Acute Neck Pain: Difference between revisions

| Line 34: | Line 34: | ||

==Management== | ==Management== | ||

===Passive Treatment=== | ===Passive Treatment=== | ||

Bogduk recommends, writing in 2006, to avoid passive therapy. He states that it is not effective | Bogduk recommends, writing in 2006, to avoid passive therapy. He states that it is not significantly more effective than other methods. Passive management assumes that a specific diagnosis has been made, and that passive treatment will rectify said diagnosis. However no conventional examination or investigation can identify the pathology and no conventional treatment can target or resolve any specific cause of pain. | ||

In a randomised controlled trial of patients with neck pain for at least two weeks (most patients less than 13 weeks), once weekly manual therapy (muscular mobilisation, specific articular mobilisation, coordination or stabilisation) was more clinically effective and more cost effective than twice weekly physiotherapy (individualised exercise therapy, including active and postural or relaxation exercises, stretching, and functional exercises) and continued general practitioner care (explanation, home exercises, reassurance, medication) over six weeks.<ref>{{#pmid:12020139}}</ref><ref>{{#pmid:12714472}}</ref> At 7 weeks, 68.3% of patients in the manual therapy group reported resolved or much improved pain, compared with 50.8% of patients in the physical therapy group and 35.9% of patients in the continued care group. This equates to an NNT of 5.7 of manual therapy over exercise therapy, and an NNT of 3 over general practitioner care. Longitudinal follow up showed that the treatment effect was lost by weeks 13 and 52.<ref>{{#pmid:16691091}}</ref>. Interestingly, this effect occurred despite there being more patients with chronic pain in the manual therapy and physiotherapy groups than the continued care group (30%, 28.8%, and 18.8% respectively). The study has been criticised for using "perceived recovery" as the primary outcome measure. Also the manual therapy group averaged six visits, versus two visits for GP care, and so the greater success could be due to the increased intensity of patient-therapist interactions. | |||

A systematic review stated that due to heterogeneity, no definite conclusions could be made.<ref>{{#pmid:22447407}}</ref> | A systematic review stated that due to heterogeneity, no definite conclusions could be made.<ref>{{#pmid:22447407}}</ref> | ||

Revision as of 18:25, 6 June 2021

Aetiology

- Main article: Causes and Sources of Neck Pain

The causes of common acute neck pain are largely unknown, however any structure in the cervical spine that is innervated is a potential source of pain. Importantly, cervical spondylosis is not a legitimate cause of neck pain. Serious and identifiable causes of neck pain - infections, fractures, tumours, dissection - are rare, but vigilance is required to detect them. Many review articles and textbooks list things like neurological and rheumatological conditions, but in these conditions there is usually another give away and so they are not generally part of the true differential of isolated acute neck pain.

Clinical Assessment

- Significant trauma (eg. fall in osteoporotic patient, motor vehicle accident)

- Infective: (eg. fever, meningism, immunosuppression, intravenous drug use, exotic exposure, recent overseas travel)

- Constitutional: (eg. fevers, weight loss, anorexia, past or current history of malignancy)

- Iatrogenic: Recent surgery, catheterisation, venipuncture, manipulation

- Neurological: Symptoms/signs especially of upper motor neuron pathology, vomiting

- Genitourinary/Reproductive: UTI, haematuria, retention, uterine, breast

- Endocrine: Corticosteroids, diabetes, hyperparathyroid

- Gastrointestinal: Dysphagia

- Integumentary: Infections, rashes

- Cardiorespiratory: Cough, haemoptysis, chest pain, shortness of breath, diaphoresis, ripping/tearing sensation (dissection), CVD risk factors, anticoagulants

- Rheumatological: History of rheumatoid arthritis (atlanto-axial disruption)

- Awkward posture (atlantoaxial rotatory subluxation in children)

It is rarely possible to establish a patho-anatomic diagnosis in acute neck pain, and so the diagnostic process is one of exclusion.

The first step is evaluating whether the patient has neurological symptoms or signs. If they do then they should be assessed under a neurological disorders framework rather than an acute neck pain framework as the neurological disorder takes precedence. Neurological disorders include spinal cord injury, myelopathy, and radiculopathy.

