Cauda Equina Syndrome: Difference between revisions

No edit summary |

No edit summary |

||

| Line 1: | Line 1: | ||

{{partial}} | {{partial}} | ||

Cauda equina syndrome is a rare acute polyradiculopathy of the | {{condition | ||

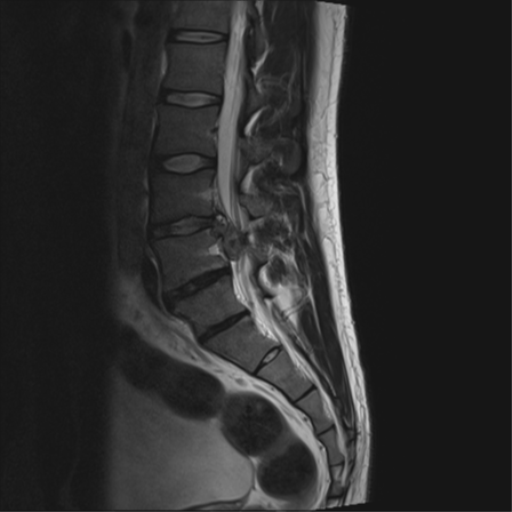

|image=Cauda-equina-syndrome T2 sagittal.png | |||

|name= | |||

|taxonomy= | |||

|synonym= | |||

|definition= | |||

|epidemiology=1-3% of all disc herniations, 1 case per 33,000-100,000. | |||

|causes=Most commonly massive central lumbar disc protrusion, amongst many other causes. | |||

|pathophysiology=Compression of the cauda equina | |||

|classification=CESS (cauda equina suspected), CESI (cauda equina incomplete), CESR (cauda equina with urinary retention). | |||

|primaryprevention= | |||

|secondaryprevention= | |||

|riskfactors=Obesity, spinal stenosis, recent lumbar spinal surgery. | |||

|history= | |||

|examination= | |||

|diagnosis= | |||

|tests=urgent MRI. | |||

|ddx= | |||

|treatment=Urgent decompression. | |||

|prognosis=Improved with earlier detection and treatment. | |||

}} | |||

Cauda equina syndrome is a rare acute polyradiculopathy of the descending lumbar and sacral nerve roots. It is caused by a lesion in the spinal canal that causes compression of the cauda equina, most commonly from a massive lumbar disc prolapse. It is a clinical syndrome with either unilateral or bilateral progressive lumbosacral polyradiculopathy, back pain, saddle anaesthesia, recent disturbance of bladder function, and sometimes disturbance of bowel function. The condition is a neurologic emergency that requires urgent MRI and surgical review. If left untreated the patient can develop permanent neurological deficits. | |||

==Anatomy and Embryology== | ==Anatomy and Embryology== | ||

| Line 13: | Line 35: | ||

Compression of the cauda equina can affected venous return to the cauda equina and sometimes interrupt the arterial supply. This leads to devitalised tissue and subsequently permanent loss of function of the territories supplied by the compressed nerve roots.<ref name="quaile"/> Lumbar disc herniation is the most common cause (45%), but anything that compresses the cauda equina can cause the syndrome including tumours, trauma, and infections.<ref name="Kapetanakis"/> There is an increased risk with obesity which is thought could be related to spinal epidural lipomatosis, reduced canal size, electrochemical behaviour, and inflammatory mediators.<ref name="quaile"/> | Compression of the cauda equina can affected venous return to the cauda equina and sometimes interrupt the arterial supply. This leads to devitalised tissue and subsequently permanent loss of function of the territories supplied by the compressed nerve roots.<ref name="quaile"/> Lumbar disc herniation is the most common cause (45%), but anything that compresses the cauda equina can cause the syndrome including tumours, trauma, and infections.<ref name="Kapetanakis"/> There is an increased risk with obesity which is thought could be related to spinal epidural lipomatosis, reduced canal size, electrochemical behaviour, and inflammatory mediators.<ref name="quaile"/> | ||

==Clinical | The list of causes of cauda equina syndrome are as follows:<ref name="bickle"/> | ||

*Degenerative causes: lumbar disc herniation (most common, especially at L4/5 and L5/S1), lumbar spinal canal stenosis, spondylolisthesis, haemorrhage into a Tarlov cyst, facet joint cysts | |||

