that disc prolapse can occur at the level above the LSTV at a greater rate than for those without an LSTV. Furthermore, in the absence of spondylolisthesis, spinal stenosis is also more likely to occur at the level above the LSTV. Examination is complicated by the fact that there is variation in lower limb myotomes in those with an LSTV. With a sacralised L5, the L4 nerve root functions as the L5 nerve root. With a lumbarised S1, the S1 nerve root functions as the L5 nerve root. The functional L5 nerve root always originates at the lowest mobile lumbosacral level.<ref name="konin"/> | Assessing for nerve root symptoms in the presence of an LSTV lends to a few considerations, and may complicate assessment. Extraforaminal stenosis can occur with a nerve root being compressed between the hyperplastic transverse process of the LSTV and the adjacent sacral ala. Another explanation for nerve root symptoms is that disc prolapse can occur at the level above the LSTV at a greater rate than for those without an LSTV. Furthermore, in the absence of spondylolisthesis, spinal stenosis is also more likely to occur at the level above the LSTV. Examination is complicated by the fact that there is variation in lower limb myotomes in those with an LSTV. With a sacralised L5, the L4 nerve root functions as the L5 nerve root. With a lumbarised S1, the S1 nerve root functions as the L5 nerve root. The functional L5 nerve root always originates at the lowest mobile lumbosacral level.<ref name="konin"/> | ||

====Pseudoarthrosis==== | |||

The IASP lists pseudoarthrosis of a transitional vertebra in their taxonomy, but not other potential causes of pain in transitional anatomy. It isn't clear to the author if this is an intentional or unintentional omission. The relevant pathology may be a periostitis that occurs due to repeated contact between the two bones with resultant sclerosis, but the majority are asymptomatic. They state that the diagnostic criteria are that the pseudoarthrosis must be present radiographically, and the pain must be relieved with selective aneasthetic injection of the pseudoarthrosis without having the anaesthetic spread to other structures that might suggest an alternative source of pain.<ref>Pseudarthrosis of a Transitional Vertebra (XXVI-7). Classification of Chronic Pain, Second Edition (Revised). IASP. https://www.iasp-pain.org/PublicationsNews/Content.aspx?ItemNumber=1673</ref> | |||

===Treatment=== | ===Treatment=== | ||

Revision as of 18:20, 5 May 2021

| Transitional Vertebral Anatomy | |

|---|---|

| Taxonomy | Pseudarthrosis of a Transitional Vertebra (XXVI-7), no taxonomy for other causes of pain. |

The most common vertebral arrangement is of 24 presacral vertebrae, consisting of 7 cervical, 12 thoracic, and 5 lumbar vertebrae. The cervical spine has a fixed vertebral count of 7, however the lumbar and thoracic vertebrae counts can be variable. Transitional vertebrae occur when there is overlap of developing somites during cranial-caudal border shifting. The vertebrae affected have morphology of a combined nature of the two adjacent vertebral regions.

Some people with transitional anatomy have 23 or 25 presacral segments. The most common variations are the presence of 13 rib-bearing thoracic vertebrae with four lumbar-type vertebrae, and 12 rib-bearing thoracic vertebrae with six lumbar-type vertebrae.

Transitional anatomy can also occur at the atlanto-occipital junction (atlanto-occipital assimilation: complete or partial fusion of C1 and the occiput, occipital vertebra: an additional bone between C1 and the occiput), and at the cervicothoracic junction (cervical rib arising from C7).

It is important to accurately describe transitional anatomy as failing to do so can lead to surgery or interventions done at the incorrect level, and it can confound the neurological examination with variations in the myotomes.[1]

Prevalence

- The lumbarisation of S1 occurs in around 2% of the population. The sacralisation of L5 occurs in around 17% of the population.[2]

- Thoracolumbar transitional anatomy prevalence is unknown.[3]

- Cervical ribs occur in around 0.2 to 0.5% of the population

Lumbosacral Transitional Anatomy

| TV Location | Frequency | Vertebral Segments | Anatomical Features | Nerve Root Changes |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| L5 sacralisation | ~9/10 of LSTV | 4 rib-free lumbar vertebrae | wedging of the lowest lumbar (transitional) vertebra hypoplastic or absent facet joints or intervertebral disc |

The L4 nerve root tends to serve the usual function of the L5 nerve root*. |

| S1 lumbarisation | ~1/10 of LSTV | 6 rib-free lumbar vertebrae | squaring of highest sacral (transitional) vertebra facet joints (even rudimentary) and intervertebral disc between S1 and S2 |

The S1 nerve root may or may not serve the usual function of the L5 nerve root*. |

| *The functional L5 nerve root may originate at the lowest mobile lumbosacral level. | ||||

Numbering Technique

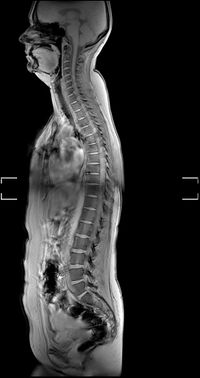

It can be difficult to establish whether a LSTV is a lumbarised S1 or a sacralised L5, and there have been various techniques described, with the best technique being high quality imaging of the entire spine.[1] MRI reports should state the method of numbering and how the LSTV was determined.

