Medical History: Difference between revisions

(Created page with "The process of diagnostic reasoning starts with the medical history. The validity of the history is highly dependent on the mastery of the relevant content, more so than a gen...") |

No edit summary |

||

| Line 1: | Line 1: | ||

The process of diagnostic reasoning starts with the medical history. The validity of the history is highly dependent on the mastery of the relevant content, more so than a general diagnostic strategy. Expert clinicians focus more on relevant information, and are highly selective in their use of the retrieved data. | The process of diagnostic reasoning starts with the medical history. The validity of the history is highly dependent on the mastery of the relevant content, more so than a general diagnostic strategy. Expert clinicians focus more on relevant information, and are highly selective in their use of the retrieved data. The medical history is complemented by the [[Musculoskeletal Examination Principles|physical examination]]. | ||

Other than the utility in the process of diagnostic reasoning, the history is used to elicit patient ideas (how they perceive their situation), concerns (what they are worried about), and expectations (what they hope to get out of the consultation). | Other than the utility in the process of diagnostic reasoning, the history is used to elicit patient ideas (how they perceive their situation), concerns (what they are worried about), and expectations (what they hope to get out of the consultation). It lays the foundation for the clinician-patient relationship. | ||

== Traditional vs Chief Complaint Driven Medical History == | == Traditional vs Chief Complaint Driven Medical History == | ||

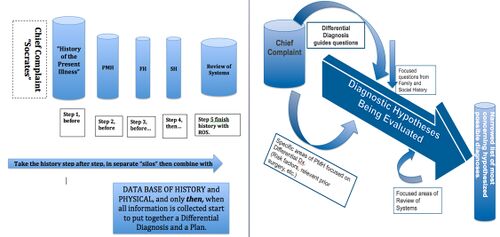

[[File:Traditional vs Chief complaint history taking.jpg|thumb|500x500px|Traditional (left) vs Chief Complaint Driven (right) methods of history taking.<ref>Nierenberg R, 2020, 'Using the Chief Complaint Driven Medical History: Theoretical Background and Practical Steps for Student Clinicians ', ''MedEdPublish'', 9, [1], 17, <nowiki>https://doi.org/10.15694/mep.2020.000017.1</nowiki></ref>]] | [[File:Traditional vs Chief complaint history taking.jpg|thumb|500x500px|Traditional (left) vs Chief Complaint Driven (right) methods of history taking.<ref name=":0">Nierenberg R, 2020, 'Using the Chief Complaint Driven Medical History: Theoretical Background and Practical Steps for Student Clinicians ', ''MedEdPublish'', 9, [1], 17, <nowiki>https://doi.org/10.15694/mep.2020.000017.1</nowiki></ref>]] | ||

The traditional method of obtaining a medical history follows a sequential series of 'siloed' categories of information. It starts with the presenting complaint, moves on to the history of presenting complaint (e.g. SOCRATES mnemonic for pain), past medical history, family history, social history, and review of systems. Once all the data is gathered only then is everything integrated. | The traditional method of obtaining a medical history follows a sequential series of 'siloed' categories of information. It starts with the presenting complaint, moves on to the history of presenting complaint (e.g. SOCRATES mnemonic for pain), past medical history, family history, social history, and review of systems. Once all the data is gathered only then is everything integrated. | ||

Expert clinicians tend to rather follow a chief complaint driven history taking. The chief or presenting complaint immediately generates a list of diagnostic possibilities. The clinician then constantly | Expert clinicians tend to rather follow a chief complaint driven history taking. The chief or presenting complaint immediately generates a list of diagnostic possibilities, in fact the most important determinant of whether the correct diagnosis was reached is if that diagnosis was on the initial list of possible diagnoses.<ref>Mandin, H., Jones, A., Woloschuk, W. and Harasym, P. (1997) ‘Helping students learn to think like experts when solving clinical problems’, ''Academic Medicine, 72, ''pp. 173-179. <nowiki>https://doi.org/10.1097/00001888-199703000-00009</nowiki> </ref> The clinician then constantly generates and tests hypotheses and in doing so is simultaneously problem solving as they elicit the history. The clinician selects a small number of elements from areas of the history as needed to either support or refute different hypotheses, forming the pertinent positives and negatives. In this manner, each question is a test. The selected elements are often dichotomous and exist within the context of the [[Diagnostic Schema|diagnostic schemas]] and [[Illness Scripts|illness scripts]] in the mind of the clinician, which may occur as a [[Dual Process Theory|fast or slow process]]. | ||