*Inflammatory: both acute and chronic form may be seen in long-standing ankylosing spondylitis (2nd-5th decades; average 35 years), traumatic, spinal fracture or dislocation, epidural haematoma (may also be spontaneous, post-operative, post-procedural or post-manipulation) | |||

*Infective: arachnoiditis, epidural abscess, tuberculosis (Pott disease) | |||

*Tumours: primary, myxopapillary ependymoma, schwannoma, spinal meningioma, other tumours of the cauda equina, tumours in vertebral bodies, lymphoma, vertebral metastases, leptomeningeal carcinomatosis | |||

*Vascular: aortic dissection, arteriovenous malformation | |||

*Numerous other rare space-occupying lesions (e.g. sarcoid) | |||

==Clinical Presentation== | |||

{{Red flags| | {{Red flags| | ||

*Bilateral radiculopathy (sensory or motor disturbance) or radicular pain | *Bilateral radiculopathy (sensory or motor disturbance) or radicular pain | ||

| Line 24: | Line 54: | ||

<small>*White flags means surrender, i.e. the patient likely has irreversible cauda equina syndrome, and the diagnosis has been made too late{{#pmid:28637110|todd}}</small> | <small>*White flags means surrender, i.e. the patient likely has irreversible cauda equina syndrome, and the diagnosis has been made too late{{#pmid:28637110|todd}}</small> | ||

}} | }} | ||

Patients have a collection of symptoms. Clinical features can include low back pain, unilateral or bilateral radicular pain, reduced saddle region sensation, reduced sexual function, faecal incontinence, bladder dysfunction | |||

Patients have a collection of symptoms. Clinical features can include low back pain, unilateral or bilateral radicular pain and/or radiculopathy, reduced saddle region sensation, reduced sexual function, faecal incontinence, and bladder dysfunction. The onset of symptoms can be slow. Development of perineal dysfunction with bladder disturbance is commonly thought to be the onset of cauda equina syndrome. However the symptoms for cauda equina syndrome can be very non-specific. For example leg pain can be somatic referred rather than radicular, and cauda equina syndrome can occur with unilateral leg involvement. Urinary dysfunction can be due to pain inhibition rather than cauda equina compression.{{#pmid:30374638|quaile}} | |||

The physical examination should be thorough. The examination includes saddle area sensation testing and rectal examination for anal tone. However, it is imperative that normal anal tone is not a factor in whether to do MRI imaging, as this finding is insufficiently sensitive and does not correlate to MRI findings. Saddle anaesthesia has a high positive predictive value, but the absence of this cannot exclude the condition. Overall, it is not possible to exclude cauda equina syndrome on clinical assessment, and so urgent MRI imaging is necessary.<ref name="quaile"/> | The physical examination should be thorough. The examination includes saddle area sensation testing and rectal examination for anal tone. However, it is imperative that normal anal tone is not a factor in whether to do MRI imaging, as this finding is insufficiently sensitive and does not correlate to MRI findings. Saddle anaesthesia has a high positive predictive value, but the absence of this cannot exclude the condition. Overall, it is not possible to exclude cauda equina syndrome on clinical assessment, and so urgent MRI imaging is necessary.<ref name="quaile"/> | ||

| Line 43: | Line 74: | ||

==Investigations== | ==Investigations== | ||

MRI is the investigation of choice. MRI can assess for cauda equina compression, and determine the cause such as disc herniation, tumour, abscess, or haematoma. In the event of an absolute contraindication to MRI, other imaging options such as CT is necessary. The definition of what "urgent" does not have an accurate definition, and timing can depend on the context of where the patient is being cared for and the services available. Regardless, it should be done as soon as possible.<ref name="quaile"/> | MRI is the investigation of choice. MRI can assess for cauda equina compression, and determine the cause such as disc herniation, tumour, abscess, or haematoma. In the event of an absolute contraindication to MRI, other imaging options such as a CT myelogram is necessary. The definition of what "urgent" does not have an accurate definition, and timing can depend on the context of where the patient is being cared for and the services available. Regardless, it should be done as soon as possible.<ref name="quaile"/> Cauda equina syndrome is a clinical diagnosis, and therefore the correct terminology on MRI reporting is "compression of the cauda equina." For example, elderly patients with central canal stenosis may have compression of the cauda equina but not have cauda equina syndrome.<ref name="bickle">Ian Bickle and Henry Knipe et al. Cauda equina syndrome. Radiopaedia. Accessed 16/5/2021. [https://radiopaedia.org/articles/cauda-equina-syndrome?lang=gb Link]</ref> | ||

