Chronic Low Back Pain: Difference between revisions

No edit summary |

No edit summary |

||

| Line 1: | Line 1: | ||

{{stub}} | {{stub}} | ||

Chronic low back pain is a common cause of persistent suffering and disability for the affected individual, but also has significant effects on those around them. The biomedical assessment involves determining whether they have the IASP definition of low back pain, whether it is indeed chronic, ascertaining whether they have referred pain and whether it is somatic referred pain or radicular pain, and identifying "red flag" conditions. A decision is then made about whether to go down an investigative pathway to determine the source and cause of the pain. Treatment approaches include monotherapies (e.g. physiotherapy, surgery, medication), multi-disciplinary treatments, and reductionist treatments if a precision diagnosis is made and a relevant treatment is available, efficacious, and acceptable to the patient (e.g. medial branch radiofrequency neurotomy for confirmed facet joint pain). | |||

==Definitions== | ==Definitions== | ||

| Line 5: | Line 6: | ||

=== Topography === | === Topography === | ||

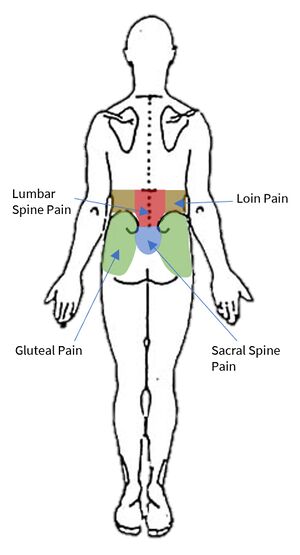

Starting with the wrong definition of low back pain can lead to the wrong diagnosis, and so it is important to be clear here. The IASP taxonomy categorises low back pain into lumbar spinal pain and sacral spinal pain. There is also an overlapping definition called lumbosacral pain. These three categories constitute the colloquial term "low back pain." | Starting with the wrong definition of low back pain can lead to the wrong diagnosis, and so it is important to be clear here. Low back pain is not loin pain, nor is it gluteal pain. The IASP taxonomy categorises low back pain into lumbar spinal pain and sacral spinal pain. There is also an overlapping definition called lumbosacral pain. These three categories constitute the colloquial term "low back pain." | ||

Lumbar spinal pain is pain in a region bounded superiorly by an imaginary transverse line through the tip T12, inferiorly by an imaginary transverse line through the tip of S1, and laterally by vertical lines tangential to the lateral | Lumbar spinal pain is pain in a region bounded superiorly by an imaginary transverse line through the tip T12, inferiorly by an imaginary transverse line through the tip of S1, and laterally by vertical lines tangential to the lateral margins of the erector spinae muscles. | ||

Sacral Spinal Pain is pain in a region bounded superiorly by an imaginary transverse line through the tip of S1, inferiorly by an imaginary transverse line through the posterior sacrococcygeal joints, and laterally by imaginary lines passing through the posterior superior and posterior inferior iliac spines." | Sacral Spinal Pain is pain in a region bounded superiorly by an imaginary transverse line through the tip of S1, inferiorly by an imaginary transverse line through the posterior sacrococcygeal joints, and laterally by imaginary lines passing through the posterior superior and posterior inferior iliac spines." | ||

| Line 24: | Line 25: | ||

[[Lumbar Radicular Pain|Radicular pain]] is a subset of [[Neuropathic Pain|neuropathic pain]], and refers to pain that is evoked with stimulation of the nerve roots or dorsal root ganglion of a spinal nerve. In radicular pain, the pain is felt in the peripheral innervation of the affected nerve. | [[Lumbar Radicular Pain|Radicular pain]] is a subset of [[Neuropathic Pain|neuropathic pain]], and refers to pain that is evoked with stimulation of the nerve roots or dorsal root ganglion of a spinal nerve. In radicular pain, the pain is felt in the peripheral innervation of the affected nerve. | ||

== Aetiology | Somatic referred pain and radicular pain can usually be differentiated based on the quality and spread of the pain, see the assessment section below. | ||

== Aetiology == | |||

{{Main|Causes and Sources of Chronic Low Back Pain}} | {{Main|Causes and Sources of Chronic Low Back Pain}} | ||