An example of how the traditional approach is not used by expert clinicians is acute knee pain. A key question here in the diagnostic schema is going to be a history of trauma. In the setting of trauma other key questions may include the mechanism and a history of swelling. A skiing injury is going to put the possibility of internal knee derangement high on the list of possibilities and subsequent questions may be directed at that. With a lack of trauma, some key questions may include a history swelling and fever, and a past medical history of osteoarthritis and gout. If a Pacific Islander presents with an obviously hot and swollen knee, the first question is probably going to be whether there is a past history of gout. | The key differentiating factor between novices and experts is knowledge. Clinical reasoning is not simply a general process of problem solving, but is dependent on knowledge in that specific domain, requires specific cognitive processes for specific tasks, and is also experience specific. Strategy is less important than mastery of the content.<ref name=":0" /> | ||

An example of how the traditional approach is not used by expert clinicians is acute knee pain. A key question here in the diagnostic schema is going to be a history of trauma. In the setting of trauma other key questions may include the mechanism and a history of swelling. A skiing injury is going to put the possibility of internal knee derangement high on the list of possibilities and subsequent questions may be directed at that. With a lack of trauma, some key questions may include a history swelling and fever, and a past medical history of osteoarthritis and gout. Contextual factors are also important. If a Pacific Islander presents with an obviously hot and swollen knee, the first question is probably going to be whether there is a past history of gout. | |||

== Traditional Comprehensive Medical History == | |||

One important aspect in history taking is for the doctor to be cognizant of "red flag" clinical features that raise concern for serious pathology such as infection or neoplasia. Red flags should be assessed at the initial encounter and at every subsequent encounter. | |||

There are nine domains in the comprehensive medical history | |||

* '''''identification''''' | |||

* '''''presenting symptom(s)''''' | |||

* '''''history of the index condition (history of presenting or chief complaint)''''' | |||

* '''''intercurrent conditions''''' | |||

* '''''intercurrent medical treatment''''' | |||

* '''''general medical history''''' | |||

* '''''systems review''''' | |||

* '''''psychological history''''' | |||

* '''''social history''''' | |||

One view of goal of medical history taking is to obtain information that will help to provide effective treatment, i.e. treatment that will produce a better outcome than can be expected from the natural history. This view, which can be reformulated as a diagnosis having only "positive therapeutic utility" is clearly an incomplete view. Many conditions don't need treatment, and a diagnosis alone is all that is sufficient, i.e. there is simply a "diagnostic utility". For example precordial catch syndrome, non-painful slipping ribs, or non-painful clicking joints. Furthermore many conditions don't have a treatment, and a diagnosis is all that can be provided, and it may stop further unnecessary treatment. This can be reframed as "negative therapeutic utility." | |||

The history of presenting complaint | |||

The '''history of the presenting complaint''' is explored systematically in the traditional approach to medical history taking. There are fourteen specific aspects: | |||

* '''''site''''' | |||

* '''''distribution''''' | |||

* '''''quality''''' | |||

* '''''duration''''' | |||

* '''''periodicity''''' | |||

* '''''intensity''''' | |||

* '''''aggravating factors''''' | |||

* '''''relieving factors''''' | |||

* '''''effects on activities of daily living''''' | |||

* '''''associated symptoms onset''''' | |||

* '''''previous similar symptoms''''' | |||

* '''''previous treatment''''' | |||

* '''''current treatment''''' | |||

== Reliability and Validity == | |||

In the musculoskeletal setting, there is unfortunately little data on the reliability and validity of items in the medical history. | |||