It is imperative that within a health service that there is a high rate of negative MRIs in order to reduce the rate of missing cases, and so there should be a low threshold for urgent imaging. Put another way, if there is a high rate of positive MRI findings then the health service is likely missing cases at their early stages. In the correct clinical context, cauda equina syndrome cannot be discounted without MRI imaging ruling out cauda equina compression.<ref name="todd"/> | It is imperative that within a health service that there is a high rate of negative MRIs in order to reduce the rate of missing cases, and so there should be a low threshold for urgent imaging. Put another way, if there is a high rate of positive MRI findings then the health service is likely missing cases at their early stages. In the correct clinical context, cauda equina syndrome cannot be discounted without MRI imaging ruling out cauda equina compression.<ref name="todd"/> | ||

Revision as of 18:11, 16 May 2021

Cauda equina syndrome is a rare acute polyradiculopathy of the descending lumbar and sacral nerve roots. It is caused by a lesion in the spinal canal that causes compression of the cauda equina, most commonly from a massive lumbar disc prolapse. It is a clinical syndrome with either unilateral or bilateral progressive lumbosacral polyradiculopathy, back pain, saddle anaesthesia, recent disturbance of bladder function, and sometimes disturbance of bowel function. The condition is a neurologic emergency that requires urgent MRI and surgical review. If left untreated the patient can develop permanent neurological deficits.

Anatomy and Embryology

The spinal cord runs from the medulla oblongata to the level of T12-L1. The next caudal part of the spinal cord is the medullary cone. The cauda equina starts from the medullary cone and consists of the spinal nerves L2-L5, S1-S5, and the coccygeal nerve. These nerves are comprised of dorsal (sensory) and ventral (motor) nerve roots. The nerve root functions include sensory supply to the saddle region, voluntary control of the outer surface of the rectum, voluntary control of the urinary sphincters, and the sensory and motor innervation of the lower limbs. Dysfunction of the cauda equina can cause problems in the above functions. The cauda equina is situated in the thecal sac and is surrounded by cerebrospinal fluid in the subarachnoid space.[1]

The cauda equina starts forming in the third month of gestation, and the spinal cord extends the entire length of the body at this time. After this time, the verebtral column bones and cartilage grows faster than the spinal cord. This causes the nerves below the cervical spine to follow a slanted path. The lumbar and sacral nerves therefore move caudally and vertically inside the spinal canal, before exiting through the intervertebral foramina. The nerve roots below L1 form the cauda equina.[1]

Epidemiology

The syndrome occurs in 1-3% of all disc herniations. The prevalence is one case per 33,000-100,000 [1]

Aetiopathophysiology

Compression of the cauda equina can affected venous return to the cauda equina and sometimes interrupt the arterial supply. This leads to devitalised tissue and subsequently permanent loss of function of the territories supplied by the compressed nerve roots.[2] Lumbar disc herniation is the most common cause (45%), but anything that compresses the cauda equina can cause the syndrome including tumours, trauma, and infections.[1] There is an increased risk with obesity which is thought could be related to spinal epidural lipomatosis, reduced canal size, electrochemical behaviour, and inflammatory mediators.[2]

The list of causes of cauda equina syndrome are as follows:[3]

- Degenerative causes: lumbar disc herniation (most common, especially at L4/5 and L5/S1), lumbar spinal canal stenosis, spondylolisthesis, haemorrhage into a Tarlov cyst, facet joint cysts

- Inflammatory: both acute and chronic form may be seen in long-standing ankylosing spondylitis (2nd-5th decades; average 35 years), traumatic, spinal fracture or dislocation, epidural haematoma (may also be spontaneous, post-operative, post-procedural or post-manipulation)

- Infective: arachnoiditis, epidural abscess, tuberculosis (Pott disease)

- Tumours: primary, myxopapillary ependymoma, schwannoma, spinal meningioma, other tumours of the cauda equina, tumours in vertebral bodies, lymphoma, vertebral metastases, leptomeningeal carcinomatosis

- Vascular: aortic dissection, arteriovenous malformation

- Numerous other rare space-occupying lesions (e.g. sarcoid)

Clinical Presentation

- Bilateral radiculopathy (sensory or motor disturbance) or radicular pain

- Progressive neurological deficits in the legs

- Difficulties in micturition (including impaired bladder or urethral sensation, hesitancy, poor stream)