Various structures in the low back are capable of nociception as determined through noxious stimulation, including the muscles, interspinous ligaments, zygapophysial joints, sacroiliac joints, and the intervertebral discs which are the most sensitive. These constitute possible ''sources'' of pain.<ref>Wade King and Nikolai Bogduk. Chronic Low Back Pain In: Bonica's Management of Pain. 2018</ref> | |||

As for the causes, the lumbar intervertebral discs and lumbar zygapophysial joints have the most evidence as established causes. The sacroiliac joint has the next best evidence. The prevalence depends on the age, but around 40% have disc pain, around 30% have facet joint pain, and around 20% have sacroiliac joint pain.<ref>DePalma MJ. Diagnostic Nihilism Toward Low Back Pain: What Once Was Accepted, Should No Longer Be. Pain Med. 2015 Aug;16(8):1453-4. doi: 10.1111/pme.12850. Epub 2015 Jul 27. PMID: 26218010.</ref> The common aphorism that "most low back pain is non-specific" is false. | |||

== Assessment == | |||

{{Somatic Referred vs Radicular Pain}} | |||

== Management == | == Management == | ||

Revision as of 19:03, 6 September 2021

Chronic low back pain is a common cause of persistent suffering and disability for the affected individual, but also has significant effects on those around them. The biomedical assessment involves determining whether they have the IASP definition of low back pain, whether it is indeed chronic, ascertaining whether they have referred pain and whether it is somatic referred pain or radicular pain, and identifying "red flag" conditions. A decision is then made about whether to go down an investigative pathway to determine the source and cause of the pain. Treatment approaches include monotherapies (e.g. physiotherapy, surgery, medication), multi-disciplinary treatments, and reductionist treatments if a precision diagnosis is made and a relevant treatment is available, efficacious, and acceptable to the patient (e.g. medial branch radiofrequency neurotomy for confirmed facet joint pain).

Definitions

- Main article: Low Back Pain Definitions

Topography

Starting with the wrong definition of low back pain can lead to the wrong diagnosis, and so it is important to be clear here. Low back pain is not loin pain, nor is it gluteal pain. The IASP taxonomy categorises low back pain into lumbar spinal pain and sacral spinal pain. There is also an overlapping definition called lumbosacral pain. These three categories constitute the colloquial term "low back pain."

Lumbar spinal pain is pain in a region bounded superiorly by an imaginary transverse line through the tip T12, inferiorly by an imaginary transverse line through the tip of S1, and laterally by vertical lines tangential to the lateral margins of the erector spinae muscles.

Sacral Spinal Pain is pain in a region bounded superiorly by an imaginary transverse line through the tip of S1, inferiorly by an imaginary transverse line through the posterior sacrococcygeal joints, and laterally by imaginary lines passing through the posterior superior and posterior inferior iliac spines."

Lumbosacral Pain is pain perceived as arising from a region encompassing or centred over the lower third of the lumbar region as described above and the upper third of the sacral region as described above.

Acuity

Chronic pain is pain present for longer than 3 months (91 days). One pragmatic approach is to include in the definition of chronic those patients with acute low back pain who are not improving when it may not be sensible to wait until the 91 day mark, say at two months. However if they have had pain for more than two months and not had evidence based management for acute low back pain then they should have that first. Indeed, following the acute approach may still be appropriate for some patients who have had pain for longer than 3 months.

Referred Pain

- Main article: Low_Back_Pain_Definitions#Referred_Pain

Referred pain is "pain perceived as arising or occurring in a region of the body innervated by nerves or branches of nerves other than those that innervate the actual source of pain"

Visceral referred pain is referred pain where the source lies in an organ or blood vessel of the body. With low back pain, the uterus and abdominal aorta are important considerations. Other viscera with higher segmental supply may cause back pain such as pancreatitis, but this may be due to irritation of the posterior abdominal wall, in which case the pain is not truly referred in nature.

Somatic referred pain is referred pain where the source originates in a tissue or structure of the body wall or limbs. A number of structures in the lumbar spine are capable of nociception including the lumbar zygapophysial joints, intervertebral discs, sacroiliac joints, and more.

Radicular pain is a subset of neuropathic pain, and refers to pain that is evoked with stimulation of the nerve roots or dorsal root ganglion of a spinal nerve. In radicular pain, the pain is felt in the peripheral innervation of the affected nerve.

