Causes and Sources of Chronic Low Back Pain

Chronic low back pain does not defy diagnosis. While the causes of acute low back pain are largely unknown, this is not the case for chronic low back pain, where a biomedical diagnosis is possible in the majority of cases.

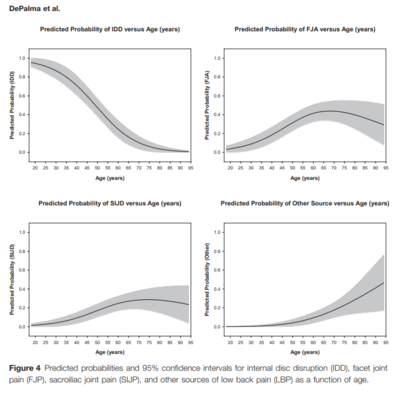

The exact figures depend on the age (figure 1), but around 40% have disc pain, around 10-30% have facet joint pain, and around 10-20% have sacroiliac joint pain.[2][3] Even using the worst case figures of diagnosable back pain based on 95% confidence intervals from one of the many studies yields 75% is diagnosable: 35% for disc + 24% for facet joint +13% for sacroiliac joint + 3% for miscellaneous conditions.[1] An example published worst case estimate using the lower end of the 95% confidence intervals from multiple studies is that 46% is diagnosable.[4]

Overview

The source of the pain refers to the anatomical structure which has nociceptive activity leading to pain perception. The cause of the pain is the disease process or disorder that is responsible for the nociceptive activity. The most well established causes of chronic low back pain are the lumbar intervertebral discs, and the lumbar zygapophysial joints.

Bogduk's postulates are analogous to Koch's postulates for bacterial diseases, and are the philosophical considerations concerning whether any structure can be deemed to be a credible cause of back pain:[3]

- Innervated: The structure should have a nerve supply.

- Experimental pain in normal volunteers: The structure should be capable of causing pain, similar to that seen clinically, ideally in normal volunteers, e.g. with noxious injection

- Pathology known: The structure should be susceptible to diseases or injuries that are known to be painful. Certain conditions however are not detectable using currently available imaging techniques, and in these cases the next line of evidence is used which is evidence from post-mortem studies or biomechanical studies, e.g. with facet joint pain.

- Identified in patients: The structure should be a source of pain in patients, using validated diagnostic techniques. Prevalence data can be determined here.

Following these postulates, it has been determined that the most common sources of chronic low back pain are the intervertebral disc, facet joint, and sacroiliac joint (table 1). Internal disc disruption fulfils postulates 1, 3, and 4. Sacroiliac joint and zygapophysial joint pain fulfils postulates 1, 2 and 4. These three diagnoses have survived copious scientific scrutiny. Interspinous ligament pain fulfils postulates 2-4, and probably fulfils the first postulate, but it is thought to be an uncommon cause.

| Study | Intervertebral Disc | Facet Joint | Sacroiliac Joint |

|---|---|---|---|

| DePalma 2011[1] | 41.8% (34.6 - 49.3) | 30.6% (24.2 - 37.9) | 18.2% (13.2 - 24.7) |

| Manchikanti 2020[5] | 34.1% (28.8 - 39.8) | ||

| Schwarzer 1995[6] | 39% (29 - 49) | ||

| Schwarzer 1995[7] | 32% (20 - 44) | ||

| Schwarzer 1994[8] | 15% | ||

| Schwarzer 1994[9] | 37% | ||

| Sembrano 2009[10] | 14.5% | ||

| Manchikanti 2008[11] | 18 - 44% | ||

| Irwin 2007[12] | 26.6% | ||

| Manchikanti 2001[13] | 30% adults, 52% elderly | ||

| Manchikanti 2004[14] | 31% (27 - 36) | ||

| Manchikanti 1999[15] | 45% (36 - 54) | ||

| Schwarzer 1995[16] | 30% (16-44) | ||

| Maigne 1996[17] | 18.5% |

Non-Specific Low Back Pain

- Main article: Non-Specific Chronic Low Back Pain

It is often incorrectly stated that the cause of low back pain cannot be diagnosed in 85% of cases with exact figure differing with different publications (some say 80%, some say 90%)[18] This "convenient truth" has been proven to be false time and time again. Unlike acute low back pain where the causes are largely unknown, The causes of chronic low back pain are largely known. History, examination, and radiography are insufficient for diagnosis, but the cause can be established with at least moderate certainty in around 90% of cases as long as there is access to appropriate investigations and the investigations are done in a logical manner.[19][20][21][22][23]

Red Flags

The red flag section in the acute low back pain article is still relevant for chronic low back pain.

