Lateral Elbow Tendinopathy: Difference between revisions

m (→Imaging) |

|||

| (79 intermediate revisions by the same user not shown) | |||

| Line 1: | Line 1: | ||

{{partial}} | |||

{{condition | |||

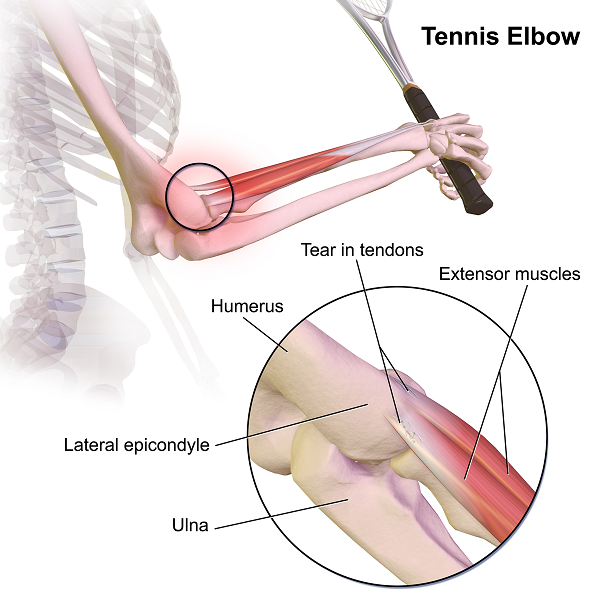

|image=Lateral Elbow Tendinopathy.png | |||

|name=Lateral Elbow Tendinopathy | |||

|synonym=Lateral Epicondylitis / Epicondylosis / Epicondylalgia, Tennis Elbow | |||

|definition=Pain at the tendon insertion or myotendinous junction during loading of the wrist extensor muscles | |||

|epidemiology= | |||

|causes= | |||

|pathophysiology= | |||

|classification= | |||

|primaryprevention= | |||

|secondaryprevention= | |||

|riskfactors= | |||

|history= | |||

|examination= | |||

|diagnosis=All three of epicondylar pain, epicondylar tenderness (assessment with elbow flexed at 90 degrees), pain on resisted extension of the wrist | |||

|tests= | |||

|ddx= | |||

|treatment=Activity modification, progressive load program, injections | |||

|prognosis= | |||

}} | |||

==Definition== | ==Definition== | ||

There is no | There is no formal definition. It is generally described as pain at the tendon insertion or myotendinous junction during loading of the wrist extensor muscles. Lateral elbow tendinopathy is also commonly called tennis elbow, lateral epicondylitis, lateral epicondylalgia, and elbow tendinosis/tendinitis. | ||

==Epidemiology== | ==Epidemiology== | ||

Lateral elbow tendinopathy is the most common cause of lateral elbow pain. | |||

The | The prevalence was 1.3% in an observational study of 5871 working-age Finns <ref name="finns">Shiri R, Viikari-Juntura E, Varonen H, Heliövaara M. Prevalence and determinants of lateral and medial epicondylitis: a population study. Am J Epidemiol. 2006;164(11):1065-1074. doi:10.1093/aje/kwj325</ref>. The peak prevalence in females is in the 5th decade. The annual incidence is 4.23 per 1000 <ref>Walker-Bone K et al. Prevalence and impact of musculoskeletal disorders of the upper limb in the general population. Arthritis Rheum. 2004;51:642-651.</ref>. | ||

==Risk Factors== | |||

Common risk factors are summarised below <ref name="finns"></ref> | |||

*Smoking | |||

*Obesity | |||

*Age 45-54 | |||

* Repetitive movements especially wrist extension and supination for at least two hours daily | |||

*Forceful activity (lifting loads over 20kg) | |||

* New or sudden overuse of tendon (e.g. lifting a new baby, new exercise routine, new gardening, handling heavy tools or heavy load) | |||

* Low job control | |||

* Low social support | |||

The highest load at the ECRB tendon is when the elbow is extended and the forearm pronated. | |||

Doesn't increase risk: keyboard use, working with arms above shoulder-height, exposure to hand-transmitted vibrations | |||

Note: Tennis is associated with the condition in less than 10 in 100 patients, and is more common in recreational players. See Hatch et al for discussion about racket grip sizes. <ref>Hatch GF 3rd, Pink MM, Mohr KJ, Sethi PM, Jobe FW. The effect of tennis racket grip size on forearm muscle firing patterns. Am J Sports Med. 2006;34(12):1977-1983. doi:10.1177/0363546506290185</ref> | |||

===Poor Prognostic Factors=== | |||

Poor prognostic factors<ref>Smidt N, Lewis M, VAN DER Windt DA, Hay EM, Bouter LM, Croft P. Lateral epicondylitis in general practice: course and prognostic indicators of outcome. J Rheumatol. 2006;33(10):2053-2059.</ref> | |||

* | *High work physical strain, such as handling tools, handling heavy loads, repetitive movements, and low job control<ref>Haahr JP et al. Prognostic factors in lateral epicondylitis: a randomized trial with one-year follow-up in 266 new cases treated with minimal occupational intervention or the usual approach in general practice. Rheumatology (Oxford). 2003;42:1216-1225</ref> | ||

*Dominant side | |||

** | *Shoulder or neck pain<ref>Smidt N et al. Lateral epicondylitis in general practice: course and prognostic indicators of outcome. J Rheumatol. 2006;33:2053-2059</ref>. Neck pain is more common in those with lateral elbow tendinopathy<ref>Berglund KM et al. Prevalence of pain and dysfunction in the cervical and thoracic spine in persons with and without lateral elbow pain. Man Ther. 2008;13:295-299</ref> | ||