Somatic referred pain and radicular pain can usually be differentiated based on the quality and spread of the pain, see the assessment section below.

Aetiology

- Main article: Causes and Sources of Chronic Low Back Pain

Various structures in the low back are capable of nociception as determined through noxious stimulation, including the muscles, interspinous ligaments, zygapophysial joints, sacroiliac joints, and the intervertebral discs which are the most sensitive. These constitute possible sources of pain.[1]

As for the causes, the lumbar intervertebral discs and lumbar zygapophysial joints have the most evidence as established causes. The sacroiliac joint has the next best evidence. The prevalence depends on the age, but around 40% have disc pain, around 30% have facet joint pain, and around 20% have sacroiliac joint pain.[2] The common aphorism that "most low back pain is non-specific" is false.

Assessment

| Somatic Referred | Radicular | |

|---|---|---|

| Pain quality | Dull, deep ache, or pressure-like, perhaps like an expanding pressure | Shooting, lancinating, or electric-shocks |

| Relation to back pain | Referred pain is always concurrent with back pain. If the back pain ceases then so does the referred pain. If the back pain flares then so does the leg pain intensity and spatial spread. | Not always concurrent with back pain. |

| Distribution | Anywhere in the lower limb, fixed in location, commonly in the buttock or proximal thigh. Spread of pain distal to the knee can occur when severe even to the foot, and it can skip regions such as the thigh. It can feel like an expanding pressure into the lower limb, but remains in location once established without traveling. It can wax and wane, but does so in the same location. | Entire length of lower limb, but below knee > above knee. In mild cases the pain may be restricted proximally. |

| Pattern | Felt in a wide area, with difficult to perceive boundaries, often demonstrated with an open hand rather than pointing finger. The centres in contrast can be confidently indicated. | Travels along a narrow band no more than 5-8 cm wide in a quasi-segmental fashion but not related to dermatomes (dynatomal). |

| Depth | Deep only, lacks any cutaneous quality | Deep as well as superficial |

| Neurological signs | Not characteristic | Favours radicular pain, but not required. |

| Neuroanatomical basis | Discharge of the peripheral nerve endings of Aδ and C fibres from the lower back converge onto second order neurons in the dorsal horn that also receive input from from the lower limb, and so the frontal lobe has no way of knowing where the pain came from. | Heterotopic discharge of Aδ, Aβ, and C fibres through stimulation of a dorsal root or dorsal root ganglion of a spinal nerve, typically in the presence of inflammation, with pain being felt in the peripheral innervation of the affected nerve |

Management

Laerum et al outlined what a "Good Back Consultation" entails, based on three interdisciplinary Norwedgian RCTs for chronic low back pain.[4]

- Take them seriously

- Examination: explanation during the exam (what was being done and what was found)

- Education: Providing an understandable explanation for the pain given with conviction (exact medical diagnosis is not essential) and addressing misconceptions. He uses a disc injury explanation.

- Reassurance: given with conviction, address fears but cognitive reassurance is preferred over emotional which can create dependency.

- Psychosocial discussion: deal with possible correlation (in both directions) between daily life, job, family, coping, quality of life aspects, role function and the LBP

- Treatment: Encourage normal activity and avoiding rest. Empower the patient to take responsibility for their own rehabilitation.

References

- ↑ Wade King and Nikolai Bogduk. Chronic Low Back Pain In: Bonica's Management of Pain. 2018

- ↑ DePalma MJ. Diagnostic Nihilism Toward Low Back Pain: What Once Was Accepted, Should No Longer Be. Pain Med. 2015 Aug;16(8):1453-4. doi: 10.1111/pme.12850. Epub 2015 Jul 27. PMID: 26218010.

- ↑ Bogduk et al. Medical Management of Acute and Chronic Low Back Pain: An Evidence Based Approach. Elsevier Science. 2002

- ↑ Laerum E, Indahl A, Skouen JS. What is "the good back-consultation"? A combined qualitative and quantitative study of chronic low back pain patients' interaction with and perceptions of consultations with specialists. J Rehabil Med. 2006 Jul;38(4):255-62. doi: 10.1080/16501970600613461. PMID: 16801209.