- Urgency of micturition with preserved control of micturition

- Subjective and/or objective loss of perineal sensation

- Possible red or white flags*: Impaired perineal sensation, Impaired anal tone

- White flags*: Urinary retention or incontinence, faecal incontinence, perineal anaesthesia

*White flags means surrender, i.e. the patient likely has irreversible cauda equina syndrome, and the diagnosis has been made too late[4]

Patients have a collection of symptoms. Clinical features can include low back pain, unilateral or bilateral radicular pain and/or radiculopathy, reduced saddle region sensation, reduced sexual function, faecal incontinence, and bladder dysfunction. The onset of symptoms can be slow. Development of perineal dysfunction with bladder disturbance is commonly thought to be the onset of cauda equina syndrome. However the symptoms for cauda equina syndrome can be very non-specific. For example leg pain can be somatic referred rather than radicular, and cauda equina syndrome can occur with unilateral leg involvement. Urinary dysfunction can be due to pain inhibition rather than cauda equina compression.[2]

The physical examination should be thorough. The examination includes saddle area sensation testing and rectal examination for anal tone. However, it is imperative that normal anal tone is not a factor in whether to do MRI imaging, as this finding is insufficiently sensitive and does not correlate to MRI findings. Saddle anaesthesia has a high positive predictive value, but the absence of this cannot exclude the condition. Overall, it is not possible to exclude cauda equina syndrome on clinical assessment, and so urgent MRI imaging is necessary.[2]

There are three main clinical pictures of cauda equina lesions in adults, described below. In children, disc lesions are exceptionally rare below 15 years of age.[5]

Lateral Cauda Equina Syndrome

Neurofibroma is the most frequent cause, and high disc lesions are a rarer cause. The clinical features include anterior thigh pain, quadriceps wasting, weakness of foot inversion (L4 root lesion), and an absent knee jerk. With very high lesions that lie lateral to the terminal spinal cord, there may be pyramidal signs below the lesion. In this case there may be very brisk ankle jerks, ankle clonus, and an extensor plantar response. In this context, any sphincter compromise is likely a result of the cord compression.[5]

Midline Cauda Equina Lesions from Within

This is also called a conus lesion. The most common causes are ependymomas, dermoid tumours, and lipomas of the terminal cord. The roots are damaged from the inside, that is from S5 to S4 to S3 etc. In the early stages clinical features include rectal and genital pain, urination problems, and erectile dysfunction, but with no clear physical signs except if the perianal sensation (saddle anaesthesia) and anal reflex are tested carefully. Later clinical features include reduced ankle jerks and weakness of L5 and S1 myotomes. For ependymomas, the patient may have a 5 year history of a dull backache.[5]

Midline Cauda Equina Lesions From Outside

This is characterised by bilateral lumbar and sacral root lesions. If the patient has pain in unusual dermatomes such as L2, L3, S2, or S3, then the clinician should be suspicious. Pain in an L4, L5, or S1 region on the other hand is usually due to disc disease, but further imaging may still be required to exclude other pathology. Sinister causes include primary sacral bone tumours (chordomas), metastatic disease (especially prostate), reticulosis, leukaemia, direct seeding from malignant tumours in the CNS (medulloblastomas, ependymomas, pinealomas).[5]

Definitions

- Cauda equina syndrome suspected (CESS) - for example bilateral radiculopathy, or subtle features.

- Cauda equina syndrome incomplete (CESI) - there is objective evidence of cauda equina syndrome but the patient still has voluntary control of urination. There may be other urination problems such as urgency, poor stream, hesitancy, and/or reduced bladder or urethral sensation, and may rely on external pressure for voiding.

- Cauda equina syndrome with retention (CESR) - there is complete urinary retention and overflow incontinence. [4]

Investigations

MRI is the investigation of choice. MRI can assess for cauda equina compression, and determine the cause such as disc herniation, tumour, abscess, or haematoma. In the event of an absolute contraindication to MRI, other imaging options such as a CT myelogram is necessary. The definition of what "urgent" does not have an accurate definition, and timing can depend on the context of where the patient is being cared for and the services available. Regardless, it should be done as soon as possible.[2] Cauda equina syndrome is a clinical diagnosis, and therefore the correct terminology on MRI reporting is "compression of the cauda equina." For example, elderly patients with central canal stenosis may have compression of the cauda equina but not have cauda equina syndrome.[3]