* | *Symptoms greater than 3 months | ||

* | *Severe Pain <ref>Smidt N et al. Lateral epicondylitis in general practice: course and prognostic indicators of outcome. J Rheumatol. 2006;33:2053-2059</ref> | ||

A longitudinal study of patients with lateral elbow tendinopathy did not find any association between psychological factors and prognosis <ref>Coombes BK et al. Cold hyperalgesia associated with poorer prognosis in lateral epicondylalgia: a 1-year prognostic study of physical and psychological factors. Clin J Pain. 2015;31:30-35.</ref> | |||

===Central Sensitisation=== | |||

In individuals with lateral elbow tendinopathy there is evidence of heightened nociceptive withdrawal reflexes and widespread mechanical hyperalgesia<ref>Fernández-Carnero J et al. Widespread mechanical pain hypersensitivity as sign of central sensitization in unilateral epicondylalgia: a blinded, controlled study. Clin J Pain. 2009;25:555-561.</ref> A subgroup of patients reporting severe levels of pain and disability display cold hyperalgesia (mean, 13.7°C) <ref>Coombes BK et al. Thermal hyperalgesia distinguishes those with severe pain and disability in unilateral lateral epicondylalgia. Clin J Pain. 2012;28:595-601.</ref> Cold pain threshold is an independent predictor of short- and long-term prognosis in untreated individuals with lateral elbow tendinopathy. <ref>Coombes BK, Bisset L, Vicenzino B. Cold hyperalgesia associated with poorer prognosis in lateral epicondylalgia: a 1-year prognostic study of physical and psychological factors. Clin J Pain. 2015;31:30-35.</ref> cold pain thresholds greater than 13°C have been linked to an increased risk of persistent pain | |||

==Natural History== | |||

It is often described as a self limiting condition. A “wait and see” approach can see improvement within one year <ref>Bisset L et al. Conservative treatments for tennis elbow—do subgroups of patients respond differently? Rheumatology (Oxford). 2007;46:1601-1605.</ref><ref> Smidt N et al. Lateral epicondylitis in general practice: course and prognostic indicators of outcome. J Rheumatol. 2006;33:2053-2059.</ref>. A third of patients have prolonged discomfort lasting in excess of 1 year despite interventions. 5% of patients do not respond to conservative physical interventions and undergo surgery. | |||

==Pathogenesis== | |||

It is generally stated that the extensor carpi radialis brevis tendon is the structure most commonly implicated. The extensor digitorum or extensor carpi ulnaris may be the culprit if middle finger extension is more painful than wrist extension <ref>Fairbank SM, Corlett RJ. The role of the extensor digitorum communis muscle in lateral epicondylitis. J Hand Surg Br. 2002;27(5):405-409. doi:10.1054/jhsb.2002.0761</ref> | |||

Factors thought to be relevant: | |||

* Repeated microtearing and healing attempts | |||

* Non inflammatory "angiofibroblastic hyperplasia" also known as "neovessels" or simply "angiogenesis" | |||

* Formation of nonfunctional blood vessels | |||

* Collagen scaffold disrupted by fibroblasts and vascular granulation | |||

* Abnormal tissue has a large number of nociceptive nerve fibres. | |||

* Tearing may be primary with degenerative change being secondary or vice versa. | |||

Central neural mechanisms may be at play. Those with affected tendons tend to grip in a flexed wrist position, even with their unaffected side. There is also a bilateral reduction in speed and reaction time. <ref>Bisset LM, Russell T, Bradley S, Ha B, Vicenzino BT. Bilateral sensorimotor abnormalities in unilateral lateral epicondylalgia. Arch Phys Med Rehabil. 2006;87(4):490-495. doi:10.1016/j.apmr.2005.11.029</ref> | |||

Pathology Studies | Pathology Studies | ||

* | Pathology studies have generally been histological in those undergoing surgery and imaging based. | ||

* | *Chard et al harvested 20 common extensor tendons in patients having a release procedure, and compared them to nine control biopsies, and performed an unblinded assessment. Common changes were glycosaminoglycan infiltration, new bone formation, fibrofatty change, partial rupture, and fibrocartilage formation. Inflammatory changes were only found in one sample <ref>Chard MD, Cawston TE, Riley GP, Gresham GA, Hazleman BL. Rotator cuff degeneration and lateral epicondylitis: a comparative histological study. Ann Rheum Dis 1994; 53:30-34</ref> | ||

* | * Regan et al undertook a similar smaller study with a blinded assessment. They corroborated the lack of inflammation, but did see hyaline degradation in all samples. They also noted vascular proliferation, fibroblastic proliferation, and calcific debris in some speciments.<ref>Regan W, Wold LE, Coonrad RW, Morrey BF. Microscopic histopathology of chronic refractory lateral epicondylitis. Am J Sports Med 1992; 20:746-749.</ref> | ||

* Maufulli et al did an non-controlled ultrasound studyOne study looked at using high definition ultrasound studies in patients with the syndrome of lateral epicondylitis<ref>Maffulli N, Regine R, Carrillo F, Capasso G, Minelli S. Tennis elbow: an ultrasonographic study in tennis players. Br J Sports Med 1990; 24:151-155.</ref> | |||