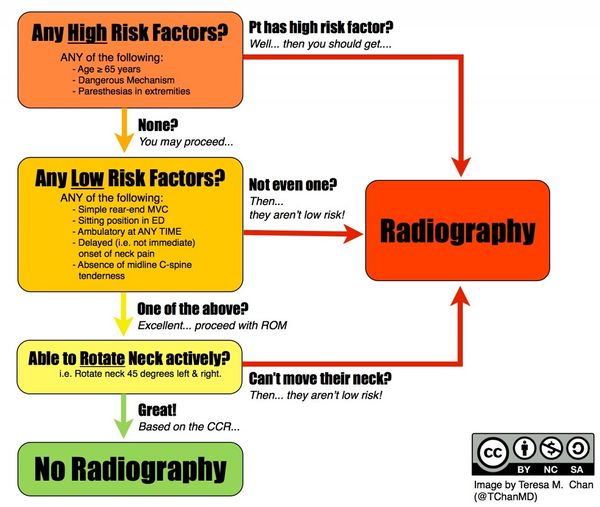

In the event of trauma, the Canadian C-spine rule should be used, and any fracture managed as appropriate.

The practitioner should remain vigilant to new clues that invites revisiting the diagnosis. Vigilance includes revisiting red flag symptoms and noting any new symptoms or signs.

Diagnosis

For patients with no history of injury the diagnosis used by the Australian Acute Musculoskeletal Guidelines is "idiopathic neck pain," while for those with neck pain following a motor vehicle accident the diagnosis is "whiplash-associated neck pain." For ACC medicolegal purposes the coding that should be used is normally "cervical sprain," but this is not a meaningful label in a medical sense as it lacks legitimacy as a diagnosis.

Management

Passive Treatment

Bogduk recommends, writing in 2006, to avoid passive therapy. He states that it is not significantly more effective than other methods. Passive management assumes that a specific diagnosis has been made, and that passive treatment will rectify said diagnosis. However no conventional examination or investigation can identify the pathology and no conventional treatment can target or resolve any specific cause of pain.

In a randomised controlled trial of patients with neck pain for at least two weeks (most patients less than 13 weeks), once weekly manual therapy (muscular mobilisation, specific articular mobilisation, coordination or stabilisation) was more clinically effective and more cost effective than twice weekly physiotherapy (individualised exercise therapy, including active and postural or relaxation exercises, stretching, and functional exercises) and continued general practitioner care (explanation, home exercises, reassurance, medication) over six weeks.[1][2] At 7 weeks, 68.3% of patients in the manual therapy group reported resolved or much improved pain, compared with 50.8% of patients in the physical therapy group and 35.9% of patients in the continued care group. This equates to an NNT of 5.7 of manual therapy over exercise therapy, and an NNT of 3 over general practitioner care. Longitudinal follow up showed that the treatment effect was lost by weeks 13 and 52.[3]. Interestingly, this effect occurred despite there being more patients with chronic pain in the manual therapy and physiotherapy groups than the continued care group (30%, 28.8%, and 18.8% respectively). The study has been criticised for using "perceived recovery" as the primary outcome measure. Also the manual therapy group averaged six visits, versus two visits for GP care, and so the greater success could be due to the increased intensity of patient-therapist interactions.

A systematic review stated that due to heterogeneity, no definite conclusions could be made.[4]

Explanation and Reassurance

These often go together. Elicit the patient's ideas and concerns. Gently correct false beliefs and address any fears about serious causes or about the prognosis. A clinical assessment can effectively rule out sinister causes and so the clinician can provide reassurance based on sound evidence. The patient may not have any specific concerns or fears. Regardless the clinician should fully reassure the patient that serious causes of neck pain are rare and can be recognised on clinical assessment, and common causes are not threatening and have a good prognosis.

Reassure the patient that the severity of pain is greater than the amount of tissue injury. If there is imaging available that shows degenerative changes, reassure the patient that these abnormalities are commonly found in asymptomatic people, and that they will have been present long before the pain onset.

