Nociplastic Pain: Difference between revisions

No edit summary |

No edit summary |

||

| Line 44: | Line 44: | ||

==Clinical Features== | ==Clinical Features== | ||

===Examination Findings=== | ===Examination Findings=== | ||

There is no specific clinical test for central sensitisation. Clinical suspicion may be raised with persistent, spontaneous, and widespread pain, or with severe and prolonged pain following a seemingly innocuous stimulus.{{#pmid: | There is no specific clinical test for central sensitisation. Clinical suspicion may be raised with persistent, spontaneous, and widespread pain, or with severe and prolonged pain following a seemingly innocuous stimulus.{{#pmid:33131390|griensven}} | ||

;Quantitative Sensory Testing | ;Quantitative Sensory Testing | ||

| Line 92: | Line 92: | ||

{{Reliable sources}} | {{Reliable sources}} | ||

[[Category:Physiology]] | [[Category:Physiology]] | ||

[[Category:Stubs]] | [[Category:Stubs]] | ||

[[Category:Widespread]] | [[Category:Widespread]] | ||

Revision as of 05:57, 31 March 2021

Musculoskeletal conditions can cause not only localised pain as a direct result from the condition, but also chronic widespread pain. This phenomenon has many terms with subtle differences in meaning, including central sensitisation, and nociplastic pain.[1]

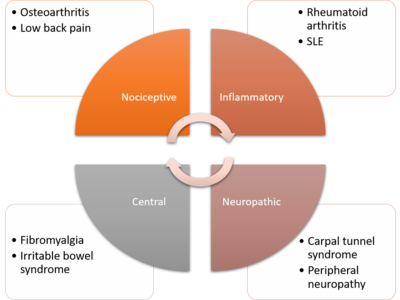

Central sensitisation is found in 10 to 40 percent of those with osteoarthritis, rheumatoid arthritis, spondyloarthritis, psoriatic arthritis, and systemic lupus erythematosus. It is also common in chronic trauma-induced low back and neck pain, complex regional pain syndrome, joint hypermobility syndrome, lateral elbow tendinopathy, and carpal tunnel syndrome. It is also thought to be a pain mechanism in fibromyalgia and other related chronic pain conditions, such as irritable bowel syndrome, bladder pain syndrome, and temporomandibular dysfunction.[1]

Epidemiology

The prevalence of chronic pain in New Zealand, when defined as lasting for 6 months or longer, was measured at 16.9% in 2011. Prevalence increased with age and economic deprivation. Pacific and Asian peoples had lower rates of chronic pain than European/other.[2] Around one fifth of people with chronic pain have predominantly neuropathic pain.[citation needed] Neuropathic pain is more disabling than other forms of pain and is associated with a lower quality of life.[citation needed]

Definitions

The IASP definitions of pain can be found on their website.

- IASP Definition of Pain

The IASP definition of pain was recently updated in 2020.[3]

“An unpleasant sensory and emotional experience associated with, or resembling that associated with, actual or potential tissue damage”

—IASP Definition of Pain 2020

- Sensitisation

Increased responsiveness of nociceptive neurons to their normal input, and/or recruitment of a response to normally subthreshold inputs...a neurophysiological term, may only be inferred indirectly from phenomena such as hyperalgesia or allodynia

- Central Sensitisation

Woolf discussed the differences between pain versus pathology versus "pain syndromes."[4] The central component of post-injury pain hypersensitivity was first termed sensitisation in 1987.[5]

“Any sensory experience greater in amplitude, duration and spatial extent than that would be expected from a defined peripheral input under normal circumstances qualifies as potentially reflecting a central amplification due to increased excitation or reduced inhibition. These changes could include a reduction in threshold, exaggerated response to a noxious stimulus, pain after the end of a stimulus, and a spread of sensitivity to normal tissue”

—Woolf 2011

The IASP define central sensitisation as follows:

“Increased responsiveness of nociceptive neurons in the central nervous system to their normal or subthreshold afferent input.”

