Scheuermann's Disease

Scheuermann's disease (SD) is a developmental disorder in adolescence that causes a rigid or relatively rigid hyperkyphosis of the thoracic or thoracolumbar spine and has specific radiographic findings. It most commonly occurs in the adolescent growth spurt between the ages of 12 and 15, but can occur as early as late preschool.[1]

Classification

There are two curve patterns. [1]

- Type I: Thoracic pattern. the most common. Associated with a non-structural hyperlordosis of the lumbar and cervical spine.

- Type II: Thoracolumbar pattern. this is rare, and is more likely to progress during adult life. Also known as lumbar type 2 Scheuermann's disease, or Apprentice kyphosis. This is more common in athletic adolescent males or in those that do heavy lifting. There is no significant kyphosis clinically.

Aetiology

The aetiology is not completely understood. It starts prior to puberty after ossification of the vertebral ring apophysis and is most prominent during the adolescent growth spurt. There appears to be disconcordant vertebral endplate mineralisation and ossification which leads to disproportional vertebral body growth and wedge formation.

Theories include:

- Genetic: It seems to have an autosomal dominant inheritance pattern with high penetrance and variable expressivity. A large twin study that looked at self-reported previous diagnoses of SD found that there was a major genetic contribution with odds ratios of 32.92 in monozygotic and 6.25 in dizygotic twins, and heritability of 74%. [2]

- Mechanical factors: Repetitive activities including repetitive loading in the immature spine. It is thought that there may be an altered remodelling response to abnormal biomechanical stress. Individuals with SD tend to be heavier and taller but this may be a consequence of other upstream factors (e.g. hormonal), rather than a cause of SD itself.

- Increased growth hormone levels

- Defective collagen fibril formation with increased proteoglycan levels and resultant weakened vertebral end plate

- Irregular mineralisation and altered endochondral ossification.

- Juvenile osteoporosis: many studies have found lower bone mineral density in SD patients. However it isn't known if this is a consequence of decreased physical activity due to pain, or a primary causative factor of SD.

- Sternum length: There is an association of shorter sternums with SD development. It isn't known if this is a primary cause, but if it is it could be explained by the shorter sternum causing increased forces on the anterior aspect of the thoracic vertebrae.

- Trauma

- Vitamin A deficiency

- Poliomyelitis

- Epiphysitis

Epidemiology

Prevalence studies report a range of 0.4 to 8%. These figures may be a lower limit due to the condition being generally underdiagnosed. Most studies indicate a slight male predominance. It typically presents between the ages of 12 and 15.[1]

Clinical Features

History

The most common reason for individuals with SD seeking healthcare is cosmetic concern related to deformity.

Patients may have pain, but this is usually mild, and tends to improve when growth is completed. The pain is generally located at the apex of the curve and may be worse with activity. Spondylolisthesis is more common in SD and patients with this may have low back pain.

Examination

Spinal range of motion should be assessed in all planes: flexion/extension, lateral bending, and rotation. The kyphosis is present in the thoracic or thoracolumbar region and is fixed, i.e. it is still present with hyperextension of the spine. The Adam's test involves having the patient bend forward, and is positive if there is a sharply angulated deformity (a gibbus).[1]

There is a varying degree of compensatory lumbar hyperlordosis with a negative sagittal balance and forward head posture. These lumbar and cervical curves are flexible. Scoliosis is present in approximately a third of patients and tends to be minor.

There may be hyperpigmentation at the apex of the kyphosis. This is thought to be due to skin friction from sitting on chairs. There is often shortening of the anterior shoulder girdle, hamstring, and iliopsoas muscles. There may be localised tenderness at the apex of the curve.

Neurological abnormalities are rare. Deficits may occur in the presence of thoracic disc herniation, kyphotic angulation, spinal cord tenting, extradural spinal cysts, osteoporotic compression fractures, and anterior spinal artery injury.

Restrictive lung disease may occur with severe angulation of over 100° with the apex of the curve in the 1st to 8th vertebrae.

