Opioid Deprescribing: Difference between revisions

No edit summary |

No edit summary |

||

| Line 3: | Line 3: | ||

==Evidence== | ==Evidence== | ||

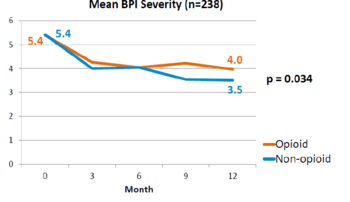

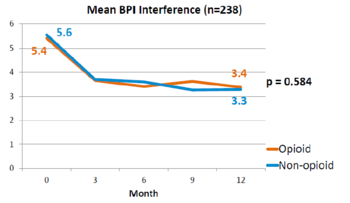

A landmark study was published in 2018 by Krebs et al - the SPACE study. It was a pragmatic randomised controlled trial comparing opioid versus non opioid analgesics for 12 months in primary care. Participants were 240 VA patients with moderate to severe chronic back pain or knee/hip OA, and not on opioids. The mean pain intensity initially was 5.4 in both arms. Pain scores at 1 year was worse in the opioid arm (4.0) than non opioid (3.5) (P=0.034). There was no difference in pain interference, and adverse effects were worse in opioid group (P=0.03).<ref name="SPACE"/> | A landmark study was published in 2018 by Krebs et al - the SPACE study. It was a pragmatic randomised controlled trial comparing opioid versus non opioid analgesics for 12 months in primary care. Participants were 240 VA patients with moderate to severe chronic back pain or knee/hip OA, and not on opioids. The mean pain intensity initially was 5.4 in both arms. Pain scores at 1 year was worse in the opioid arm (4.0) than non opioid (3.5) (P=0.034). There was no difference in pain interference, and adverse effects were worse in opioid group (P=0.03).<ref name="SPACE"/> | ||

<gallery mode="nolines" widths= | <gallery mode="nolines" widths=350px heights=250px> | ||

File:SPACE BPI 2018.png|Brief Pain Inventory (BPI) over 12 months | File:SPACE BPI 2018.png|Brief Pain Inventory (BPI) over 12 months | ||

File:SPACE BPI interference 2018.png|Pain Interference over 12 months | File:SPACE BPI interference 2018.png|Pain Interference over 12 months | ||

| Line 13: | Line 12: | ||

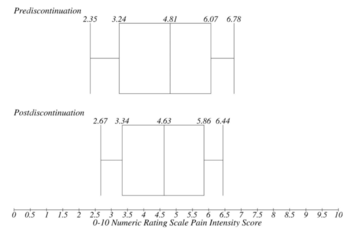

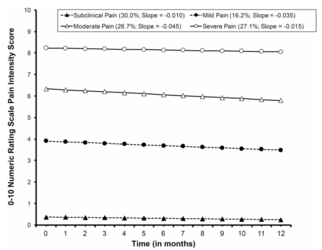

McPherson et al studied changes in pain intensity over 12 months after opioid discontinuation in chronic non-cancer pain. Participants were 551 VA patients, with 87% musculoskeletal pain, 11% headaches, and 6% neuropathic pain. Mean estimated pain at the time of opioid discontinuation was 4.9. There was no statistically significant decline in pain intensity over 12 months after discontinuation. Patients were statistically divided into four groups - no pain (average pain 0.37), mild pain (3.9), moderate pain (6.33), severe pain (8.23). Pain trajectories in each category were similar to the overall results. Patients with mild and moderate pain had the greatest pain reductions after discontinuation. On average, pain intensity after discontinuation did not worsen for patients, and many slightly improved.<ref name="McPherson"/> | McPherson et al studied changes in pain intensity over 12 months after opioid discontinuation in chronic non-cancer pain. Participants were 551 VA patients, with 87% musculoskeletal pain, 11% headaches, and 6% neuropathic pain. Mean estimated pain at the time of opioid discontinuation was 4.9. There was no statistically significant decline in pain intensity over 12 months after discontinuation. Patients were statistically divided into four groups - no pain (average pain 0.37), mild pain (3.9), moderate pain (6.33), severe pain (8.23). Pain trajectories in each category were similar to the overall results. Patients with mild and moderate pain had the greatest pain reductions after discontinuation. On average, pain intensity after discontinuation did not worsen for patients, and many slightly improved.<ref name="McPherson"/> | ||

<gallery mode="nolines" widths= | <gallery mode="nolines" widths=350px heights=250px> | ||

File:Opioid discontinuation mcpherson overall 2018.png|Pain over time | File:Opioid discontinuation mcpherson overall 2018.png|Pain over time | ||

File:Opioid discontinuation mcpherson 2018.png|Pain over time between groups | File:Opioid discontinuation mcpherson 2018.png|Pain over time between groups | ||

</gallery> | </gallery> | ||

==Guidelines== | |||

;FPM ANZCA 2015 | |||

Opioids cannot be considered a core component of CNCP management | |||

Traffic lights 40 & 100mg | |||

Given widespread prescription the following principles are offered... | |||

;BPAC NZ<ref>Understanding the role of opioids in chronic non-malignant pain. https://bpac.org.nz/2018/opioids-chronic.aspx</ref> | |||