Red flag conditions, such as tumours and infections are uncommon, if not rare causes of chronic low back pain. Bogduk provides the following for mathematical illustration:[4]

Pa% = prevalence of serious conditions in patients with acute back pain

Z% = the percentage of patients with a serious cause for acute low back pain that develop chronic low back pain

Pc% = Prevalence of serious condition in patients with chronic low back pain

Then if it is assumed that everyone with a serious condition develops chronic low back pain:

Pc% = (Pa/Z)%

E.g. tumours: P=1%, If 30% of acute patients become chronic, prevalence in chronic low back pain = (1/30)% = 3%

Discogenic Pain

Internal Disc Disruption

- See also: Internal Disc Disruption

The innervation of the disc is well documented (postulate 1), the pathology of internal disc disruption is also well documented (postulate 3), and validated diagnostic techniques exist in the form of provocation discography (postulate 4).

Internal disc disruption is a condition that affects lumbar intervertebral discs and is the cause of pain in around 40% of individuals with chronic low back pain. As a diagnostic concept it has the most research evidence amongst all causes of chronic low back pain.

The inciting event is fatigue failure of the vertebral endplate, which leads to degradation of the nuclear matrix. Subsequently radial and circumferential fissures develop that penetrate from the nucleus pulposus through to the anulus fibrosus, however the outer anulus is not breached. Pain is thought to arise through chemical nociception around the fissures ,as well as through mechanical nociception from the degraded nuclear matrix leading to greater loads being placed on the posterior anulus fibrosus.

Internal disc disruption can be diagnosed through provocation discography, post-discography CT, and imperfectly through MRI.

Discitis and Vertebral Osteomyelitis

Chemical nociception can occur with irritation of the nociceptive fibres of an infected disc, and this is a red flag condition. The most common organism is Staphylococcus aureus which accounts for more than 50% of cases. Bacteria can enter a disc or vertebra through:

- Haematogenous spread form a distant site such as the genitourinary tract, skin, soft tissue, respiratory tract, intravascular devices, infective endocarditis, and dental infection. This is the most common cause.

- Direct inoculation from trauma, provocation discography, spinal surgery, or other procedures.

- Contiguous spread from adjacent soft tissue infection.

Torsion Injuries

With forcible rotation of a vertebra, the initial axis of rotation is about the posterior anulus which prestresses it. With further rotation there is impaction of a zygapophysial joint leading to an impaction microfracture which is one of the features. This impaction leads to a new axis of rotation which additionally laterally shears the anulus, and the combination of torsion and lateral shears causes an annular tear. Meanwhile, the opposite zygapophysial joint is distracted and there is an avulsion fracture or capsular tear. The risk is greater when rotation occurs in flexion due to flexion prestressing the anulus.

This is still an experimental entity with an unknown prevalence, and incompletely developed techniques for diagnosis. It can be diagnosed by a negative provocation discography, and then injecting contrast and local anaesthetic into the anulus which will relieve the pain and also show the tear on post-contrast CT imaging.[3]

Zygapophysial Joint Pain

- Main article: Lumbar Zygapophysial Joint Pain

Zygapophysial joints are innervated (postulate 1), they produce pain with noxious stimulation in normal volunteers (postulate 2), and there is validated diagnostic methodology in the form of controlled blocks (postulate 4). The pathology however is not completely known.

The prevalence of zygapophysial joint pain depends on the age group but is around 30%. In older individuals it is as common a cause as internal disc disruption.

Lumbar zygapophysial joint pain cannot be diagnosed through standard clinical means, nor through plain films, CT, or MRI. It can only be diagnosed by controlled diagnostic blocks.

