◒

ACL Injury: Difference between revisions

From WikiMSK

No edit summary |

m (Text replacement - "Knee & Leg" to "Knee and Leg") |

||

| Line 85: | Line 85: | ||

{{Reliable sources|synonym1=Anterior+Cruciate+Ligament+Injury|synonym2=Anterior+Cruciate+Ligament+Tear}} | {{Reliable sources|synonym1=Anterior+Cruciate+Ligament+Injury|synonym2=Anterior+Cruciate+Ligament+Tear}} | ||

[[Category:Knee | [[Category:Knee and Leg]] | ||

[[Category:Partially complete articles]] | [[Category:Partially complete articles]] | ||

Revision as of 15:11, 8 May 2021

This article is still missing information.

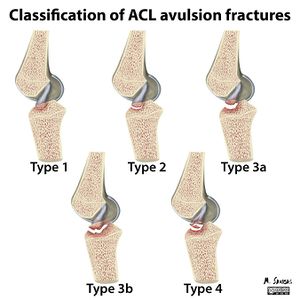

Classification

The most commonly used classification is from Zarincznyj in 1997, which was modified from Meyers and McKeevers in 1959. Under this system, injuries are classified into four types.

ACL Surgery

Once torn, it doesn’t heal. Reconstruction does not make it normal – posttraumatic osteoarthritis can occur regardless of management

Surgical vs non-surgical management

- RCT of 121 “young active adults”

- Rehab (plus delayed surgery if needed) vs rehab plus early surgery

- 5 year follow up: no differences in ability to return to sport, knee function, or rate of meniscal injury

- 50% crossover (50% in rehab group crossed over to surgery)

- Take-away: 50% can be managed non-operatively

- In my opinion we don’t know if those other 50% eventually managed operatively would have better outcomes than sham surgery

Subsequent OA and Meniscal Tears

- Metanalysis 2019, comparing surgery vs non-surgical treatment with 10 year follow up

- Patient reported outcomes the same

- Higher rate of radiographic knee OA

- Lower rate of secondary meniscal injury and meniscal surgery

- Reduced laxity

- Significant methodological flaws in the included studies and heterogeneity

Copers vs non-copers

- Copers – use neuro-musculo-skeletal strategies to dynamically stabilise their ACL-deficient knee even with pivoting

- Non-copers – knee instability, higher rates of surgery

- Not possible to classify this early on

- in one study 70% of those initially classified as non-copers, were copers after 1 year of non-operative management. And only 60% of potential copers were true copers.

ACL Reconstruction

- Indications??

- Recurrent instability

- Associated tear when amenable to repair

- Associated ligament injury especially posterolateral corner

- Professional and elite players

- High-risk occupation (where instability could cause harm)

- ?Adolescents, risk of instability, ?protect against future meniscal and chondral damage.

- Delay surgery until normal range of motion, effusion largely resolved and able to walk comfortably (to reduce risk of athrofibrosis i.e. stiffness)

ACL Graft Selection

- Bone-Patella-Bone

- possible earlier graft fixation and stability due to included portion of bone

- anterior knee pain up to 1 year

- possible higher rate of OA.

- Hamstring

- Initial fixation may be slower and weaker (no bone), but quadruple strand is stronger than B-P-B

- Donor site pain resolves by 3 months

- hamstring strength normal by 12 months.

- Other: Allografts, quadriceps graft,

ACL Postoperative

[4] Graft re-rupture (from surgical failure or re-trauma) Outcomes worse for revision ACL repair Increased risk tear contralateral knee – 7% cumulative incidence 5770 reconstructed knees – 60% returned to pre-injury level, and 44% returned to competitive sport. Professional players – 90% return to play by 12 months, sensible?? Shorter careers.

Unknown Unknowns

- Cultural norms in professional sport and other areas

- ?Uncertainty of non-operative treatment

- Loss of option of early ACL repair

- ACL-deficient sport ?future meniscal and cartilage injury

- What is success, return to pivoting sport? What is in the athlete’s best interest?

- “Doing nothing” is hard

Rehabilitation for Athletes

- Protection and controlled mobilisation

- Controlled training

- More intensive training

- Return to play (many months)

References

- ↑ Frobel R et al, Treatment for acute anterior cruciate ligament tear: five year outcome of randomised trial BMJ 2013;346:f232

- ↑ Lien-Iversen, T., Morgan, D. B., Jensen, C., Risberg, M. A., Engebretsen, L., & Viberg, B. (2019). Does surgery reduce knee osteoarthritis, meniscal injury and subsequent complications compared with non-surgery after ACL rupture with at least 10 years follow-up? A systematic review and meta-analysis. British Journal of Sports Medicine, bjsports–2019–100765.

- ↑ Moksnes, H., Snyder-Mackler, L., & Risberg, M. A. (2008). Individuals With an Anterior Cruciate Ligament-Deficient Knee Classified as Noncopers May Be Candidates for Nonsurgical Rehabilitation. Journal of Orthopaedic & Sports Physical Therapy, 38(10), 586–595. doi:10.2519/jospt.2008.2750

- ↑ Ardern CL, Webster KE, Taylor NF, Feller JA. Return to sport following anterior cruciate ligament reconstruction surgery: a systematic review and meta-analysis of the state of play. Br J Sports Med 2011;45:596-606.

- ↑ Weiler, R. (2015). Unknown unknowns and lessons from non-operative rehabilitation and return to play of a complete anterior cruciate ligament injury in English Premier League football. British Journal of Sports Medicine, 50(5), 261–262. doi:10.1136/bjsports-2015-095141

- ↑ Bizzini, M., Hancock, D., & Impellizzeri, F. (2012). Suggestions From the Field for Return to Sports Participation Following Anterior Cruciate Ligament Reconstruction: Soccer. Journal of Orthopaedic & Sports Physical Therapy, 42(4), 304–312. doi:10.2519/jospt.2012.4005

Literature Review

- Reviews from the last 7 years: review articles, free review articles, systematic reviews, meta-analyses, NCBI Bookshelf

- Articles from all years: PubMed search, Google Scholar search.

- TRIP Database: clinical publications about evidence-based medicine.

- Other Wikis: Radiopaedia, Wikipedia Search, Wikipedia I Feel Lucky, Orthobullets,