Chronic Post-Traumatic Neck Pain: Difference between revisions

| Line 23: | Line 23: | ||

Cervical vertebral fractures are difficult to detect by conventional investigations. The majority involve the upper cervical vertebrae. Fracture patterns include fractures of the odontoid process, laminae and articular processes of C2, and fracture of the occipital condyles. | Cervical vertebral fractures are difficult to detect by conventional investigations. The majority involve the upper cervical vertebrae. Fracture patterns include fractures of the odontoid process, laminae and articular processes of C2, and fracture of the occipital condyles. | ||

A useful text on cervical spine pathology is James Taylor's The Cervical Spine: An atlas of normal anatomy and the morbid anatomy of ageing and injuries. | |||

==Clinical Assessment== | ==Clinical Assessment== | ||

Revision as of 17:21, 23 May 2021

Whiplash can occur in a motor vehicle accident or even during a fall. It is a compressive injury, not a flexion-extension or acceleration-deceleration injury. Following impact, the trunk is thrust upwards, against the inertia of the head. This causes compression into a sigmoid deformation of the cervical spine at about 110ms after impact. During the deformation, the lower cervical segments undergo abnormal rotation into extension. The anterior annulus fibrosis is strained, and the facet joints are impacted. Extension is completed as the base of the neck descends.[1]

Anatomy

- See also: Category:Cervical Spine Anatomy

The cervical disc are very different to lumbar discs. The annulus is non-concentric, and only well-developed in the anterior aspect of the disc. It is more of an interosseous ligament which is non-load bearing.

Epidemiology

Studies have consistently shown that the facet joints are implicated 50-60% of the time in chronic post-traumatic neck pain when identified via concordant comparative medial branch blocks.

The cervical disc is implicated 16% of the time when evaluated by provocative discography.[2]

Pathophysiology

Specific tissue damage seen are tears of the anterior anulus fibrosis, strain or tears of the facet joint capsules (rim lesions and avulsions), and impaction injuries of the facet joints. Impaction injuries include contusions of the intra-articular meniscoids with intra articular haemorrhage, and subchondral and transarticular fractures. [1]

Rim lesions are the most common disc injury. They are a horizontal annular tear at the vertebral rim, without tearing the anterior longitudinal ligament. They are often a multilevel injury. Anterior disc injuries vary from small rim lesions to partial avulsion of the anterior longitudinal ligament.

Disc avulsions are the separation of the disc from the vertebral body along the disc-vertebral junction. They are the most common severe disc injury in subjects under the age of 55 years. There is variable extent of anterior longitudinal ligament damage. The anterior muscles are usually left intact.

With acute zygapophyseal joint injuries there is often haemarthrosis. The bleeding can come from a ruptured synovial fold, damaged articular surface, or a zygapophyseal joint fracture. Haemarthrosis is often multi-level.

Other rare injuries attributed to whiplash, normally seen with more significant forces than seen with the above pathology, include disruption of alar ligaments, prevertebral haematoma, perforation of oesophagus, tears of the sympathetic trunk, damage to the recurrent laryngeal nerve, spinal cord injury, perilymph fistula, thrombosis or traumatic aneurysm of the vertebral or internal carotid arteries, anterior spinal artery syndrome, and cervical vertebral fracture.

Cervical vertebral fractures are difficult to detect by conventional investigations. The majority involve the upper cervical vertebrae. Fracture patterns include fractures of the odontoid process, laminae and articular processes of C2, and fracture of the occipital condyles.

A useful text on cervical spine pathology is James Taylor's The Cervical Spine: An atlas of normal anatomy and the morbid anatomy of ageing and injuries.

Clinical Assessment

History

Assess for red flags.

Examination

There is no proven diagnostic value in the physical examination. There is good reliability of tenderness over the facet joints, but it lacks validity. Testing for gross range of motion has not been tested for reliability and lacks validity. Provocation of neck pain with various movements may be seen but this is also not diagnostic of a specific pain source.

Investigations

Imaging

Imaging will often be normal or show "cervical spondylosis." This does not exclude a nociceptive source of pain. Osteoarthritis of the facet joints may be seen. Cervical degenerative disease refers to the combination of cervical spondylosis and facet joint osteoarthritis.

In general there is no link between cervical degenerative joint disease and pain. However, there is a slight clinical significance with degenerative disc (but not facet osteoarthritis) findings at the C5/6 level. There is also an association with marked (level 3) degenerative changes and neck pain.

CT scintigraphy is used a lot in New Zealand. It is good for picking up small occult fracture and tumours etc. It does not however show pain, only increased blood flow. It tends to miss cases where there is pain arising from soft tissue damage for example capsular tears.