Sacroiliac Joint Pain

- Main article: Sacroiliac Joint Pain

The innervation of the sacroiliac joint is well documented (postulate 1), studies in normal volunteers have shown noxious stimulation produces low back pain (postulate 2), and there is a validated diagnostic methodology in the form of controlled intraarticular blocks (postulate 4). The pathology may be degenerative changes, often precipitated by trauma,[24] but it is incompletely known.[3]

Prevalence studies based on diagnostic blocks yields a prevalence range of 13-19% (about 15%). It is an underappreciated source of chronic low back pain.[25]

Sacroiliac joint pain is generally perceived as low back, or buttock pain, felt below the L5 level. Some patients will have referred pain down the leg and into the foot. Fortin et al found a 3x10cm area, just inferior to PSIS, thought to be specific for SI joint pain.[26]

Disputed Causes of Pain

Degenerative Disc Disease

- Main article: Lumbar Degenerative Disc Disease

Degenerative disc disease is not a proven cause of pain. Internal disc disruption is a separate concept to disc degeneration. While there are many similar processes and features, internal disc disruption is a response to injury that occurs either through single or repetitive compressive loads.[27] Degenerative disc disease does not correlate strongly with back pain, unlike internal disc disruption. Genetics and aging play the main roles in its development.

Low Grade Disc Infection

A disputed cause is chronic low grade infection by Propionibacterium acnes. The hypothesis is that vertebral marrow/endplate oedema caused by low grade bacterial discitis

Some studies have isolated Cutibacterium (Propionibacterium) acnes from discs in people undergoing spinal surgery. A systematic review attempted to clarify this and found that this may be related to abnormal discs being more susceptible to infection, but it is difficult to establish true infection versus contamination (some studies also isolated CONS).[28]

In an RCT of 144 patients, there was significant improvement with 100 days of augmentin in chronic low back pain, prior disc herniation, and type 1 Modic changes. Limitations included high proportions of participants having had previous back surgery, no improvement in the control group, and unclear efficacy of blinding.[29]

A multi-centre double blinded RCT was done in an attempt to reproduce the results but it was not successful. See graphic[30]

Structural Abnormalities

Structural abnormalities include congenital abnormalities (congenital fusion, spina bifida occulta, and transitional vertebra), spondylolysis, spondylolisthesis, and spondylosis. As is the case for acute low back pain, these abnormalities are equally common in symptomatic and asymptomatic patients and so cannot be causes of chronic low back pain.[31]

For spondylolysis, only amongst sportspeople are pars defects more common. However simply seeing spondylolysis on plain films does not constitute having found the source of pain. For that a pars block is required, with relief of pain supporting the diagnosis, and predicts success with surgery.[32]

Instability

The term spinal instability is controversial. There are various biomechanical definitions and diagnostic criteria. The musculoskeletal medicine view is that instability does not constitute a diagnosis of chronic low back pain.

The various definitions, which all have limitations include:

- Loss of stiffness in spinal motion segments

- An increase in the neutral zone of intervertebral movements

- Increase in the ratio between the magnitude of translation and the magnitude of rotation that a motion segment exhibits during flexion-extension of the lumbar spine

Instability can also be classified based on the lesions that are postulated to cause the instability:

- Fractures and fracture-dislocations

- Infections of anterior elements

- Neoplasms

- Spondylolisthesis

- Degenerative

In this classification scheme for fractures, infections, and neoplasms one only needs to see the finding, and not demonstrate the instability biomechanically, which is sensible.

For spondylolisthesis, while it can look threatening on radiographs, it rarely progresses, and grade 1 and grade 2 spondylolisthesis is associated with reduced range of motion rather than instability. Further precision studies have shown that motion patterns of patients are indistinguishable from degenerative disc disease.

There are several types of instability that have been attributed to degeneration of the lumbar spine. However there have been no studies proving them as a cause of pain or showing that correcting them resolves pain. These types of instability include:

- Rotational – hypothetical entity, certain radiographic signs may suggest it, but the reliability and validity has not been studied.

- Retrolisthetic – occurs during extension, but this movement can occur in asymptomatic individuals.

- Translational – abnormal forward translation during flexion. There is difficulty in defining the upper limit of normal, with dynamic translations of 4mm occurring in 20% of asymptomatic individuals.

Failed back surgery syndrome

- Main article: Failed Back Surgery Syndrome

The pathology of the condition is unknown. Some hypotheses include neuroma formation, deafferentation, epidural scarring, etc. There are no reliable diagnostic techniques where these conjectures can be confirmed. This fact leads to the reason why the term "syndrome" is used, because patho-anatomical diagnosis is usually impossible.

Patients with FBSS can be further categorised into:

- Correct operation, wrong diagnosis e.g Solid L4-L5 discectomy and fusion but pain arising from L3-4 disc

- Correct diagnosis, wrong operation e.g L3-4 discogenic pain treated with a posterolateral fusion but no discectomy

- Wrong diagnosis, wrong operation e.g Laminectomy and discectomy for asymptomatic disc bulge but the source of pain was actually the zygoapophyseal joint

- A further subset of patients will have a new cause of pain following their procedure e.g Post-operative neuroma, arachnoiditis, nerve injury, epidural scarring, local irritation by a fusion mass/instrumentation

Correlations

- One method is to compare prevalence in people with and without pain. If prev is higher in people with pain, association is established

- Another method is to anesthetize joint. If relieves pain, target joint is implicated as source.