The clinician should be truthful that in the majority of cases no one knows what causes the pain, that it is probably something simple like a sprain or sore muscles, but that there is no simple way to make an exact diagnosis. Explain that even without treatment most patients recover, and that the most effective treatment is a tincture of time. However offer other measures as below to help the process along.

Activation

Encourage the patient to maintain activity as near to normal as possible. This is critical for preventing disability. Identify any barriers to achieving this, and be prepared to suggest alternative ways of maintaining activity levels if pain impedes this. Reassure the patient that there is no injury that will be worsened by resuming activity, and no injury that requires rest. Explain that rest can leads to stiffness and that the neck should be allowed to heal in a way that allows normal function. Resuming activities reminds the neck what is expected of it. In some cases there will need to be goal setting in that the patient should start with a short time engaged in activity and gradually progress the length of engagement. Other interventions may be used to reduce pain to allow activation.

One study found no benefit to work-site ergonomic intervention for spinal pain.[5] While there is often a discussion around posture in the consultation, the notion of there being an "optimal" posture is not supported by the evidence for improving outcomes. A common description of a neutral posture is sitting straight with the top of the head tall, chin slightly tilted down, shoulders down, the scapula retracted and depressed, regular diaphragmatic breathing, screen at neutral eye level, and elbows at 90 degrees. While the "bad" posture is often described as elevation and rounding of the shoulders, craning the neck forward, and intermittent breath-holding. The counter argument to a single neutral posture, is that frequent position changes allows changes in joint position, muscle length, and blood flow to the cervical spine. Patients should probably limit prolonged activities including sitting, telephone use, and fine motor handwork. Patients who sit for prolonged periods at work should get up frequently throughout the day and move their neck. If patients carry heavy equipment then this may need to be addressed.

Adjusting the patients sleep position may be helpful in some cases. Encourage the patient to have their head and neck be aligned with the rest of their body. For back sleepers, ask the patient to try sleeping with their thighs elevated on pillows and a small pillow under their head and neck. For side sleepers, it may be beneficial to use a larger pillow or multiple pillows to maintain cervical spine alignment. Try rolling up a hand-towel and placing it inside the pillow case to create an edge that matches the curve of the neck. In those with radicular pain avoid cervical extension.

Outside of work and sleep there may be other factors that can be modified. For example if the patient struggles to turn their head while driving encourage the use of mirrors. If hanging up the washing is problematic, then recommend that the patient hang the washing down by lowering the clothes line or standing on a stool.

Simple Exercises

Exercises for keeping the neck moving may be the single most effective measure for treatment of acute neck pain. They encourage resumption of normal activities, they have a therapeutic measure, and they are an active rather than passive modality that allows patients to become active participants in their own care. Patients are empowered to be the vehicles for their own recovery, and treatment can be applied when convenient. The patient should engage in the exercises at certain times of the day. Timing can be attached to other activities such as meal times, getting up in the morning, and going to bed at night. The objective is to increase and maintain mobility rather than strengthening the muscles or treating a specific lesion. Encourage the patient to warm up their neck prior to the exercises for example with a wheat bag, hot water bottle, hot shower or bath.

There are a couple of New Zealand publications that can be helpful

- McKenzie RA. Treat your own Neck. Spinal Publications, Waikanae, New Zealand, 1983.

- Mulligan B. Self treatments for back, neck and limbs. Plane View Services, Wellington, 2012.

An example of a home exercise program done with 10-15 repetitions as tolerated 2-4 times daily:

- Neck rotation - Turn the head to the side and provide slight overpressure for a few seconds, repeat on the other side.

- Neck lateral flexion – Tilt the head to the side, try to touch the ear to the shoulder, and apply slight overpressure for a few seconds. Repeat on the other side..

- Neck flexion – Seated or supine, bring the chin down to the chest with the out-breath, hold for a few seconds.

- Shoulder rolls – Seated, slowly swing the arms backwards and try to bring the scapulae together. Then swing them forward. Repeat in a rhythmic motion.

- Scapular retraction – Seated, position the head in a neutral position, and bring the shoulders and scapulae backwards. Hold the position for 10 seconds.

- Deep neck flexor strengthening – Supine, draw the chin down and inwards actively contracting the anterior neck muscles. Hold for five seconds.

