Cervical Radicular Pain and Radiculopathy

Definitions

- Main article: Cervical Spine Pain Definitions

Cervical radiculopathy is characterised by objective loss of neurologic function. Loss of function is some combination of sensory loss, motor loss, or impaired reflexes, in a segmental distribution. Pain is not a component of radiculopathy, and so is distinguished from cervical radicular pain.[1]

Pathophysiology

Not much is known about the causes and mechanisms of cervical radicular pain. The literature often uses the term cervical radiculopathy, but radiculopathy and radicular pain are not synonymous.

Radiculopathy arises from either direct compression of a cervical spinal nerve or root, or by ischaemia from vascular injury to their blood supply. There is a conduction block along the affected axons which results in sensory or motor loss. Compression of axons, including those of the lumbar nerve roots, does not cause activity in nociceptive afferent fibres. Meanwhile, compression of a dorsal root ganglion does cause pain through activation of Aβ and C fibres. The causes of cervical radicular pain cannot therefore be attributed to the same causes as those of radiculopathy.

It is thought that inflammation of the cervical nerve roots is the underlying mechanism through which radicular pain occurs secondary to disc herniation. There are pro-inflammatory molecules in disc material. Meanwhile, inflammation is not the cause of pain in other causes of radicular pain when due to tumours, cysts, and osteophytes. In these conditions it must be through dorsal root ganglion compression that pain occurs, as these conditions are non-inflammatory in nature.[1]

Aetiology

- Disc

- Protrusion

- Osteophytes

- Facet joint

- Osteophytes

- Ganglion

- Tumor

- Rheumatoid arthritis

- Gout

- Ankylosing spondylitis

- Fracture

- Vertebral body

- Tumor

- Paget’s disease

- Fracture

- Osteomyelitis

- Hydatid

- Hyperparathyroidism

- Meninges

- Cysts

- Meningioma

- Dermoid cyst

- Epidermoid cyst

- Epidural abscess

- Epidural hematoma

- Blood vessels

- Angioma

- Arteritis

- Nerve sheath

- Neurofibroma

- Schwannoma

- Nerve

- Neuroblastoma

- Ganglioneuroma

The most common cause of cervical radiculopathy is intervertebral disc herniation. It is not completely clear why some people with disc herniation develop radiculopathy while others don't but it appears that an inflammatory response can lead to neurophysiologic dysfunction.

The second most common cause is degenerative change. This includes ligamentous hypertrophy, hyperostosis, disc degeneration, facet joint hypertrophy, and uncovertebral joint hypertrophy. Hypertrophy of the latter two structures can lead to foraminal stenosis and nerve root compression. Osteophytosis can also be involved in compression.

Other causes are less common such as facet joint cysts, trauma, haematomas, fibroproliferation, and various tumours.[2]

Clinical Features

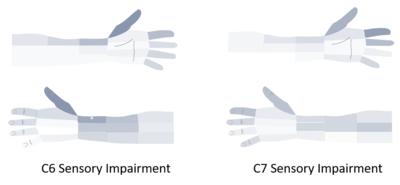

Cervical radiculopathy is characterised by negative objective signs: sensory loss, motor loss, or impaired reflexes, in a segmental distribution. The sensory loss occurs in the upper limbs, and tends to be dermatomal in distribution.[1] Notably however C6 and C7 cannot be differentiated based on dermatomes alone.[3]

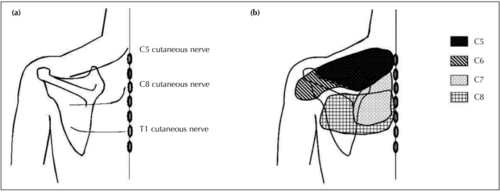

The pattern of cervical radicular pain on the other hand is not dermatomal. The pain can be felt proximally in the scapula and shoulder girdle, and scapula pain usually precedes pain in the arm and/or fingers. This is analogous to the common finding of buttock pain with lumbar radicular syndrome. The reason it is not dermatomal is likely due to the pain not being restricted to cutaneous fibres, but there is also a deeper pain arising from the muscles and joints. The segmental innervation of the skin (dermatomes) is different to that of the deeper tissues. The muscles of the shoulder girdle are supplied by C6 and C7, very different to their dermatomes. And so the segmental innervation of muscles is more closely related to the radicular pain patterns than dermatomes, while dermatomes are more helpful for patterns of sensory loss in radiculopathy.[1][4]