The prevalence of lumbar disc degeneration in asymptomatic individuals, clearly increases with age Radiographic features of cervical spine in asymptomatic people again increases with age (hardly any “normal” looking spines in over 50)

Neck Pain

Study compared patients with neck pain, with controls. There were no differences in prevalence of spondylosis, severe disc changes or facet joint changes between cases and controls. Degenerative changes in cervical discs/z joints do not correlate with pain

Low Back Pain

A large population study looked at osteoarthosis in the context of pain No association with pain, irrespective of grade Many studies on disc degeneration Systematic reviews on high quality studies showed no clinical association between degenerative disc changes and pain

Spondylolisthesis

- Spondylolithesis – translation of 1 vertebral body on another. 6 broad categories – (wiltse classification) isthmic, traumatic, degen, pathologic, dysplastic and post surgical. It can also be classified according to severity (Merding)

- Bogduk – not associated with pain, finding it on xray does not constitute diagnosis. Rarely progresses. Grade 1 – 2 associate with reduced ROM rather than instability.

Degenerative Lumbar Spondylolisthesis

- Incidence 19-43%, mean age 71, most common in females

- Most common L4/5

- Initial event – disc degeneration/narrowing of disc space - micro-instability

- Cause of pain multi factorial

- Most are grade 1 (75%) – less than 25% slip

- Average slip progression – 18%, no correlation between progression and symptoms

- Natural history and management of low grade slip is controversial, conservative management generally indicated. Surgery for refractory cases

Isthmic Lumbar Spondylolisthesis

- Isthmic meaning movement of one vertebrae on another, due to a defect in the pars, termed spondylolysis (unhealed stress fracture). Spondylolysis can be present without displacement. Spondylolistesis occurs in 40-60% of patients with bilateral spondylolysis (unlikely if unilateral).

- Most are asymptomatic, 25% have back/radicular pain

- Prevalence in children 2.6%, increasing to 4% in adult

- Asymptomatic in 3-11% of adults

- More common in men, L5/S1

- Causes are multifactorial, genetic component

- Back pain may be from micro-stability or pain from degenerative disc

- Symptomatic patients are initially treated non-operatively

High grade lumbar sponylolisthesis

- Defined as >50% slippage

- Most are at L5/S1, a result of isthmic spondylolisthesis

- Most have a degree of neurologic compromise

- Pain usually with hyperextension, resolves with time due to fracture union

- Treatment is focused on correction of lordosis and sagittal balance

- Natural history – difficult to predict if further slippage will occur

- Conservative management trialed in adolescence, usually unable to provide permanent relief�

Surgical vs Non Surgical Treatment of Lumbar Spondylolithesis – Karsy et al.

- Non operative effective in patients without neurogenic claudication or radiculopathy and stable spondylolisthesis (grade 1)

- 1/3 show progression over time

- Lumbar decompression alone can be effective for low grade, fusion if higher grade

- Mechanical instability is change of 3mm-6mm between flexion/ext films, or change from sitting to standing

- Meta analysis – surgical intervention is more effective than non operative, for patients with pain and functional limitations

Lumbar instability – J. Beazell

- Historical term, that has been debated through 1980-90’s

- Encompasses two types:

- Mechanical (radiographic)

- Functional (clinical)

- Topic is subject to much debate on exact nature of problem, correlation with history and relevance to patient management

Seminal Journal Articles

Degenerative Joint Disease of the Spine – N. Bogduk. Radiol Clin N Am 50 (2012) 613–628

High-Grade Lumbar Spondylolisthesis – A. Beck et al. Clin N Am 30 (2019) 291-298

Isthmic Lumbar Lumbar Spondylolisthesis – A. Bhalla. Clin N Am 30 (2019) 283-290

Degenerative Lumbar Spondylolisthesis – M. Bydon. Clin N Am 30 (2019) 299-304

Surgical vs Non Surgical Treatment of Lumbar Spondylolisthesis. Clin N Am 30 (2019) 333-340

Lumbar instability: an evolving and challenging concept. J. Beazell. Journal of Manual and Manpulative Therapy. Vol 18 1 (2010)

- ↑ 1.0 1.1 1.2 DePalma MJ, Ketchum JM, Saullo T. What is the source of chronic low back pain and does age play a role? Pain Med. 2011 Feb;12(2):224-33. doi: 10.1111/j.1526-4637.2010.01045.x. Epub 2011 Jan 25. PMID: 21266006.