* Zeisig et al | * Zeisig et al usedh grey-scale ultrasonography and colour doppler in 17 patients in a total of 22 elbows, and compared them to 11 controls with 22 pain-free elbows. In 21/22 of the painful elbows, vascularity was shown. This was in contrast to only 2/22 of pain-free elbows. This was thought to correspond to vasculo-neural growth.<ref>Zeisig E, Ohberg L, Alfredson H. Extensor origin vascularity related to pain in patients with Tennis elbow. Knee Surg Sports Traumatol Arthrosc. 2006;14(7):659-663. doi:10.1007/s00167-006-0060-7</ref> | ||

* Tendonosis can be induced in the contralateral limb with unilateral overloading in one rabbit model of achilles tendinopathy<ref>Andersson G, Forsgren S, Scott A, et al. Tenocyte hypercellularity and vascular proliferation in a rabbit model of tendinopathy: contralateral effects suggest the involvement of central neuronal mechanisms. Br J Sports Med. 2011;45(5):399-406. doi:10.1136/bjsm.2009.068122</ref> | |||

==Imaging== | |||

Ultrasound and MRI have high sensitivity but limited specificity. Features seen on imaging include tendon thickening, focal areas of tendon hypo-echogenicity (US), decreased signal intensity (MRI). One meta-analysis of MRI studies found signal changes in 90% of affected and 50% of unaffected tendons <ref>Pasternack I et al. MR findings in humeral epicondylitis. A systematic review. Acta Radiol. 2001;42:434-440.</ref>. Diagnostic ultrasound by an examiner blinded to status found tendinopathic changes in 90% of patients and 53% of asymptomatic controls<ref>Heales LJ et al. Diagnostic ultrasound imaging for lateral epicondylalgia: a case–control study. Med Sci Sports Exerc. 2014;46:2070-2076.</ref>. | |||

It is important to note that most studies find a lack of association between the severity of tendon changes on imaging and symptoms in lateral elbow tendinopathy. However one study demonstrated that the presence of a lateral collateral tear and the size of any intrasubstance tendon tear detected by ultrasound is significantly associated with poorer prognosis in patients with lateral elbow pain<ref>Clarke AW et al. Lateral elbow tendinopathy: correlation of ultrasound findings with pain and functional disability. Am J Sports Med. 2010;38:1209-1214.</ref> | |||

== | ==Assessment== | ||

* Onset of pain is insidious | * Onset of pain is insidious | ||

* Can be diagnosed using the "Southampton examination schedule"<ref>Palmer K, Walker-Bone K, Linaker C, et al. The Southampton examination schedule for the diagnosis of musculoskeletal disorders of the upper limb. Ann Rheum Dis. 2000;59(1):5-11. doi:10.1136/ard.59.1.5</ref> | * Can be diagnosed using the "Southampton examination schedule"<ref>Palmer K, Walker-Bone K, Linaker C, et al. The Southampton examination schedule for the diagnosis of musculoskeletal disorders of the upper limb. Ann Rheum Dis. 2000;59(1):5-11. doi:10.1136/ard.59.1.5</ref> | ||

** All three of epicondylar pain, epicondylar tenderness, pain on resisted extension of the wrist | ** All three of epicondylar pain, epicondylar tenderness (assessment with elbow flexed at 90 degrees), pain on resisted extension of the wrist | ||

** Fairly accurate - sensitivity 73%, specificity 97%, kappa = 0.75 | ** Fairly accurate - sensitivity 73%, specificity 97%, kappa = 0.75 | ||

* Often also get pain with supination of the forearm, resisted third finger extension (with an extended elbow), pain on lifting a chair with a pronated hand. | * Often also get pain with supination of the forearm, resisted third finger extension (with an extended elbow), pain on lifting a chair with a pronated hand. | ||

| Line 63: | Line 98: | ||

* Imaging usually unnecessary, and extend of tendon damage is not correlated with the amount of pain. May be considered if no improvement. | * Imaging usually unnecessary, and extend of tendon damage is not correlated with the amount of pain. May be considered if no improvement. | ||

* | Reproduction of lateral elbow pain during manual palpation and/or active, passive, or combined movements of the cervical spine should raise suspicion of radicular or referred pain<ref>[Wainner RS et al. Reliability and diagnostic accuracy of the clinical examination and patient self-report measures for cervical radiculopathy. Spine (Phila Pa 1976). 2003;28:52-62.</ref> | ||

* | |||

* | *Neurological examination if indicated (radial nerve function, sensitisation) | ||

* | **Radial nerve neurodynamic testing: A positive test requires reproduction of the patient’s lateral elbow pain and alteration of symptoms by a sensitization manoeuver, such as cervical lateral flexion or scapular elevation | ||

* | **Clinical ice pain test: Pain intensity of more than 5/10, after 10 seconds of ice application indicates 90% likelihood of cold hyperalgesia | ||

==Differential Diagnoses== | |||

{{Lateral Elbow Pain DDX}} | |||

{{Generalised Elbow Pain DDX}} | |||

==Treatment== | ==Treatment== | ||

;Doing Nothing or Rest | |||

* Most patients recover at one year with or without treatment | * Most patients recover at one year with or without treatment | ||

*Avoidance of usual activities or counterforce bracing / Rationale: caused by excessive loads | |||

*Efficacy – no class I or 2 evidence | |||

*Class 3: two studies showing no benefit for rest | |||

*Class 4: most authorities recommend rest for first 2 weeks | |||

;Analgesia | |||

There is conflicting evidence for NSAIDs<ref>Pattanittum P et al. Non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs) for treating lateral elbow pain in adults. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2013;5</ref>. NSAIDs more appropriate for reactive than degenerative tendinopathy. | |||