Reliability: One study on patients with longstanding shoulder pain found that only 15/23 items on history had moderate interobserver [[reliability]] (kappa > 0.4), with 6/23 having good reliability (kappa >0.6).<ref>Nørregaard J, Krogsgaard MR, Lorenzen T'', et al'' Diagnosing patients with longstanding shoulder joint pain ''Annals of the Rheumatic Diseases'' 2002;'''61:'''646-649.</ref> | |||

Validity: A systematic review of hip osteoarthritis found that only medial thigh pain had validity but this was a rare symptom.<ref>Metcalfe, David et al. “Does This Patient Have Hip Osteoarthritis?: The Rational Clinical Examination Systematic Review.” ''JAMA'' vol. 322,23 (2019): 2323-2333. doi:10.1001/jama.2019.19413</ref> On back pain, one study showed poor overall validity.<ref>''Deyo RA, Rainville J, Kent DL. What can the history and physical examination tell us about low back pain? JAMA 1992; 268: 760-765.''</ref> Another found that the most useful features for predicting malignancy in back pain were past history of malignancy (LR+ 15.5), failure to improve with treatment (LR+ 3.1), and age over 50 (LR+ 2.7).<ref>''Deyo RA, Diehl AK. Cancer as a cause of back pain: frequency, clinical presentation and diagnostic strategies. J Gen Int Med 1988; 3: 230-238.''</ref> On rotator cuff tears, many historical feature had poor validity.<ref>''Litaker D, Pioro M, El Bilbeisi H, Brems J. Returning to the bedside: using the history and physical examination to identify rotator cuff tears. J Am Geriatr Soc 2000; 48:1633-1637.''</ref> | |||

== See Also == | == See Also == | ||

| Line 16: | Line 60: | ||

== References == | == References == | ||

[[Category:Clinical Reasoning]] | [[Category:Clinical Reasoning]] | ||

<references /> | |||

[[Category:Communication]] | |||

Revision as of 11:11, 28 August 2021

The process of diagnostic reasoning starts with the medical history. The validity of the history is highly dependent on the mastery of the relevant content, more so than a general diagnostic strategy. Expert clinicians focus more on relevant information, and are highly selective in their use of the retrieved data. The medical history is complemented by the physical examination.

Other than the utility in the process of diagnostic reasoning, the history is used to elicit patient ideas (how they perceive their situation), concerns (what they are worried about), and expectations (what they hope to get out of the consultation). It lays the foundation for the clinician-patient relationship.

Traditional vs Chief Complaint Driven Medical History

The traditional method of obtaining a medical history follows a sequential series of 'siloed' categories of information. It starts with the presenting complaint, moves on to the history of presenting complaint (e.g. SOCRATES mnemonic for pain), past medical history, family history, social history, and review of systems. Once all the data is gathered only then is everything integrated.

Expert clinicians tend to rather follow a chief complaint driven history taking. The chief or presenting complaint immediately generates a list of diagnostic possibilities, in fact the most important determinant of whether the correct diagnosis was reached is if that diagnosis was on the initial list of possible diagnoses.[2] The clinician then constantly generates and tests hypotheses and in doing so is simultaneously problem solving as they elicit the history. The clinician selects a small number of elements from areas of the history as needed to either support or refute different hypotheses, forming the pertinent positives and negatives. In this manner, each question is a test. The selected elements are often dichotomous and exist within the context of the diagnostic schemas and illness scripts in the mind of the clinician, which may occur as a fast or slow process.

The key differentiating factor between novices and experts is knowledge. Clinical reasoning is not simply a general process of problem solving, but is dependent on knowledge in that specific domain, requires specific cognitive processes for specific tasks, and is also experience specific. Strategy is less important than mastery of the content.[1]

An example of how the traditional approach is not used by expert clinicians is acute knee pain. A key question here in the diagnostic schema is going to be a history of trauma. In the setting of trauma other key questions may include the mechanism and a history of swelling. A skiing injury is going to put the possibility of internal knee derangement high on the list of possibilities and subsequent questions may be directed at that. With a lack of trauma, some key questions may include a history swelling and fever, and a past medical history of osteoarthritis and gout. Contextual factors are also important. If a Pacific Islander presents with an obviously hot and swollen knee, the first question is probably going to be whether there is a past history of gout.