- Anterior chest wall stretches – Standing in a doorway, abduct the arms and place the elbows against the door frame slightly lower than shoulder height. Lean forward to create a stretch of the anterior shoulder and chest muscles. Hold for 10-30 seconds.

Alternatively if the clinician does not have sufficient knowledge or experience to teach exercises, then they may wish to refer them to a colleague or allied health provider. The referral should be for active treatment modalities rather than passive therapy.

Follow up can be offered to check compliance and understanding. The patient may wish to continue the exercises after pain resolution, but there is no evidence to support this recommendation.

Clinical Review

Early review should be offered if the patient is distressed. And if not then review may be warranted following a week or so, however if they are recovering then this may not be required. There may be financial barriers to review. At review check understanding and compliance and reinforce recommendations. The patient may not be recovering due to lack of understanding.

If the prescribed interventions are not effective at all or are not sufficiently effective then consider multimodal therapy. Multimodal therapy is a combination of exercises and manual therapy guided by a therapist.

There may be other barriers to recovery such as personal, social, or occupational barriers. There may be barriers that can be addressed for example by referral to a psychologist or occupational therapist - however there may be financial barriers.

The patient and practitioner should persist with the recommended interventions for two months. Patients will usually recover in this period if they are going to do so. The patient may be showing significant signs of recovery and so in that case it may be wise to persist with the interventions. At three months they are classified as having chronic pain, and so between the two to three month mark the practitioner should consider organising onward referral to allow timely assessment.

Analgesia

There is no evidence that any specific analgesic is effective for acute neck pain. The Australian Acute Musculoskeletal Pain Guidelines recommend the use of paracetamol, but this is based on consensus. NSAIDs have not been shown to be more effective than paracetamol, and compound analgesics (paracetamol plus codeine) are only marginally better than paracetamol alone. Opioids are not generally recommended.

Prognosis

Most bouts of acute neck pain resolve within two months. However, many continue to have low grade symptoms or recurrence.[6] For example, in one general practice study, at one year 76% were fully recovered or much improved, but 47% continued to have ongoing neck pain.[7]

Early treatment does not improve prognosis. There is also no association between degenerative changes and prognosis.

Risk factors for developing chronic pain are being female, older age, radiculopathy, higher baseline pain, widespread pain, smoking, obesity, poor general health, and various psychosocial factors.

Resources

Bibliography

- Bogduk, Nikolai, and Brian McGuirk. Management of acute and chronic neck pain : an evidence-based approach. Edinburgh New York: Elsevier, 2006.

- ↑ Hoving et al.. Manual therapy, physical therapy, or continued care by a general practitioner for patients with neck pain. A randomized, controlled trial. Annals of internal medicine 2002. 136:713-22. PMID: 12020139. DOI.

- ↑ Korthals-de Bos et al.. Cost effectiveness of physiotherapy, manual therapy, and general practitioner care for neck pain: economic evaluation alongside a randomised controlled trial. BMJ (Clinical research ed.) 2003. 326:911. PMID: 12714472. DOI. Full Text.

- ↑ Hoving et al.. Manual therapy, physical therapy, or continued care by the general practitioner for patients with neck pain: long-term results from a pragmatic randomized clinical trial. The Clinical journal of pain 2006. 22:370-7. PMID: 16691091. DOI.

- ↑ Driessen et al.. Cost-effectiveness of conservative treatments for neck pain: a systematic review on economic evaluations. European spine journal : official publication of the European Spine Society, the European Spinal Deformity Society, and the European Section of the Cervical Spine Research Society 2012. 21:1441-50. PMID: 22447407. DOI. Full Text.

- ↑ Grooten et al.. The effect of ergonomic intervention on neck/shoulder and low back pain. Work (Reading, Mass.) 2007. 28:313-23. PMID: 17522452.

- ↑ Cohen & Hooten. Advances in the diagnosis and management of neck pain. BMJ (Clinical research ed.) 2017. 358:j3221. PMID: 28807894. DOI.

- ↑ Vos et al.. Clinical course and prognostic factors in acute neck pain: an inception cohort study in general practice. Pain medicine (Malden, Mass.) 2008. 9:572-80. PMID: 18565009. DOI.