There is no evidence that opioids are effective for treating chronic non-malignant pain | |||

Opioids are associated with significant adverse effects, and analgesic efficacy decreases with continuous use due to neuroadaptations that result in dependence, tolerance and opioid-induced hyperalgesia | |||

Improving or retaining function should be the goal of treatment for most patients with chronic non-malignant pain; regular use of potent opioids at high doses is contrary to this aim | |||

Pain is only one aspect of managing a patient with a chronic pain condition; attention to psychological and social factors is essential, along with acknowledging and empathising with the emotional wellbeing of the patient | |||

If long-term use of opioids cannot be avoided, intermittent dosing using the lowest possible potency and dose is preferable | |||

;US Centres for Disease Control & Prevention 2016 | |||

Non pharmacological & non opioid treatments preferred | |||

Traffic lights 50 and 90mg oMEDD | |||

Consider opioids only if expected benefits outweigh risks | |||

;UK National Institute for Health & Care Excellence. Guideline for LBP and sciatica 2016 | |||

Do not offer opioids for chronic low back pain | |||

==References== | ==References== | ||

<references/> | <references/> | ||

{{Reliable sources}} | {{Reliable sources}} | ||

[[Category:Partially complete articles]] | |||

[[Category:Pharmacology]] | [[Category:Pharmacology]] | ||

Revision as of 17:37, 3 April 2021

There is clear evidence that opioids are not effective for long term chronic non-cancer pain. In fact, patients are worse of in terms of pain levels with opioid use potentially due to opioid hyperalgesia. Furthermore opioid use has real harm.[1] Discontinuation does not cause any changes in pain intensity.[2]

Evidence

A landmark study was published in 2018 by Krebs et al - the SPACE study. It was a pragmatic randomised controlled trial comparing opioid versus non opioid analgesics for 12 months in primary care. Participants were 240 VA patients with moderate to severe chronic back pain or knee/hip OA, and not on opioids. The mean pain intensity initially was 5.4 in both arms. Pain scores at 1 year was worse in the opioid arm (4.0) than non opioid (3.5) (P=0.034). There was no difference in pain interference, and adverse effects were worse in opioid group (P=0.03).[1]

McPherson et al studied changes in pain intensity over 12 months after opioid discontinuation in chronic non-cancer pain. Participants were 551 VA patients, with 87% musculoskeletal pain, 11% headaches, and 6% neuropathic pain. Mean estimated pain at the time of opioid discontinuation was 4.9. There was no statistically significant decline in pain intensity over 12 months after discontinuation. Patients were statistically divided into four groups - no pain (average pain 0.37), mild pain (3.9), moderate pain (6.33), severe pain (8.23). Pain trajectories in each category were similar to the overall results. Patients with mild and moderate pain had the greatest pain reductions after discontinuation. On average, pain intensity after discontinuation did not worsen for patients, and many slightly improved.[2]

Guidelines

- FPM ANZCA 2015

Opioids cannot be considered a core component of CNCP management Traffic lights 40 & 100mg Given widespread prescription the following principles are offered...

- BPAC NZ[3]

There is no evidence that opioids are effective for treating chronic non-malignant pain Opioids are associated with significant adverse effects, and analgesic efficacy decreases with continuous use due to neuroadaptations that result in dependence, tolerance and opioid-induced hyperalgesia Improving or retaining function should be the goal of treatment for most patients with chronic non-malignant pain; regular use of potent opioids at high doses is contrary to this aim Pain is only one aspect of managing a patient with a chronic pain condition; attention to psychological and social factors is essential, along with acknowledging and empathising with the emotional wellbeing of the patient If long-term use of opioids cannot be avoided, intermittent dosing using the lowest possible potency and dose is preferable

- US Centres for Disease Control & Prevention 2016

Non pharmacological & non opioid treatments preferred Traffic lights 50 and 90mg oMEDD Consider opioids only if expected benefits outweigh risks

- UK National Institute for Health & Care Excellence. Guideline for LBP and sciatica 2016

Do not offer opioids for chronic low back pain

References

- ↑ 1.0 1.1 Krebs et al.. Effect of Opioid vs Nonopioid Medications on Pain-Related Function in Patients With Chronic Back Pain or Hip or Knee Osteoarthritis Pain: The SPACE Randomized Clinical Trial. JAMA 2018. 319:872-882. PMID: 29509867. DOI. Full Text.

- ↑ 2.0 2.1 McPherson et al.. Changes in pain intensity after discontinuation of long-term opioid therapy for chronic noncancer pain. Pain 2018. 159:2097-2104. PMID: 29905648. DOI. Full Text.

- ↑ Understanding the role of opioids in chronic non-malignant pain. https://bpac.org.nz/2018/opioids-chronic.aspx

Literature Review

- Reviews from the last 7 years: review articles, free review articles, systematic reviews, meta-analyses, NCBI Bookshelf

- Articles from all years: PubMed search, Google Scholar search.

- TRIP Database: clinical publications about evidence-based medicine.

- Other Wikis: Radiopaedia, Wikipedia Search, Wikipedia I Feel Lucky, Orthobullets,