;Nitric Oxide Patches | |||

Demonstrated benefit beyond placebo. Class 2 evidence: efficacy depends on appropriate physical stimulus / no effect if patches combined with stretching only. <ref>Paoloni JA et al. Randomised, double-blind, placebo-controlled clinical trial of a new topical glyceryl trinitrate patch for chronic lateral epicondylosis. Br J Sports Med. 2009;43:299-302.</ref> | |||

;Autologous Blood or PRP | |||

No evidence that this is at all effective beyond placebo. Conclusion from Krogh’s study - "Neither injection of PRP nor glucocorticoid was superior to saline with regard to pain reduction in lateral epicondylalgia at the primary end point at 3 months. However, injection of glucocorticoid had a short-term pain-reducing effect at 1 month in contrast to the other therapies. Injection of glucocorticoid in lateral epicondylalgia reduces both color Doppler activity and tendon thickness compared with PRP and saline." <ref>de Vos RJ et al. Autologous growth factor injections in chronic tendinopathy: a systematic review. Br Med Bull. 2010;95:63-77; Krogh TP et al. Treatment of lateral epicondylitis with platelet-rich plasma, glucocorticoid, or saline: a randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled trial. Am J Sports Med. 2013;41:625-635.</ref> | |||

;Exercises | |||

Effective exercise programmes incorporate progressive eccentric and isometric strengthening. Flexibility training may also be required. Eccentric exercise can be performed by holding a weight or a taut resistance band with the wrist extended. The wrist is then flexed against resistance. | Effective exercise programmes incorporate progressive eccentric and isometric strengthening. Flexibility training may also be required. Eccentric exercise can be performed by holding a weight or a taut resistance band with the wrist extended. The wrist is then flexed against resistance. | ||

| Line 87: | Line 136: | ||

*A similar smaller study found better outcomes in the eccentric strengthening group when using a rubber bar: [[:File:rubber bar lateral elbow.jpg]] .<ref>Tyler TF, Thomas GC, Nicholas SJ, McHugh MP. Addition of isolated wrist extensor eccentric exercise to standard treatment for chronic lateral epicondylosis: a prospective randomized trial. J Shoulder Elbow Surg. 2010;19(6):917-922. doi:10.1016/j.jse.2010.04.041</ref> | *A similar smaller study found better outcomes in the eccentric strengthening group when using a rubber bar: [[:File:rubber bar lateral elbow.jpg]] .<ref>Tyler TF, Thomas GC, Nicholas SJ, McHugh MP. Addition of isolated wrist extensor eccentric exercise to standard treatment for chronic lateral epicondylosis: a prospective randomized trial. J Shoulder Elbow Surg. 2010;19(6):917-922. doi:10.1016/j.jse.2010.04.041</ref> | ||

=== | See Day et al for an example of an open access comprehensive exercise program(level 5 evidence).<ref>{{#pmid:31598419}}</ref> | ||

More recently, the Tyler Twist Technique has shown promise, done with a yellow Therabar.<ref>{{Cite journal|last=Kazi|first=Fatimah|last2=Patil|first2=Deepali S|date=2023-10-10|title=Effects of the Tyler Twist Technique Versus Active Release Technique on Pain and Grip Strength in Patients With Lateral Epicondylitis|url=https://www.cureus.com/articles/153907-effects-of-the-tyler-twist-technique-versus-active-release-technique-on-pain-and-grip-strength-in-patients-with-lateral-epicondylitis|journal=Cureus|language=en|doi=10.7759/cureus.46799|issn=2168-8184|pmc=PMC10634653|pmid=37954758}}</ref> | |||

;Rest | |||

* Rest, avoid or alter activities responsible for symptoms | * Rest, avoid or alter activities responsible for symptoms | ||

;Activity Modification | |||

* For tennis players: lighter racket with smaller grip and less string tension, use 2 - handed backhand | * For tennis players: lighter racket with smaller grip and less string tension, use 2 - handed backhand | ||

;Orthotics | |||

* braces, forearm straps, wrist cock-up splints may reduce pain and improve function (level 2) | * braces, forearm straps, wrist cock-up splints may reduce pain and improve function (level 2) | ||

* Counter-force brace recommended as inexpensive and easy to use. Apply 6-10cm distal to elbow joint. | * Counter-force brace recommended as inexpensive and easy to use. Apply 6-10cm distal to elbow joint. | ||

;Medication | |||

* topical NSAIDs may help, inconsistent evidence for oral NSAIDs (level 2) | * topical NSAIDs may help, inconsistent evidence for oral NSAIDs (level 2) | ||

* topical GTN may help for patients having physical therapy (level 2) | * topical GTN may help for patients having physical therapy (level 2) | ||

;PRP and Autologous Blood | |||

A Cochrane review of 32 studies found that PRP and autologous blood were no better than placebo.<ref>Karjalainen TV, Silagy M, O'Bryan E, Johnston RV, Cyril S, Buchbinder R. Autologous blood and platelet-rich plasma injection therapy for lateral elbow pain. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2021 Sep 30;9(9):CD010951. doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD010951.pub2. PMID: 34590307; PMCID: PMC8481072.</ref> | |||

;Surgery | |||

Surgery generally involved excision of the degenerative tissue, and release of the tendon from the lateral epicondyle. There are no placebo controlled trials evaluating surgery for this condition. | |||