- ↑ DePalma MJ. Diagnostic Nihilism Toward Low Back Pain: What Once Was Accepted, Should No Longer Be. Pain Med. 2015 Aug;16(8):1453-4. doi: 10.1111/pme.12850. Epub 2015 Jul 27. PMID: 26218010.

- ↑ 3.0 3.1 3.2 3.3 Bogduk. Low back pain In: Clinical and Radiological Anatomy of the Lumbar Spine. 5th Edition. Elsevier 2012

- ↑ 4.0 4.1 Bogduk and McGuirk. Causes and sources of chronic low back pain In: Medical Management of Acute and Chronic Low Back Pain. Elsevier 2002

- ↑ Manchikanti L, Kosanovic R, Pampati V, Cash KA, Soin A, Kaye AD, Hirsch JA. Low Back Pain and Diagnostic Lumbar Facet Joint Nerve Blocks: Assessment of Prevalence, False-Positive Rates, and a Philosophical Paradigm Shift from an Acute to a Chronic Pain Model. Pain Physician. 2020 Sep;23(5):519-530. PMID: 32967394.

- ↑ Schwarzer AC, Aprill CN, Derby R, Fortin J, Kine G, Bogduk N. The prevalence and clinical features of internal disc disruption in patients with chronic low back pain. Spine (Phila Pa 1976). 1995 Sep 1;20(17):1878-83. doi: 10.1097/00007632-199509000-00007. PMID: 8560335.

- ↑ Schwarzer AC, Wang SC, Bogduk N, McNaught PJ, Laurent R. Prevalence and clinical features of lumbar zygapophysial joint pain: a study in an Australian population with chronic low back pain. Ann Rheum Dis. 1995 Feb;54(2):100-6. doi: 10.1136/ard.54.2.100. PMID: 7702395; PMCID: PMC1005530.

- ↑ Schwarzer AC, Aprill CN, Derby R, Fortin J, Kine G, Bogduk N. Clinical features of patients with pain stemming from the lumbar zygapophysial joints. Is the lumbar facet syndrome a clinical entity? Spine (Phila Pa 1976). 1994 May 15;19(10):1132-7. doi: 10.1097/00007632-199405001-00006. PMID: 8059268.

- ↑ Schwarzer AC, Aprill CN, Derby R, Fortin J, Kine G, Bogduk N. The false-positive rate of uncontrolled diagnostic blocks of the lumbar zygapophysial joints. Pain. 1994 Aug;58(2):195-200. doi: 10.1016/0304-3959(94)90199-6. PMID: 7816487.

- ↑ Sembrano JN, Polly DW Jr. How often is low back pain not coming from the back? Spine (Phila Pa 1976). 2009 Jan 1;34(1):E27-32. doi: 10.1097/BRS.0b013e31818b8882. PMID: 19127145.

- ↑ Manchikanti L, Manchikanti KN, Cash KA, Singh V, Giordano J. Age-related prevalence of facet-joint involvement in chronic neck and low back pain. Pain Physician. 2008 Jan;11(1):67-75. PMID: 18196171.

- ↑ Irwin RW, Watson T, Minick RP, Ambrosius WT. Age, body mass index, and gender differences in sacroiliac joint pathology. Am J Phys Med Rehabil. 2007 Jan;86(1):37-44. doi: 10.1097/phm.0b013e31802b8554. PMID: 17304687.

- ↑ Manchikanti L, Pampati V, Rivera J, Fellows B, Beyer C, Damron K. Role of facet joints in chronic low back pain in the elderly: a controlled comparative prevalence study. Pain Pract. 2001 Dec;1(4):332-7. doi: 10.1046/j.1533-2500.2001.01034.x. PMID: 17147574.

- ↑ Manchikanti L, Boswell MV, Singh V, Pampati V, Damron KS, Beyer CD. Prevalence of facet joint pain in chronic spinal pain of cervical, thoracic, and lumbar regions. BMC Musculoskelet Disord. 2004 May 28;5:15. doi: 10.1186/1471-2474-5-15. PMID: 15169547; PMCID: PMC441387.