Pathology like rim lesions, disc avulsions, and haemarthroses may or may not be seen if MRI is done soon after injury. In the subacute and chronic stage MRI may be normal, but the injury may still be clinically relevant and cause ongoing problems.

Medial Branch Blocks

- Main article: Cervical Facet Joint Precision Treatment

The two most common joints to be positive (by a long shot) are the C2-3 and C5-6 facet joints.[3]

- C1-2 (Atlanto-axial joint)

The C1-2 cannot be blocked by medial branch blocks. Therefore it is blocked via the lateral atlanto-axial joint block. This is potentially hazardous as it is close to the vertebral artery and dural sac. There is a very small risk of hitting the C2 nerve (~4%). The C2 ventral ramus is closely related to the posterior capsule of the lateral atlanto-axial joint, assumes a variable relationship to the cavity of the joint, some authors report that it runs exactly parallel to the line of the joint, while others illustrate it running below. Most often the nerve runs across the capsule, behind the superior articular process of C2, and less often behind the inferior articular process of C1. The variability means there is no guaranteed trajectory to avoid the C2 ventral ramus. The recommended technique is to place the needle on a bony target above or below the lateral aspect of the joint. This is to reduce the risk of hitting the dural sac, C2 dorsal ganglion, vertebral artery, and over-penetration. Once the needle hits bone, advance the needle very slowly.

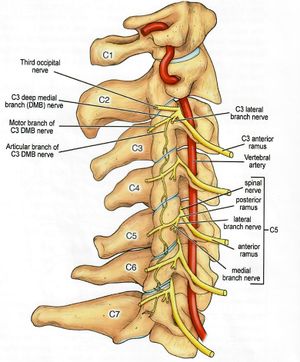

- C2-3 (Third occipital nerve)

This is the most useful diagnostic intervention for chronic cervicogenic pain, because the C2-3 joint is the most common source of pain. There are two medial branches of the C3 dorsal ramus. There is the deep medial branch which contributes to the innervation of the C3-4 joint, and the superficial branch which is the third occipital nerve and innervates the C2-3 joint and also semispinalis capitis and a small area of skin in the suboccipital area. The nerve crosses the joint, but is quite variable in its distribution, and the needle placement reflects the variability, with three small volume injections along the distribution. It is easy to miss the nerve even if the needle locations are correct. Testing the expected patch of numbness is a good way of checking that you have anaesthetised the nerve. Injecting contrast can be helpful. Ultrasound guided injections can also be done.

- C3-4

This is an uncommon source of pain on its own.

Provocative Discography

Provocative discography is hardly ever done in New Zealand. There is a very high false positive rate. Discography should never been done unless medial branch blocks have been done and are negative. Even though C5/6 has the highest incidence of degenerative change, there are still high rates of positive discs at other levels. C3/4, C4/5, and C5/6 are the most common with similar incidences of positive tests.

The diagnosis of cervical discogenic pain can be made when all the following criteria are met:

- Cervical facet joint pain has been excluded with medial branch blocks

- Disc stimulation has been performed with correct technique

- Disc stimulation reproduces concordant pain

- Disc stimulation reproduces pain of at least 7/10 in intensity

- Disc stimulation of adjacent discs does not reproduce pain.

Discitis is a a rare risk at just under 1%.

Prognosis

There is good recovery after the first year, but then it tails off. At 24 months 14% have not fully recovered, and 4% are severely affected.[4]

Important Artciles

References

- ↑ 1.0 1.1 Bogduk. On cervical zygapophysial joint pain after whiplash. Spine 2011. 36:S194-9. PMID: 22020612. DOI.

- ↑ Yin & Bogduk. The nature of neck pain in a private pain clinic in the United States. Pain medicine (Malden, Mass.) 2008. 9:196-203. PMID: 18298702. DOI.

- ↑ Cooper et al.. Cervical zygapophysial joint pain maps. Pain medicine (Malden, Mass.) 2007. 8:344-53. PMID: 17610457. DOI.

- ↑ Radanov et al.. Long-term outcome after whiplash injury. A 2-year follow-up considering features of injury mechanism and somatic, radiologic, and psychosocial findings. Medicine 1995. 74:281-97. PMID: 7565068. DOI.

- Kaneoka, K., Ono, K., Inami, S., Ochiai, N., & Hayashi, K. (2002). The Human Cervical Spine Motion During Rear-Impact Collisions. Journal of Whiplash & Related Disorders, 1(1), 85–97. doi:10.3109/j180v01n01_08

- Kaneoka et al.. Motion analysis of cervical vertebrae during whiplash loading. Spine 1999. 24:763-9; discussion 770. PMID: 10222526. DOI.