—IASP

- Peripheral sensitisation

Increase Responsiveness and reduced threshold of nociceptive neurons in the periphery to the stimulation of their receptive fields

- Nociceptive Pain

actual or threatened damage , non-neural tissue, activation of nociceptors.

- Neuropathic pain

Primary lesion or disease of the somatosensory nervous system.

Pain Mechanisms

Some patients with fibromyalgia actually have unrecognised small-fibre polyneuropathy (SFPN). Oaklander et al found SFPN in 41% of skin biopsies of patients diagnosed with fibromyalgia, compared to 3% of controls. This is a disease that causes dysfunction and degeneration of peripheral small-fibre neurons, and is a biologically plausible cause for chronic widespread pain. [6]

Anatomical and Functional Changes

Clinical Features

Examination Findings

There is no specific clinical test for central sensitisation. Clinical suspicion may be raised with persistent, spontaneous, and widespread pain, or with severe and prolonged pain following a seemingly innocuous stimulus.[7]

- Quantitative Sensory Testing

A surrogate marker is quantitative sensory testing (QST). QST evaluates sensitivity to a variety of stimuli with respect to heightened responsiveness. Secondary hyperalgesia (increased sensitivity to pain in normal tissue away from the painful site) can be evaluated by applying a nociceptive stimulus to an area that is innervated by a different segmental level. Tertiary hyperalgesia (increased sensitivity to pain on the contralateral side to the painful site) has been described in several conditions (e.g. knee osteoarthritis), and so the contralateral side to the painful site may not be a good control. QST values are best compared to normal reference values if available. QST is a surrogate measure, as it does not evaluate spontaneous pain, and only assesses superficial sensitivity rather than deep pain. See figure for clinical correlates.

- Dynamic Mechanical Allodynia

Dynamic mechanical allodynia is assessed by brushing the skin. Allodynia can be a sign of central sensitisation but can also be caused by peripheral drivers.

- Temporal Summation

This is examined by applying a repeated nociceptive stimulus (e.g. sharpness) within the same area. An increasing response is positive.

- Spatial Summation

This refers to an increased pain intensity with stimulation of increasingly wide areas, such as with pin prick.

- Conditioned Pain Modulation

Refers to one noxious stimulus inhibiting another. This is difficult to interpret.

Questionnaires

The Central Sensitization Inventory and Pain Sensitivity Questionnaire have questionable construct validity. They are not associated with widespread pain sensitivity, and so should not be used as such. They are more correlated with resilience, anxiety, and negative affect. [8] It is important to remember that psychological distress is not synonymous with central sensitisation. Chronic pain can lead to secondary psychological distress (the distress of which can resolve if the pain resolves for example in successful radiofrequency neurotomy with whiplash injuries), and psychological distress can influence central sensitisation through descending modulation.[7]

Diagnosis

For several reasons, the clinician should be extremely careful with diagnosing "central sensitisation syndrome." Central sensitisation refers to a physiological process, and is not a diagnosis in itself. There are no highly validated tools for detecting this with questionnaires simply detecting psychological distress rather than pain sensitivity, and various examination findings having important limitations. It is important to not conflate psychological distress with central sensitisation. Peripheral pain drivers should always be considered as these can initiation, modulate, and maintain central sensitisation. Even in CRPS local anaesthetic blocks can temporarily abolish allodynia and spontaneous pain. Central processes can resolve with removal of a peripheral driver such as replacing an arthritic joint.[7]

The clinician should always have Epistemic Humility.[7] Our current understanding is evolving, and the tools for detecting both peripheral and central drivers have real limitations. Central conditions tend to be diagnosed by "committee criteria," i.e. a list of variably objective criteria with the final proviso being that other causes have been ruled out. I.e. it is when specific conditions are ruled out, not when the central condition has been ruled in. If the list of conditions to rule out is incomplete then the whole framework is wrong. Fibromyalgia was previously thought as being primarily a process driven by central sensitisation, but a large proportion of fibromyalgia patients actually have small fibre neuropathy on punch biopsy. I.e. for these patients they actually have a neurological disease, and many have been incorrectly told that their pain is central.[9] Another example is the controversial term "non-specific chronic low back pain" (NSCLBP). Patients may be incorrectly diagnosed with NSCLBP (and resulting treatment being directed at postulated central processes) despite the fact that peripheral sources have not been ruled out using validated measures such as medial branch blocks for facet joint mediated pain.

