Cervical Intervertebral Discs: Difference between revisions

No edit summary |

No edit summary |

||

| Line 1: | Line 1: | ||

{{stub}} | {{stub}} | ||

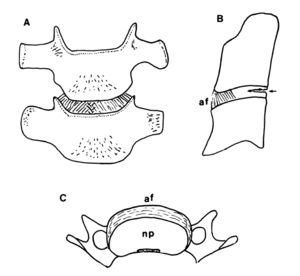

[[File:Cervical disc illustration.png|thumb|A: anterior view, showing inverted "V" of anterior anulus fibrosus. B: lateral view, showing anterior the anterior anulus and posterior transverse cleft. C: top view, showing lateral tapering of the anulus and posterior thin bundle of fibres '''©''' 2000 Elsevier<ref>{{#pmid:10946096}}</ref>]] | [[File:Cervical disc illustration.png|thumb|A: anterior view, showing inverted "V" of anterior anulus fibrosus. B: lateral view, showing anterior the anterior anulus and posterior transverse cleft. C: top view, showing lateral tapering of the anulus and posterior thin bundle of fibres '''©''' 2000 Elsevier<ref name=":2">{{#pmid:10946096}}</ref>]] | ||

The cervical disc is not a small lumbar disc, but is structurally unique. | The cervical disc is not a small lumbar disc, but is structurally unique. | ||

| Line 9: | Line 9: | ||

At birth the nucleus pulposus is relatively small, but persists until the second decade. Following that it gradually disappears as it becomes fibrocartilage. This results in cervical discs being harder and drier than lumbar discs. <ref name=":1">Bogduk N. Degenerative joint disease of the spine. Radiol Clin North Am. 2012 Jul;50(4):613-28. doi: 10.1016/j.rcl.2012.04.012. PMID: 22643388.</ref> | At birth the nucleus pulposus is relatively small, but persists until the second decade. Following that it gradually disappears as it becomes fibrocartilage. This results in cervical discs being harder and drier than lumbar discs. <ref name=":1">Bogduk N. Degenerative joint disease of the spine. Radiol Clin North Am. 2012 Jul;50(4):613-28. doi: 10.1016/j.rcl.2012.04.012. PMID: 22643388.</ref> | ||

In degenerative change | In degenerative change cervical discs form internal cracks and fissures, and slowly develop fibrocartilaginous bulges and osteophytes. It is normal to have transverse fissures on the posterior aspects of the discs. These initially appear in childhood in the uncovertebral regions, and with age extend medially, finally forming transverse clefts by the third decade of life.<ref name=":1" /> These transverse fissures facilitate axial rotation.<ref name=":2" /> | ||

==References== | ==References== | ||

[[Category:Cervical Spine Anatomy]] | [[Category:Cervical Spine Anatomy]] | ||

Revision as of 16:41, 15 August 2021

The cervical disc is not a small lumbar disc, but is structurally unique.

The annulus is not concentric, but rather is only well developed at the anterior aspect. The collagen fibres form a thick crescentic mass anteriorly and taper laterally towards the uncinate processes. There also isn't the criss-cross pattern of collagen fibres like in the lumbar discs. Rather, the fibres converge upwards towards the anterior end of the upper vertebra. When viewed front-on, the annulus is shaped like an inverted "V", with the fibres converging towards the midline, and the apex of the V pointing to the axis of rotation. In essence, the cervical annulus is more like an anterior interosseous ligament and is not load bearing.[2]

Posteriorly there is only a thin layer of paramedian, vertically oriented collagen fibres. The posterior aspect of the disc is really only covered by the posterior longitudinal ligament.[2]

At birth the nucleus pulposus is relatively small, but persists until the second decade. Following that it gradually disappears as it becomes fibrocartilage. This results in cervical discs being harder and drier than lumbar discs. [3]

In degenerative change cervical discs form internal cracks and fissures, and slowly develop fibrocartilaginous bulges and osteophytes. It is normal to have transverse fissures on the posterior aspects of the discs. These initially appear in childhood in the uncovertebral regions, and with age extend medially, finally forming transverse clefts by the third decade of life.[3] These transverse fissures facilitate axial rotation.[1]

References

- ↑ 1.0 1.1 Bogduk & Mercer. Biomechanics of the cervical spine. I: Normal kinematics. Clinical biomechanics (Bristol, Avon) 2000. 15:633-48. PMID: 10946096. DOI.

- ↑ 2.0 2.1 Mercer & Bogduk. The ligaments and annulus fibrosus of human adult cervical intervertebral discs. Spine 1999. 24:619-26; discussion 627-8. PMID: 10209789. DOI.

- ↑ 3.0 3.1 Bogduk N. Degenerative joint disease of the spine. Radiol Clin North Am. 2012 Jul;50(4):613-28. doi: 10.1016/j.rcl.2012.04.012. PMID: 22643388.