(b) The site of radicular pain involving the C6 root overlaps with that of the C5 root, and also involves the posterior deltoid.[4]

The site of scapula pain may be a helpful data point in determining the affected level in cervical radicular pain. Mizutamari et al suspect that scapula pain occurs through the medial branches of the dorsal rami of the cervical nerves. They found that there was no cutaneous course of C6 and C7 and that these patients complained of deep scapula pain only. This is compared to patients with C5 and C8 lesions having both superficial and deep pain.[4]

| Nerve root | Shoulder Girdle Region | Deep or superficial |

|---|---|---|

| C5 | Suprascapular region | Superficial and deep pain |

| C6 | Suprascapular to posterior deltoid region | Deep pain |

| C7 | Interscapular region | Deep pain |

| C8 | Interscapular and scapular regions | Superficial and deep pain |

Prognosis

The prognosis is generally good, although not as good as neck pain alone. One study found that recurrences were common at 31.7%, and 90.5% had minimal or no pain at a mean follow up of 5.9 years. A systematic review found that most patients improve within six months. Complete improvement took two to three years and was achieved by 83% of people. This recovery has radiographic correlation as half of cervical disc herniations decrease within the first six months, and 75% decrease by more than 50% within two years. Risk factors for poor outcome is an ongoing worker's compensation claim.[5]

Treatment

Conservative

Conservative therapy includes measures such as oral medication, physiotherapy, traction, collar, bed rest, exercise, and TENS. Much of the comparative research on conservative therapy is quite old (?external validity), all of it showing no benefit for any particular conservative passive intervention, and that conservative therapy is effectively equal to sham therapy. A 1966 study found no difference between traction, sham traction, collar, heat, and placebo tablets.[6] A 1970 study found no difference between exercise, traction, and no treatment. A 1990 study found no clinically important difference between traction and placebo traction.[7]

Injections

This refers to transforaminal or interlaminar epidural corticosteroid injections. The standard preferred technique now is transforaminal. This has been evaluated in multiple different trials. The Pain Physician Epidural Guidelines found that there is level I evidence for cervical interlaminar epidural injections with strong recommendation for long-term effectiveness.[8]

References

- ↑ 1.0 1.1 1.2 1.3 1.4 Bogduk. The anatomy and pathophysiology of neck pain. Physical medicine and rehabilitation clinics of North America 2011. 22:367-82, vii. PMID: 21824580. DOI.

- ↑ Manchikanti L, et al. Epidural Interventions in the Management of Chronic Spinal Pain: American Society of Interventional Pain Physicians (ASIPP) Comprehensive Evidence-Based Guidelines. Pain Physician. 2021 Jan;24(S1):S27-S208. PMID: 33492918.

- ↑ 3.0 3.1 Rainville et al.. Exploration of sensory impairments associated with C6 and C7 radiculopathies. The spine journal : official journal of the North American Spine Society 2016. 16:49-54. PMID: 26253986. DOI.

- ↑ 4.0 4.1 4.2 Mizutamari et al.. Corresponding scapular pain with the nerve root involved in cervical radiculopathy. Journal of orthopaedic surgery (Hong Kong) 2010. 18:356-60. PMID: 21187551. DOI.

- ↑ Cohen & Hooten. Advances in the diagnosis and management of neck pain. BMJ (Clinical research ed.) 2017. 358:j3221. PMID: 28807894. DOI.

- ↑ Pain in the neck and arm: a multicentre trial of the effects of physiotherapy, arranged by the British Association of Physical Medicine. Br Med J. 1966 Jan 29;1(5482):253-8. doi: 10.1136/bmj.1.5482.253. PMID: 5322503; PMCID: PMC1843524.

- ↑ Goldie I, Landquist A. Evaluation of the effects of different forms of physiotherapy in cervical pain. Scand J Rehabil Med. 1970;2(2):117-21. PMID: 5523822.

- ↑ Manchikanti L, et al. Epidural Interventions in the Management of Chronic Spinal Pain: American Society of Interventional Pain Physicians (ASIPP) Comprehensive Evidence-Based Guidelines. Pain Physician. 2021 Jan;24(S1):S27-S208. PMID: 33492918.

Literature Review

- Reviews from the last 7 years: review articles, free review articles, systematic reviews, meta-analyses, NCBI Bookshelf

- Articles from all years: PubMed search, Google Scholar search.

- TRIP Database: clinical publications about evidence-based medicine.

- Other Wikis: Radiopaedia, Wikipedia Search, Wikipedia I Feel Lucky, Orthobullets,