;Steroid injections | |||

Peritendinous steroid injections may provide short-term relief (up to 12 weeks), but result in increased pain and recurrence at one year (level 1)<ref>Coombes BK et al. Efficacy and safety of corticosteroid injections and other injections for management of tendinopathy: a systematic review of randomised controlled trials. Lancet. 2010;376:1751-1767.</ref> Side effects are common, with pain in 50% and skin atrophy in 20 – 30% | |||

{| class="wikitable" | {| class="wikitable" | ||

| Line 146: | Line 194: | ||

|54% | |54% | ||

|} | |} | ||

;Stretching | |||

Stretching is not recommended due to the compressive loads placed on the tendon. Stretching also causes disuse of the supinator and wrist extensor muscles. | |||

;Acupuncture | |||

==Article Downloads== | |||

[[File:Coombes2015 Management of Lateral Elbow Tendinopathy.pdf]] | |||

==See Also== | |||

<categorytree mode="pages">Elbow and Forearm</categorytree> | |||

==References== | ==References== | ||

<references/> | |||

{{Reliable sources|synonym1=Tennis+Elbow|synonym2=Lateral+Epicondylitis}} | |||

[[Category: | [[Category:Elbow and Forearm Conditions]] | ||

[[Category:Tendinopathies]] | [[Category:Tendinopathies]] | ||

Latest revision as of 10:19, 20 February 2024

Definition

There is no formal definition. It is generally described as pain at the tendon insertion or myotendinous junction during loading of the wrist extensor muscles. Lateral elbow tendinopathy is also commonly called tennis elbow, lateral epicondylitis, lateral epicondylalgia, and elbow tendinosis/tendinitis.

Epidemiology

Lateral elbow tendinopathy is the most common cause of lateral elbow pain.

The prevalence was 1.3% in an observational study of 5871 working-age Finns [1]. The peak prevalence in females is in the 5th decade. The annual incidence is 4.23 per 1000 [2].

Risk Factors

Common risk factors are summarised below [1]

- Smoking

- Obesity

- Age 45-54

- Repetitive movements especially wrist extension and supination for at least two hours daily

- Forceful activity (lifting loads over 20kg)

- New or sudden overuse of tendon (e.g. lifting a new baby, new exercise routine, new gardening, handling heavy tools or heavy load)

- Low job control

- Low social support

The highest load at the ECRB tendon is when the elbow is extended and the forearm pronated.

Doesn't increase risk: keyboard use, working with arms above shoulder-height, exposure to hand-transmitted vibrations

Note: Tennis is associated with the condition in less than 10 in 100 patients, and is more common in recreational players. See Hatch et al for discussion about racket grip sizes. [3]

Poor Prognostic Factors

Poor prognostic factors[4]

- High work physical strain, such as handling tools, handling heavy loads, repetitive movements, and low job control[5]

- Dominant side

- Shoulder or neck pain[6]. Neck pain is more common in those with lateral elbow tendinopathy[7]

- Symptoms greater than 3 months

- Severe Pain [8]

A longitudinal study of patients with lateral elbow tendinopathy did not find any association between psychological factors and prognosis [9]

Central Sensitisation

In individuals with lateral elbow tendinopathy there is evidence of heightened nociceptive withdrawal reflexes and widespread mechanical hyperalgesia[10] A subgroup of patients reporting severe levels of pain and disability display cold hyperalgesia (mean, 13.7°C) [11] Cold pain threshold is an independent predictor of short- and long-term prognosis in untreated individuals with lateral elbow tendinopathy. [12] cold pain thresholds greater than 13°C have been linked to an increased risk of persistent pain

Natural History

It is often described as a self limiting condition. A “wait and see” approach can see improvement within one year [13][14]. A third of patients have prolonged discomfort lasting in excess of 1 year despite interventions. 5% of patients do not respond to conservative physical interventions and undergo surgery.

Pathogenesis

It is generally stated that the extensor carpi radialis brevis tendon is the structure most commonly implicated. The extensor digitorum or extensor carpi ulnaris may be the culprit if middle finger extension is more painful than wrist extension [15]

Factors thought to be relevant:

- Repeated microtearing and healing attempts

- Non inflammatory "angiofibroblastic hyperplasia" also known as "neovessels" or simply "angiogenesis"

- Formation of nonfunctional blood vessels

- Collagen scaffold disrupted by fibroblasts and vascular granulation

- Abnormal tissue has a large number of nociceptive nerve fibres.

- Tearing may be primary with degenerative change being secondary or vice versa.

Central neural mechanisms may be at play. Those with affected tendons tend to grip in a flexed wrist position, even with their unaffected side. There is also a bilateral reduction in speed and reaction time. [16]

Pathology Studies Pathology studies have generally been histological in those undergoing surgery and imaging based.