- ↑ Manchikanti L, Pampati V, Fellows B, Bakhit CE. Prevalence of lumbar facet joint pain in chronic low back pain. Pain Physician. 1999 Oct;2(3):59-64. PMID: 16906217.

- ↑ Schwarzer AC, Aprill CN, Bogduk N. The sacroiliac joint in chronic low back pain. Spine (Phila Pa 1976). 1995 Jan 1;20(1):31-7. doi: 10.1097/00007632-199501000-00007. PMID: 7709277.

- ↑ Maigne JY, Aivaliklis A, Pfefer F. Results of sacroiliac joint double block and value of sacroiliac pain provocation tests in 54 patients with low back pain. Spine (Phila Pa 1976). 1996 Aug 15;21(16):1889-92. doi: 10.1097/00007632-199608150-00012. PMID: 8875721.

- ↑ Fitzcharles MA, Cohen SP, Clauw DJ, Littlejohn G, Usui C, Häuser W. Nociplastic pain: towards an understanding of prevalent pain conditions. Lancet. 2021 May 29;397(10289):2098-2110. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(21)00392-5. PMID: 34062144.

- ↑ DePalma et al.. What is the source of chronic low back pain and does age play a role?. Pain medicine (Malden, Mass.) 2011. 12:224-33. PMID: 21266006. DOI.

- ↑ DePalma et al.. Etiology of chronic low back pain in patients having undergone lumbar fusion. Pain medicine (Malden, Mass.) 2011. 12:732-9. PMID: 21481166. DOI.

- ↑ DePalma et al.. Multivariable analyses of the relationships between age, gender, and body mass index and the source of chronic low back pain. Pain medicine (Malden, Mass.) 2012. 13:498-506. PMID: 22390231. DOI.

- ↑ DePalma et al.. Structural etiology of chronic low back pain due to motor vehicle collision. Pain medicine (Malden, Mass.) 2011. 12:1622-7. PMID: 21958329. DOI.

- ↑ DePalma. Diagnostic Nihilism Toward Low Back Pain: What Once Was Accepted, Should No Longer Be. Pain medicine (Malden, Mass.) 2015. 16:1453-4. PMID: 26218010. DOI.

- ↑ Murakami, E. (2019). Pathophysiology of Sacroiliac Joint Disorder BT - Sacroiliac Joint Disorder: Accurately Diagnosing Low Back Pain. In E. Murakami (Ed.) (pp. 33–53)

- ↑ Bogduk et al. Medical Management of Acute and Chronic Low Back Pain. 2002. Elsevier.

- ↑ Fortin JD, Dwyer AP, West S, Pier J. Sacroiliac joint: pain referral maps upon applying a new injection/arthrography technique. Part I: Asymptomatic volunteers.Spine (Phila Pa 1976). 1994;19(13):1475-1482.

- ↑ Bogduk N, Aprill C, Derby R. Lumbar discogenic pain: state-of-the-art review. Pain Med. 2013 Jun;14(6):813-36. doi: 10.1111/pme.12082. Epub 2013 Apr 8. PMID: 23566298.

- ↑ Urquhart DM et al. Could low grade bacterial infection contribute to low back pain? A systematic review.BMC Med 2015;13:13.

- ↑ Albert H, Sorensen J, Christensen B, Manniche C. Antibiotic treatment in patients with chronic low back pain and vertebral bone edema (Modic type 1 changes): a double-blind randomized clinical controlled trial of efficacy.Eur Spine J.2013;22:697–707

- ↑ Bråten LCH, Rolfsen MP, Espeland A, et al. Efficacy of antibiotic treatment in patients with chronic low back pain and Modic changes (the AIM study): double blind, randomised, placebo controlled, multicentre trial [published correction appears in BMJ. 2020 Feb 11;368:m546]. BMJ. 2019;367:l5654. Published 2019 Oct 16. doi:10.1136/bmj.l5654

- ↑ van Tulder MW, Assendelft WJ, Koes BW, Bouter LM. Spinal radiographic findings and nonspecific low back pain. A systematic review of observational studies. Spine (Phila Pa 1976). 1997 Feb 15;22(4):427-34. doi: 10.1097/00007632-199702150-00015. PMID: 9055372.

- ↑ Suh PB, Esses SI, Kostuik JP. Repair of pars interarticularis defect. The prognostic value of pars infiltration. Spine (Phila Pa 1976). 1991 Aug;16(8 Suppl):S445-8. PMID: 1785102.