Survey sequences

In New Zealand, some private radiology providers will do a sagittal survey sequence of the entire spine (also called a sagittal localiser) as routine while others do not. You then count from the odontoid peg of C2 inferiorly, rather than counting cranially from L5. One can identify the L1 vertebral body, and subsequently determine the correct numeric assignment of the LSTV. Radiographs of the entire spine can fulfil the same purpose. If there is only a normal lumbar spine radiograph, then correct numeration may still be possible, but it can be tricky at the thoracolumbar junction to differentiate the hypoplastic rib from the transverse process. Thoracolumbar transitions can also make things difficult without a full spine view.[1]

Using a sagittal localiser sequence assumes there are 7 cervical and 12 thoracic vertebra. The method does not account for thoracolumbar transitional anatomy or allow one to differentiate between dysplastic ribs and lumbar transverse processes. Adding a coronal localising sequence can sometimes increase the accuracy of locating the thoracolumbar junction.[1]

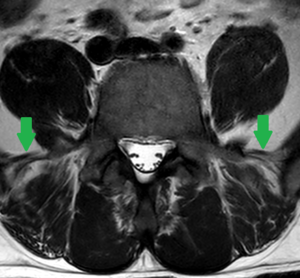

Iliolumbar ligament

Locating the iliolumbar ligament is another technique described. This ligament is present at the L5 transverse process in 96.8% of people.[4] On MRI it is a low signal intensity structure on T1 and T2 images and looks like a single or double band that extends from the transverse process of L5 to the posteromedial iliac crest. It serves to restrict flexion, extension, axial rotation, and lateral bending of L5 on S1. As with other landmarks, identification of the iliolumbar ligament is not sufficient to identify the L5 vertebral body, but it can be used to identify the lumbosacral junction as it identifies the lowest lumbar type vertebral segment.[4]

Other anatomic markers

Using other markers such as the aortic bifurcation, right renal artery, and conus medullaris has also been described and are not satisfactory.[1]

Other features

The lumbarised S1 may be squared and have facet joints and an intervertebral disc. The sacralised L5 may be wedged and have hypoplastic or absent jacet joints or intervertebral disc.

Castellvi classification

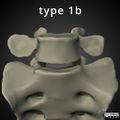

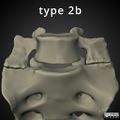

| Type | Features |

|---|---|

| Type Ia | A unilateral TP height greater than or equal to 19 mm |

| Type Ib | Both processes heights greater than or equal to 19 mm |

| Type IIa | Presence of unilateral articulation between the TP and the sacrum |

| Type IIb | Presence of bilateral articulation between the TP and the sacrum |

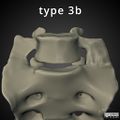

| Type IIIa | Unilateral fusion of the TP and the sacrum |

| Type IIIb | Bilateral fusion of the TP and the sacrum |

| Type IV | Unilateral type II transition (articulation) with a type III (fusion) on the contralateral side |

Bertolotti Syndrome

Bertolotti syndrome, the association between low back pain and LSTV, is controversial. A LSTV is certainly present in large numbers of asymptomatic people, but may be more common in those with back pain. Pain associated with LSTV is currently thought to arise from various different structures[1]

- Disc, spinal canal, and the posterior elements above the transition.

- Degenerative change of the LSTV articulation

- Facet joint arthrosis contralateral to the unilateral fused or articulating LSTV

- Extraforaminal stenosis secondary to a broadened transverse process.

The implicated segments are normally types II-IV.[1] However it is thought that type I segments with their broadened transverse processes and broadened and short iliolumbar ligaments may lead to a protective effect of the L5-S1 disc space and possibly destabilise the L4-5 level.

Theoretically the LSTV will alter the biomechanics of the spine, and cause some stabilisation at this level. Structural pathology (disc integrity and spinal and foraminal stenosis) occurs almost exclusively at the level above the transitional segment, and never between the LTSV and the sacrum, with normal bright signal intensity on T2 weighted sequences on MRI at the LSTV. The level above the LSTV may be hypermobile at the ipsilateral anomalous articulation and/or the contralateral facet joint. Potentially relevant is that the liliolumbar ligaments above an LSTV are thinner and weaker at the level above the LSTV, resulting in destabilisation. The pseudoarticulated type 2 LSTVs have increased tracer uptake, while the fused type 3 LSTVs do not, and may be transmitting the forces superiorly or to the contralateral facet joint.[1]

Some of these changes may be akin to the adjacent-level disease seen post fusion, with hypermobility accelerating degenerative change at the facet joints and disc. This analogy could also explain the increased rate of contralateral facet joint arthrosis in unilateral type 2 and type 3 LSTVs, with forces being transmitted to the contralateral side.[1]