- Chard et al harvested 20 common extensor tendons in patients having a release procedure, and compared them to nine control biopsies, and performed an unblinded assessment. Common changes were glycosaminoglycan infiltration, new bone formation, fibrofatty change, partial rupture, and fibrocartilage formation. Inflammatory changes were only found in one sample [17]

- Regan et al undertook a similar smaller study with a blinded assessment. They corroborated the lack of inflammation, but did see hyaline degradation in all samples. They also noted vascular proliferation, fibroblastic proliferation, and calcific debris in some speciments.[18]

- Maufulli et al did an non-controlled ultrasound studyOne study looked at using high definition ultrasound studies in patients with the syndrome of lateral epicondylitis[19]

- Zeisig et al usedh grey-scale ultrasonography and colour doppler in 17 patients in a total of 22 elbows, and compared them to 11 controls with 22 pain-free elbows. In 21/22 of the painful elbows, vascularity was shown. This was in contrast to only 2/22 of pain-free elbows. This was thought to correspond to vasculo-neural growth.[20]

- Tendonosis can be induced in the contralateral limb with unilateral overloading in one rabbit model of achilles tendinopathy[21]

Imaging

Ultrasound and MRI have high sensitivity but limited specificity. Features seen on imaging include tendon thickening, focal areas of tendon hypo-echogenicity (US), decreased signal intensity (MRI). One meta-analysis of MRI studies found signal changes in 90% of affected and 50% of unaffected tendons [22]. Diagnostic ultrasound by an examiner blinded to status found tendinopathic changes in 90% of patients and 53% of asymptomatic controls[23].

It is important to note that most studies find a lack of association between the severity of tendon changes on imaging and symptoms in lateral elbow tendinopathy. However one study demonstrated that the presence of a lateral collateral tear and the size of any intrasubstance tendon tear detected by ultrasound is significantly associated with poorer prognosis in patients with lateral elbow pain[24]

Assessment

- Onset of pain is insidious

- Can be diagnosed using the "Southampton examination schedule"[25]

- All three of epicondylar pain, epicondylar tenderness (assessment with elbow flexed at 90 degrees), pain on resisted extension of the wrist

- Fairly accurate - sensitivity 73%, specificity 97%, kappa = 0.75

- Often also get pain with supination of the forearm, resisted third finger extension (with an extended elbow), pain on lifting a chair with a pronated hand.

- Can get wrist extension weakness

- Range of motion usually normal

- Imaging usually unnecessary, and extend of tendon damage is not correlated with the amount of pain. May be considered if no improvement.

Reproduction of lateral elbow pain during manual palpation and/or active, passive, or combined movements of the cervical spine should raise suspicion of radicular or referred pain[26]

- Neurological examination if indicated (radial nerve function, sensitisation)

- Radial nerve neurodynamic testing: A positive test requires reproduction of the patient’s lateral elbow pain and alteration of symptoms by a sensitization manoeuver, such as cervical lateral flexion or scapular elevation

- Clinical ice pain test: Pain intensity of more than 5/10, after 10 seconds of ice application indicates 90% likelihood of cold hyperalgesia

Differential Diagnoses

- Lateral Elbow Tendinopathy

- Referred pain (Cervical spine, Upper thoracic spine, Myofascial)

- Synovitis of the radiohumeral joint

- Radiohumeral bursitis

- Radial Head Fractures

- Radial Head Dislocation

- Capitellar Osteochondritis Dissecans (Capitellum, Radius in adolescents)

- Capitellar Osteochondrosis

- Lateral Condyle Fracture

- Capitellum Fracture

- Lateral Collateral Ligament Complex Injury

- Radial Head Subluxation (Nursemaid Elbow)

- Radiocapitellar Osteoarthrosis

- Bone Neoplasm

- Soft Tissue Neoplasm

- Posterolateral Rotary Instability

- Posterior Interosseous Nerve Entrapment or Radial Neuropathy at the Spiral Groove

- Posterolateral Plica Syndrome

- Osteoarthritis

- If locking consider chondromalacia, osteochondritis, loose bodies

Treatment

- Doing Nothing or Rest

- Most patients recover at one year with or without treatment

- Avoidance of usual activities or counterforce bracing / Rationale: caused by excessive loads

- Efficacy – no class I or 2 evidence

- Class 3: two studies showing no benefit for rest

- Class 4: most authorities recommend rest for first 2 weeks

- Analgesia

There is conflicting evidence for NSAIDs[27]. NSAIDs more appropriate for reactive than degenerative tendinopathy.

- Nitric Oxide Patches

Demonstrated benefit beyond placebo. Class 2 evidence: efficacy depends on appropriate physical stimulus / no effect if patches combined with stretching only. [28]

- Autologous Blood or PRP

No evidence that this is at all effective beyond placebo. Conclusion from Krogh’s study - "Neither injection of PRP nor glucocorticoid was superior to saline with regard to pain reduction in lateral epicondylalgia at the primary end point at 3 months. However, injection of glucocorticoid had a short-term pain-reducing effect at 1 month in contrast to the other therapies. Injection of glucocorticoid in lateral epicondylalgia reduces both color Doppler activity and tendon thickness compared with PRP and saline." [29]

- Exercises

Effective exercise programmes incorporate progressive eccentric and isometric strengthening. Flexibility training may also be required. Eccentric exercise can be performed by holding a weight or a taut resistance band with the wrist extended. The wrist is then flexed against resistance.