Traditional Comprehensive Medical History

One important aspect in history taking is for the doctor to be cognizant of "red flag" clinical features that raise concern for serious pathology such as infection or neoplasia. Red flags should be assessed at the initial encounter and at every subsequent encounter.

There are nine domains in the comprehensive medical history

- identification

- presenting symptom(s)

- history of the index condition (history of presenting or chief complaint)

- intercurrent conditions

- intercurrent medical treatment

- general medical history

- systems review

- psychological history

- social history

One view of goal of medical history taking is to obtain information that will help to provide effective treatment, i.e. treatment that will produce a better outcome than can be expected from the natural history. This view, which can be reformulated as a diagnosis having only "positive therapeutic utility" is clearly an incomplete view. Many conditions don't need treatment, and a diagnosis alone is all that is sufficient, i.e. there is simply a "diagnostic utility". For example precordial catch syndrome, non-painful slipping ribs, or non-painful clicking joints. Furthermore many conditions don't have a treatment, and a diagnosis is all that can be provided, and it may stop further unnecessary treatment. This can be reframed as "negative therapeutic utility."

The history of presenting complaint

The history of the presenting complaint is explored systematically in the traditional approach to medical history taking. There are fourteen specific aspects:

- site

- distribution

- quality

- duration

- periodicity

- intensity

- aggravating factors

- relieving factors

- effects on activities of daily living

- associated symptoms onset

- previous similar symptoms

- previous treatment

- current treatment

Reliability and Validity

In the musculoskeletal setting, there is unfortunately little data on the reliability and validity of items in the medical history.

Reliability: One study on patients with longstanding shoulder pain found that only 15/23 items on history had moderate interobserver reliability (kappa > 0.4), with 6/23 having good reliability (kappa >0.6).[3]

Validity: A systematic review of hip osteoarthritis found that only medial thigh pain had validity but this was a rare symptom.[4] On back pain, one study showed poor overall validity.[5] Another found that the most useful features for predicting malignancy in back pain were past history of malignancy (LR+ 15.5), failure to improve with treatment (LR+ 3.1), and age over 50 (LR+ 2.7).[6] On rotator cuff tears, many historical feature had poor validity.[7]

See Also

References

- ↑ 1.0 1.1 Nierenberg R, 2020, 'Using the Chief Complaint Driven Medical History: Theoretical Background and Practical Steps for Student Clinicians ', MedEdPublish, 9, [1], 17, https://doi.org/10.15694/mep.2020.000017.1

- ↑ Mandin, H., Jones, A., Woloschuk, W. and Harasym, P. (1997) ‘Helping students learn to think like experts when solving clinical problems’, Academic Medicine, 72, pp. 173-179. https://doi.org/10.1097/00001888-199703000-00009

- ↑ Nørregaard J, Krogsgaard MR, Lorenzen T, et al Diagnosing patients with longstanding shoulder joint pain Annals of the Rheumatic Diseases 2002;61:646-649.

- ↑ Metcalfe, David et al. “Does This Patient Have Hip Osteoarthritis?: The Rational Clinical Examination Systematic Review.” JAMA vol. 322,23 (2019): 2323-2333. doi:10.1001/jama.2019.19413

- ↑ Deyo RA, Rainville J, Kent DL. What can the history and physical examination tell us about low back pain? JAMA 1992; 268: 760-765.

- ↑ Deyo RA, Diehl AK. Cancer as a cause of back pain: frequency, clinical presentation and diagnostic strategies. J Gen Int Med 1988; 3: 230-238.

- ↑ Litaker D, Pioro M, El Bilbeisi H, Brems J. Returning to the bedside: using the history and physical examination to identify rotator cuff tears. J Am Geriatr Soc 2000; 48:1633-1637.