It is imperative that within a health service that there is a high rate of negative MRIs in order to reduce the rate of missing cases, and so there should be a low threshold for urgent imaging. Put another way, if there is a high rate of positive MRI findings then the health service is likely missing cases at their early stages. In the correct clinical context, cauda equina syndrome cannot be discounted without MRI imaging ruling out cauda equina compression.[4]

Bladder volume scanning can be useful for detecting urinary retention. However a normal bladder scan does not exclude cauda equina syndrome, and this occurs in 40-60% of cases.[2]

Diagnosis

Cauda equina syndrome is a clinical rather than radiological diagnosis, but MRI can inform which patients with the clinical syndrome have cauda equina compression. The symptoms and signs are non-specific. Clinical features with the highest predictive value, for example painless urinary retention, are features of late often irreversible disease. The emphasis is on symptoms that are severe and progressive.[4] It is important to document the time of onset of bladder dysfunction because this is an important measure with respects to treatment and potential medicolegal assessments.[2]

Treatment

Cauda equina syndrome is a neurological emergency. It is imperative that the condition is recognised and decompressive surgery occurs before the onset of CESR if possible. Surgery should be extensive to allow complete decompression of the cauda equina. However this can be difficult where there is stretching of the thecal sac over a massive central disc prolapse. The presence of bladder function before decompression, and decompression before 48 hours are factors associated with improved outcomes.[2]

Patients treated at the point of CESS with bilateral radicular pain or bilateral radiculopathy are at risk of cauda equina syndrome from a central disc prolapse but do not have the syndrome at that point in time. Good outcomes are achieved if decompressive surgery is performed.[4]

If treated at the stage of CESI with incomplete clinical features, there is a reduced chance of developing more severe disease with painless urinary retention. The longterm bladder function is good, but there may be some symptoms of urgency or other symptoms that don't require catheterisation. There may be longterm sexual dysfunction if there was genital sensory loss prior to treatment. However overall good outcomes are seen with decompressive surgery for most patients.[4] The data available indicate poorer outcomes with longer delays to treatment for CESI, and a delay longer than 48 hours leads to poorer outcomes.[2]

If treated at the point of CESR with urinary retention, many patients have permanent severe impairment of cauda equina function with a paralysed insensate bladder and bowel that requires intermittent self-catheterisation, manual evacuation of faeces and/or bowel irrigation, and generally no significant sexual function. Only a small proportion of patients with severe deficits return to work. The timing of surgery after CESR develops is controversial, and recovery of function is more likely if there is some perineal sensation preoperatively.[4] There is unlikely to be improvement in CESR after 48 hours.[4]

There is no single symptom or sign of combination thereof that has a strong positive predictive value for diagnosing cauda equina syndrome before it is irreversible. Many of the red flags are subjective. It can be difficult to detect subtle perianal sensory deficits. Anal tone can also be difficult to interpret, and there is poor interobserver reliability.[4]

References

- ↑ 1.0 1.1 1.2 1.3 Kapetanakis et al.. Cauda Equina Syndrome Due to Lumbar Disc Herniation: a Review of Literature. Folia medica 2017. 59:377-386. PMID: 29341941. DOI.

- ↑ 2.0 2.1 2.2 2.3 2.4 2.5 2.6 2.7 2.8 Quaile. Cauda equina syndrome-the questions. International orthopaedics 2019. 43:957-961. PMID: 30374638. DOI.

- ↑ 3.0 3.1 Ian Bickle and Henry Knipe et al. Cauda equina syndrome. Radiopaedia. Accessed 16/5/2021. Link

- ↑ 4.0 4.1 4.2 4.3 4.4 4.5 4.6 4.7 4.8 Todd. Guidelines for cauda equina syndrome. Red flags and white flags. Systematic review and implications for triage. British journal of neurosurgery 2017. 31:336-339. PMID: 28637110. DOI.

- ↑ 5.0 5.1 5.2 5.3 Patten, John. Neurological differential diagnosis. London New York: Springer, 1996.

Literature Review

- Reviews from the last 7 years: review articles, free review articles, systematic reviews, meta-analyses, NCBI Bookshelf

- Articles from all years: PubMed search, Google Scholar search.

- TRIP Database: clinical publications about evidence-based medicine.

- Other Wikis: Radiopaedia, Wikipedia Search, Wikipedia I Feel Lucky, Orthobullets,