There are inconsistencies in the methodological quality of research into eccentric strengthening for this condition. High quality research in other tendinopathies, in particular achilles tendinopathy, has shown benefit for including eccentric strengthening in a rehabilitation programme. One systematic review in 2003 showed mixed results. [30]. A more recent review in 2014 found three high quality studies, seven medium quality studies, and two low quality studies. They concluded that the evidence supports the inclusion of eccentric strengthening as part of a multimodal approach to rehabilitation[31]

Some of the better quality studies:

- Standard physical therapy versus standard therapy plus eccentric stregnthening. Patients in the eccentric strengthening group had marked reductions in pain, disability, and improvement in tendon appearance on ultrasound at one month. At completion the eccentric training group had no strength deficit. [32]

- A similar smaller study found better outcomes in the eccentric strengthening group when using a rubber bar: File:rubber bar lateral elbow.jpg .[33]

See Day et al for an example of an open access comprehensive exercise program(level 5 evidence).[34]

More recently, the Tyler Twist Technique has shown promise, done with a yellow Therabar.[35]

- Rest

- Rest, avoid or alter activities responsible for symptoms

- Activity Modification

- For tennis players: lighter racket with smaller grip and less string tension, use 2 - handed backhand

- Orthotics

- braces, forearm straps, wrist cock-up splints may reduce pain and improve function (level 2)

- Counter-force brace recommended as inexpensive and easy to use. Apply 6-10cm distal to elbow joint.

- Medication

- topical NSAIDs may help, inconsistent evidence for oral NSAIDs (level 2)

- topical GTN may help for patients having physical therapy (level 2)

- PRP and Autologous Blood

A Cochrane review of 32 studies found that PRP and autologous blood were no better than placebo.[36]

- Surgery

Surgery generally involved excision of the degenerative tissue, and release of the tendon from the lateral epicondyle. There are no placebo controlled trials evaluating surgery for this condition.

- Steroid injections

Peritendinous steroid injections may provide short-term relief (up to 12 weeks), but result in increased pain and recurrence at one year (level 1)[37] Side effects are common, with pain in 50% and skin atrophy in 20 – 30%

| Complete recovery or much improvement at | Normal | Steroid | Physio | Steroid+Physio |

| 4 weeks | 10% | 71% | 39% | 68% |

| 26 weeks | 83% | 56% | 89% | 54% |

| 52 weeks | 93% | 84% | 100% | 82% |

| recurrence at 52w | 20% | 55% | 5% | 54% |

- Stretching

Stretching is not recommended due to the compressive loads placed on the tendon. Stretching also causes disuse of the supinator and wrist extensor muscles.

- Acupuncture

Article Downloads

File:Coombes2015 Management of Lateral Elbow Tendinopathy.pdf

See Also

References

- ↑ 1.0 1.1 Shiri R, Viikari-Juntura E, Varonen H, Heliövaara M. Prevalence and determinants of lateral and medial epicondylitis: a population study. Am J Epidemiol. 2006;164(11):1065-1074. doi:10.1093/aje/kwj325

- ↑ Walker-Bone K et al. Prevalence and impact of musculoskeletal disorders of the upper limb in the general population. Arthritis Rheum. 2004;51:642-651.

- ↑ Hatch GF 3rd, Pink MM, Mohr KJ, Sethi PM, Jobe FW. The effect of tennis racket grip size on forearm muscle firing patterns. Am J Sports Med. 2006;34(12):1977-1983. doi:10.1177/0363546506290185

- ↑ Smidt N, Lewis M, VAN DER Windt DA, Hay EM, Bouter LM, Croft P. Lateral epicondylitis in general practice: course and prognostic indicators of outcome. J Rheumatol. 2006;33(10):2053-2059.

- ↑ Haahr JP et al. Prognostic factors in lateral epicondylitis: a randomized trial with one-year follow-up in 266 new cases treated with minimal occupational intervention or the usual approach in general practice. Rheumatology (Oxford). 2003;42:1216-1225

- ↑ Smidt N et al. Lateral epicondylitis in general practice: course and prognostic indicators of outcome. J Rheumatol. 2006;33:2053-2059

- ↑ Berglund KM et al. Prevalence of pain and dysfunction in the cervical and thoracic spine in persons with and without lateral elbow pain. Man Ther. 2008;13:295-299

- ↑ Smidt N et al. Lateral epicondylitis in general practice: course and prognostic indicators of outcome. J Rheumatol. 2006;33:2053-2059

- ↑ Coombes BK et al. Cold hyperalgesia associated with poorer prognosis in lateral epicondylalgia: a 1-year prognostic study of physical and psychological factors. Clin J Pain. 2015;31:30-35.

- ↑ Fernández-Carnero J et al. Widespread mechanical pain hypersensitivity as sign of central sensitization in unilateral epicondylalgia: a blinded, controlled study. Clin J Pain. 2009;25:555-561.

- ↑ Coombes BK et al. Thermal hyperalgesia distinguishes those with severe pain and disability in unilateral lateral epicondylalgia. Clin J Pain. 2012;28:595-601.

- ↑ Coombes BK, Bisset L, Vicenzino B. Cold hyperalgesia associated with poorer prognosis in lateral epicondylalgia: a 1-year prognostic study of physical and psychological factors. Clin J Pain. 2015;31:30-35.

- ↑ Bisset L et al. Conservative treatments for tennis elbow—do subgroups of patients respond differently? Rheumatology (Oxford). 2007;46:1601-1605.

- ↑ Smidt N et al. Lateral epicondylitis in general practice: course and prognostic indicators of outcome. J Rheumatol. 2006;33:2053-2059.

- ↑ Fairbank SM, Corlett RJ. The role of the extensor digitorum communis muscle in lateral epicondylitis. J Hand Surg Br. 2002;27(5):405-409. doi:10.1054/jhsb.2002.0761

- ↑ Bisset LM, Russell T, Bradley S, Ha B, Vicenzino BT. Bilateral sensorimotor abnormalities in unilateral lateral epicondylalgia. Arch Phys Med Rehabil. 2006;87(4):490-495. doi:10.1016/j.apmr.2005.11.029

- ↑ Chard MD, Cawston TE, Riley GP, Gresham GA, Hazleman BL. Rotator cuff degeneration and lateral epicondylitis: a comparative histological study. Ann Rheum Dis 1994; 53:30-34

- ↑ Regan W, Wold LE, Coonrad RW, Morrey BF. Microscopic histopathology of chronic refractory lateral epicondylitis. Am J Sports Med 1992; 20:746-749.