Assessing for nerve root symptoms in the presence of an LSTV lends to a few considerations, and may complicate assessment. Extraforaminal stenosis can occur with a nerve root being compressed between the hyperplastic transverse process of the LSTV and the adjacent sacral ala. Another explanation for nerve root symptoms is that disc prolapse can occur at the level above the LSTV at a greater rate than for those without an LSTV. Furthermore, in the absence of spondylolisthesis, spinal stenosis is also more likely to occur at the level above the LSTV. Examination is complicated by the fact that there is variation in lower limb myotomes in those with an LSTV. With a sacralised L5, the L4 nerve root functions as the L5 nerve root. With a lumbarised S1, the S1 nerve root functions as the L5 nerve root. The functional L5 nerve root always originates at the lowest mobile lumbosacral level.[1]

Pseudoarthrosis

The IASP lists pseudoarthrosis of a transitional vertebra in their taxonomy, but not other potential causes of pain in transitional anatomy. It isn't clear to the author if this is an intentional or unintentional omission. The relevant pathology may be a periostitis that occurs due to repeated contact between the two bones with resultant sclerosis, but the majority are asymptomatic. They state that the diagnostic criteria are that the pseudoarthrosis must be present radiographically, and the pain must be relieved with selective aneasthetic injection of the pseudoarthrosis without having the anaesthetic spread to other structures that might suggest an alternative source of pain.[6]

Treatment

Treatment options include:[1]

- Conservative management

- Contralateral facet joint: injections, radiofrequency neurotomy, surgical excision

- Ipsilateral transeverse process: surgical resection, injections of the pseudoarthrosis.

A systematic review by Holm et al in 2017 concluded that the evidence was low quality and no conclusions could be made. They found that steroid injections could improve symptoms but only temporarily, and surgical management could improve symptoms over time, but there were no head to head trials.[7]

Thoracolumbar Transitional Anatomy

Throacolumbar transitional vertebrae (TLTV) may have hypoplastic ribs of <38mm in length, but this feature is not sufficient for detection.

| TV Location | Frequency | Vertebral Segments | Anatomical Features |

|---|---|---|---|

| T12 | ~2/3 of TLTV | 24 (No additional) | Superior facets not directly posteriorly Intermediate mamillary bodies No prominent transverse process |

| L1 | ~1/3 of TLTV | Mostly 24 Rarely 25 with 6 lumbar vertebra Rarely 25 with 13 thoracic vertebra and ribs |

No costal facets for ribs. Transverse process aplasia/hypoplasia Superior facets asymmetrical and more posterior Remnant mamillary bodies |

Other Articles

- See Konin et al for an open access review on the lumbosacral transitional vertebral (LSTV) anatomy.[1]

- See Furman et al for a practical approach, but unfortunately it is not open access.[8]

References

- ↑ 1.00 1.01 1.02 1.03 1.04 1.05 1.06 1.07 1.08 1.09 1.10 1.11 Konin & Walz. Lumbosacral transitional vertebrae: classification, imaging findings, and clinical relevance. AJNR. American journal of neuroradiology 2010. 31:1778-86. PMID: 20203111. DOI.

- ↑ Uçar et al.. Retrospective cohort study of the prevalence of lumbosacral transitional vertebra in a wide and well-represented population. Arthritis 2013. 2013:461425. PMID: 23864947. DOI. Full Text.

- ↑ 3.0 3.1 3.2 Du Plessis et al.. Differentiation and classification of thoracolumbar transitional vertebrae. Journal of anatomy 2018. 232:850-856. PMID: 29363131. DOI. Full Text.

- ↑ 4.0 4.1 Carrino et al.. Effect of spinal segment variants on numbering vertebral levels at lumbar MR imaging. Radiology 2011. 259:196-202. PMID: 21436097. DOI.

- ↑ Castellvi et al.. Lumbosacral transitional vertebrae and their relationship with lumbar extradural defects. Spine 1984. 9:493-5. PMID: 6495013. DOI.

- ↑ Pseudarthrosis of a Transitional Vertebra (XXVI-7). Classification of Chronic Pain, Second Edition (Revised). IASP. https://www.iasp-pain.org/PublicationsNews/Content.aspx?ItemNumber=1673

- ↑ Holm et al.. Symptomatic lumbosacral transitional vertebra: a review of the current literature and clinical outcomes following steroid injection or surgical intervention. SICOT-J 2017. 3:71. PMID: 29243586. DOI. Full Text.

- ↑ Furman et al.. Lumbosacral Transitional Segments: An Interventional Spine Specialist's Practical Approach. Physical medicine and rehabilitation clinics of North America 2018. 29:35-48. PMID: 29173663. DOI.

Literature Review

- Reviews from the last 7 years: review articles, free review articles, systematic reviews, meta-analyses, NCBI Bookshelf

- Articles from all years: PubMed search, Google Scholar search.

- TRIP Database: clinical publications about evidence-based medicine.

- Other Wikis: Radiopaedia, Wikipedia Search, Wikipedia I Feel Lucky, Orthobullets,