Furthermore, it is important for the clinician to remember that many tools of diagnosis such as MRI do not have perfect inter-observer reliability. An example of this is some radiologists in New Zealand not reporting on lumbar spine lateral recess stenosis in radicular pain syndromes, and so the patient with lateral recess stenosis and radicular pain may incorrectly be labelled as having pain due to a central process.

Management

Prognosis

- Osteoarthritis: In patients with osteoarthritis of the knee or hip who undergo joint replacement, chronic widespread pain (CWP) correlates with poorer pain outcomes, and increased analgesic use.[1]

- Autoimmune and inflammatory rheumatological conditions: CWP is correlated with increased pain and worse outcomes when measured by self-report questionnaires.[1]

- Chronic low back pain: CWP is present in 25% of patients, and correlated with greater disability.[1]

- Chronic neck pain: CWP at one month post neck injury is correlated with poor outcomes at 6 months.[1]

- Carpal tunnel syndrome: worse outcomes with CWP[1]

- Shoulder pain: worse outcomes with CWP[1]

- Lateral elbow tendinopathy: Worse outcomes with CWP[1]

Key Articles

- Media:Cohen2016 - nociplastic pain third mechanistic descriptor.pdf

- Media:Woolf2011 - Central sensitisation.pdf

- Media:Woolf2014 - Nociceptive amplification naming.pdf

- Media:Yunus2008 - Central sensitivity syndrome.pdf

References

- ↑ 1.0 1.1 1.2 1.3 1.4 1.5 1.6 1.7 1.8 Goldenberg, D et al. Overview of chronic widespread (centralized) pain in the rheumatic diseases. In: UpToDate, Post, TW (Ed), UpToDate, Waltham, MA, Jan 23 2020.

- ↑ Dominick et al.. Patterns of chronic pain in the New Zealand population. The New Zealand medical journal 2011. 124:63-76. PMID: 21946879.

- ↑ International Association for the Study of Pain (2020) IASP’s New Definition of Pain. Available at: https://www.iasp-pain.org/PublicationsNews/NewsDetail.aspx?ItemNumber=10475 (accessed 27 July 2020).

- ↑ Woolf. Central sensitization: implications for the diagnosis and treatment of pain. Pain 2011. 152:S2-15. PMID: 20961685. DOI. Full Text.

- ↑ Woolf et al.. Prolonged primary afferent induced alterations in dorsal horn neurones, an intracellular analysis in vivo and in vitro. Journal de physiologie 1988. 83:255-66. PMID: 3272296.

- ↑ Oaklander et al.. Objective evidence that small-fiber polyneuropathy underlies some illnesses currently labeled as fibromyalgia. Pain 2013. 154:2310-6. PMID: 23748113. DOI. Full Text.

- ↑ 7.0 7.1 7.2 7.3 van Griensven et al.. Central Sensitization in Musculoskeletal Pain: Lost in Translation?. The Journal of orthopaedic and sports physical therapy 2020. 50:592-596. PMID: 33131390. DOI.

- ↑ Coronado & George. The Central Sensitization Inventory and Pain Sensitivity Questionnaire: An exploration of construct validity and associations with widespread pain sensitivity among individuals with shoulder pain. Musculoskeletal science & practice 2018. 36:61-67. PMID: 29751194. DOI. Full Text.

- ↑ Martínez-Lavín. Fibromyalgia and small fiber neuropathy: the plot thickens!. Clinical rheumatology 2018. 37:3167-3171. PMID: 30238382. DOI.

Literature Review

- Reviews from the last 7 years: review articles, free review articles, systematic reviews, meta-analyses, NCBI Bookshelf

- Articles from all years: PubMed search, Google Scholar search.

- TRIP Database: clinical publications about evidence-based medicine.

- Other Wikis: Radiopaedia, Wikipedia Search, Wikipedia I Feel Lucky, Orthobullets,