- ↑ Maffulli N, Regine R, Carrillo F, Capasso G, Minelli S. Tennis elbow: an ultrasonographic study in tennis players. Br J Sports Med 1990; 24:151-155.

- ↑ Zeisig E, Ohberg L, Alfredson H. Extensor origin vascularity related to pain in patients with Tennis elbow. Knee Surg Sports Traumatol Arthrosc. 2006;14(7):659-663. doi:10.1007/s00167-006-0060-7

- ↑ Andersson G, Forsgren S, Scott A, et al. Tenocyte hypercellularity and vascular proliferation in a rabbit model of tendinopathy: contralateral effects suggest the involvement of central neuronal mechanisms. Br J Sports Med. 2011;45(5):399-406. doi:10.1136/bjsm.2009.068122

- ↑ Pasternack I et al. MR findings in humeral epicondylitis. A systematic review. Acta Radiol. 2001;42:434-440.

- ↑ Heales LJ et al. Diagnostic ultrasound imaging for lateral epicondylalgia: a case–control study. Med Sci Sports Exerc. 2014;46:2070-2076.

- ↑ Clarke AW et al. Lateral elbow tendinopathy: correlation of ultrasound findings with pain and functional disability. Am J Sports Med. 2010;38:1209-1214.

- ↑ Palmer K, Walker-Bone K, Linaker C, et al. The Southampton examination schedule for the diagnosis of musculoskeletal disorders of the upper limb. Ann Rheum Dis. 2000;59(1):5-11. doi:10.1136/ard.59.1.5

- ↑ [Wainner RS et al. Reliability and diagnostic accuracy of the clinical examination and patient self-report measures for cervical radiculopathy. Spine (Phila Pa 1976). 2003;28:52-62.

- ↑ Pattanittum P et al. Non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs) for treating lateral elbow pain in adults. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2013;5

- ↑ Paoloni JA et al. Randomised, double-blind, placebo-controlled clinical trial of a new topical glyceryl trinitrate patch for chronic lateral epicondylosis. Br J Sports Med. 2009;43:299-302.

- ↑ de Vos RJ et al. Autologous growth factor injections in chronic tendinopathy: a systematic review. Br Med Bull. 2010;95:63-77; Krogh TP et al. Treatment of lateral epicondylitis with platelet-rich plasma, glucocorticoid, or saline: a randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled trial. Am J Sports Med. 2013;41:625-635.

- ↑ Smidt N, Assendelft WJ, Arola H, et al. Effectiveness of physiotherapy for lateral epicondylitis: a systematic review. Ann Med. 2003;35(1):51-62. doi:10.1080/07853890310004138

- ↑ Cullinane FL, Boocock MG, Trevelyan FC. Is eccentric exercise an effective treatment for lateral epicondylitis? A systematic review. Clin Rehabil. 2014;28(1):3-19. doi:10.1177/0269215513491974

- ↑ Croisier JL, Foidart-Dessalle M, Tinant F, Crielaard JM, Forthomme B. An isokinetic eccentric programme for the management of chronic lateral epicondylar tendinopathy. Br J Sports Med. 2007;41(4):269-275. doi:10.1136/bjsm.2006.033324

- ↑ Tyler TF, Thomas GC, Nicholas SJ, McHugh MP. Addition of isolated wrist extensor eccentric exercise to standard treatment for chronic lateral epicondylosis: a prospective randomized trial. J Shoulder Elbow Surg. 2010;19(6):917-922. doi:10.1016/j.jse.2010.04.041

- ↑ Day et al.. A COMPREHENSIVE REHABILITATION PROGRAM FOR TREATING LATERAL ELBOW TENDINOPATHY. International journal of sports physical therapy 2019. 14:818-829. PMID: 31598419. Full Text.

- ↑ Kazi, Fatimah; Patil, Deepali S (2023-10-10). "Effects of the Tyler Twist Technique Versus Active Release Technique on Pain and Grip Strength in Patients With Lateral Epicondylitis". Cureus (in English). doi:10.7759/cureus.46799. ISSN 2168-8184. PMC 10634653. PMID 37954758.CS1 maint: PMC format (link)

- ↑ Karjalainen TV, Silagy M, O'Bryan E, Johnston RV, Cyril S, Buchbinder R. Autologous blood and platelet-rich plasma injection therapy for lateral elbow pain. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2021 Sep 30;9(9):CD010951. doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD010951.pub2. PMID: 34590307; PMCID: PMC8481072.

- ↑ Coombes BK et al. Efficacy and safety of corticosteroid injections and other injections for management of tendinopathy: a systematic review of randomised controlled trials. Lancet. 2010;376:1751-1767.

Literature Review

- Reviews from the last 7 years: review articles, free review articles, systematic reviews, meta-analyses, NCBI Bookshelf

- Articles from all years: PubMed search, Google Scholar search.

- TRIP Database: clinical publications about evidence-based medicine.

- Other Wikis: Radiopaedia, Wikipedia Search, Wikipedia I Feel Lucky, Orthobullets,