Imaging

The standing lateral radiograph is used to make the diagnosis. The arms elevated or held on the ipsilateral clavicles. The pelvis and hips are included for calculation of spinopelvic measurements. Most studies use the 1964 Sorenson criteria:

- Thoracic Cobb angle of at least 40° or thoracolumbar kyphosis of >30°

- Anterior vertebral wedging in three or more adjacent vertebra, greater or equal to 5°

The 1987 Drummond criteria only required two or more adjacent vertebrae. The 1987 Sachs criteria only require one vertebra to be wedged along with a thoracic kyphosis of more than 45° (T3-T12).[1]

Cobb Angle Measurement on Lateral Imaging[3]

- Line is drawn along the superior endplate of the most tilted vertebrae on the cephalad portion of the kyphotic curve

- Line is drawn along the inferior endplate of the most tilted vertebrae on the caudal portion of the kyphotic curve

- The angle formed by the intersection of lines perpendicular to the above-described lines is the measured Cobb angle

- Hyperkyphosis is described as, measured Cobb angle greater than 40 degrees

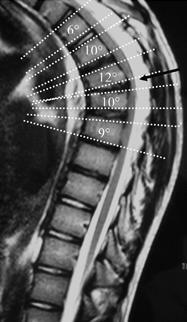

Anterior Wedging Measurement on Lateral Imaging[3]

- Line is drawn from posterior to anterior along the superior endplate

- Line is drawn from posterior to anterior along the inferior endplate

- The angle formed by the intersection of these lines anteriorly is the measured Wedge angle

- Anterior wedging of greater than or equal to 5 degrees in three or more adjacent vertebral bodies, with an associated rigid hyperkyphosis greater than 40 degrees, is diagnostic for Scheuermann disease

Normal Values

- Thoracic kyphosis: 25° to 45°. It tends to increase with age in the normal population and is slightly greater in women.

- Lumbar lordosis: 36° to 56°.

- Transitional T10-L2 zone: slightly lordotic at 0° to 10°.

Other signs of SD include vertebral endplate irregularities due to extensive disc invagination, and intervertebral disc space narrowing most pronounced anteriorly. SD is associated with Schmorl's nodes, limbus vertebrae, scoliosis, and spondylolisthesis.

The sagittal balance of the spine can be assessed by looking at the C7 plumb line. This is the C7 vertebral body vertical axis and it should lie vertically within 2cm of the sacral promontory. In patients with SD the spine tends to have a negative balance with the C7 plumb line lying behind the sacral promontory.[1]

The rigidity of the kyphosis can be assessed by imaging the patient while they lie in hyperextension over a bolster.[4]

MRI is performed in some cases to assess for disc and spinal cord abnormalities.

Differential Diagnosis

The main differential is postural kyphosis. These conditions can be differentiated by the forward bending test. In postural kyphosis there is a smooth, flexible, and symmetric contour. In SD, there is an area of angulation in a fixed kyphotic curve.[1]The postural kyphotic curve is correctable in hyperextension and in supine.[4]

- Scheuermann's disease

- Postural kyphosis

- Idiopathic kyphosis

- Ankylosing spondylitis

- Osteochondral dystrophies

- Spondyloepiphyseal dysplasias

- Congenital kyphosis

Treatment

The rarer lumbar Scheuermann's disease is non-progressive and typically resolves with rest, activity modification, and time. [1]

Prognosis

The long-term prognosis is largely unknown, as is the likelihood of progression at a certain degree of severity. In the long-term, individuals with SD have more pain than controls. There doesn't appear to be a correlation between quality of life, health, or back pain with the severity of disease. However patients may have an increased risk of disability, lower quality of life, and poorer general health.

Summary

- Thoracic kyphosis is measured from the most proximal to most distal vertebra included in the curve using the Cobb method.

References

- ↑ 1.0 1.1 1.2 1.3 1.4 1.5 1.6 1.7 Russell & Phillips. A preliminary comparison of front and back squat exercises. Research quarterly for exercise and sport 1989. 60:201-8. PMID: 2489844. DOI.

- ↑ Damborg et al.. Prevalence, concordance, and heritability of Scheuermann kyphosis based on a study of twins. The Journal of bone and joint surgery. American volume 2006. 88:2133-6. PMID: 17015588. DOI.

- ↑ 3.0 3.1 Mansfield JT, Bennett M. Scheuermann Disease. [Updated 2020 Aug 15]. In: StatPearls [Internet]. Treasure Island (FL): StatPearls Publishing; 2021 Jan-. Available from: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK499966/

- ↑ 4.0 4.1 Tsirikos & Jain. Scheuermann's kyphosis; current controversies. The Journal of bone and joint surgery. British volume 2011. 93:857-64. PMID: 21705553. DOI.

Literature Review

- Reviews from the last 7 years: review articles, free review articles, systematic reviews, meta-analyses, NCBI Bookshelf

- Articles from all years: PubMed search, Google Scholar search.

- TRIP Database: clinical publications about evidence-based medicine.

- Other Wikis: Radiopaedia, Wikipedia Search, Wikipedia I Feel Lucky, Orthobullets,