Lumbar Zygapophysial Joint Pain: Difference between revisions

(Created page with "== Anatomy == The lumbar zygapophysial joints are true synovial joints. They have hyaline cartilage that overlies the subchondral bone, a synovial membrane, a fibrous joint ca...") |

|||

| (19 intermediate revisions by 2 users not shown) | |||

| Line 1: | Line 1: | ||

== Anatomy == | {{Authors | ||

|Authors=Jeremy | |||

}} | |||

{{Condition | |||

|quality=Partial | |||

|image=Lumbar facet joints MRI oedema.jpg | |||

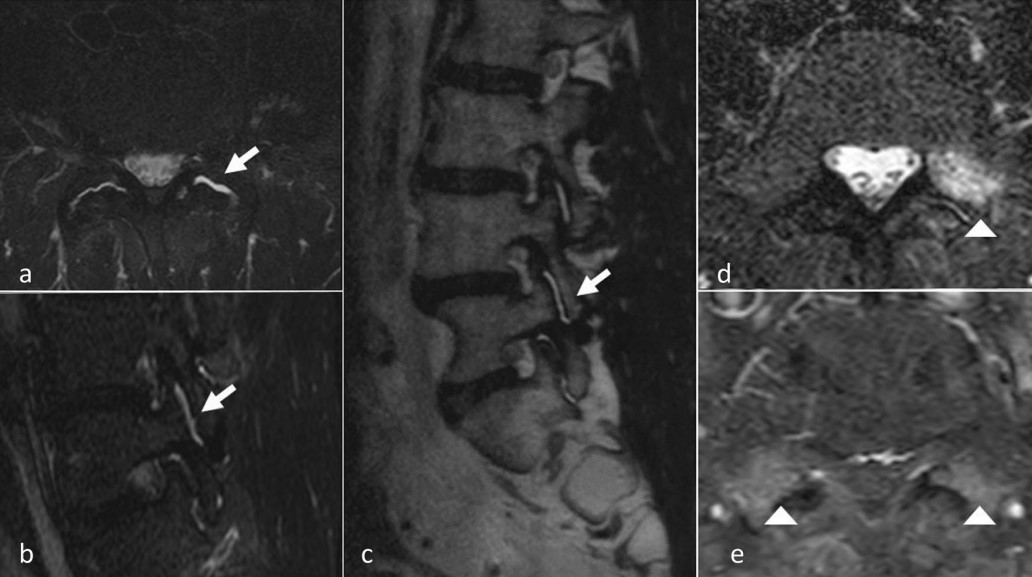

|caption=MRI imaging of facet joints. Active synovial inflammation and intra articular oedema: axial and sagittal T2 STIR views (a, b) and T2 sagittal view (c). T2 STIR and T1 gado axial views (d, e): articular process bone oedema | |||

|epidemiology=Approximately 30% of all [[Chronic Low Back Pain|chronic low back pain]] | |||

|clinicalfeatures=No reliable clinical features. Can cause [[Somatic Referred Pain|somatic referred pain]] into the lower limbs. | |||

|tests=Controlled diagnostic medial branch blocks | |||

|ddx=[[Internal Disc Disruption]], [[Sacroiliac Joint Pain]] | |||

|validity=Well validated and accepted source of pain in secondary care. | |||

|treatment=[[Lumbar Zygapophysial Joint Precision Treatment|Radiofrequency neurotomy]] | |||

}} | |||

The lumbar zygapophyseal joints are a validated source of [[Chronic Low Back Pain|chronic low back pain]]. | |||

==Anatomy== | |||

The lumbar zygapophysial joints are true synovial joints. They have hyaline cartilage that overlies the subchondral bone, a synovial membrane, a fibrous joint capsule, and a joint space (1-2mL). | The lumbar zygapophysial joints are true synovial joints. They have hyaline cartilage that overlies the subchondral bone, a synovial membrane, a fibrous joint capsule, and a joint space (1-2mL). | ||

Histological studies have shown encapsulated and free nerve endings, and the presence of substance P and calcitonin gene-related peptide. | Histological studies have shown encapsulated and free nerve endings, and the presence of substance P and calcitonin gene-related peptide. | ||

== Pathology == | ==Pathology== | ||

The causative pathology of lumbar zygapophysial joint pain is unknown.<ref name=":4">Bogduk. Low back pain In: Clinical and Radiological Anatomy of the Lumbar Spine. 5th Edition. Elsevier 2012</ref> It is thought to occur through trauma and cumulative stress over a lifetime. Possible sources are the synovial villi, capsule, and meniscal or synovial entrapments. | The causative pathology of lumbar zygapophysial joint pain is unknown.<ref name=":4">Bogduk. Low back pain In: Clinical and Radiological Anatomy of the Lumbar Spine. 5th Edition. Elsevier 2012</ref> It is thought to occur through trauma and cumulative stress over a lifetime. Possible sources are the synovial villi, capsule, and meniscal or synovial entrapments. What is clear however is that degenerative changes as detected radiographically are not associated with low back pain.<ref>Kalichman L, Li L, Kim DH, Guermazi A, Berkin V, O'Donnell CJ, Hoffmann U, Cole R, Hunter DJ. Facet joint osteoarthritis and low back pain in the community-based population. Spine (Phila Pa 1976). 2008 Nov 1;33(23):2560-5. doi: 10.1097/BRS.0b013e318184ef95. PMID: 18923337; PMCID: PMC3021980.</ref> | ||

Excessive compression or torsion can lead to microfracture and capsular avulsion of the zygapophysial joints. These post-traumatic structural changes have been shown in laboratory studies and postmortem pathoanatomic studies, but not in any antemortem studies. There are no validated techniques of identifying pathology during life<ref name=":0">Wade King and Nikolai Bogduk. Chronic Low Back Pain In: Bonica's Management of Pain. 2018</ref> | |||

It can be illustrative to compare with the cervical zygapophysial joints. In the cervical spine the joints face upwards and backwards, and therefore equally share the compressive load with the discs. Injuries are most likely to occur from weight bearing, and degenerative changes occur at all levels, most commonly at C3/4. In the lumbar spine, the zygapophysial joints face posteriorly and laterally, and share little of the axial load. The joints resist axial rotation and anterior translation. Degenerative changes arise earlier, most commonly at L4/5. | |||

It | ==History== | ||

The lumbar facet joints were first posited to be a source of low back pain in the early 20th century. It was only from the 1970s onwards where more detailed anatomical studies of the sensory supply were done. Research by Bogduk and Long in 1979, with subsequent refinements by Bogduk essentially set the stage for the modern understanding of the lumbar facet joints in [[Chronic Low Back Pain|chronic low back pain]]. | |||

{| class="wikitable" | |||

|+History of Lumbar Zygapophyseal Joint Pain as a Concept | |||

!Year | |||

!Authors | |||

!Finding | |||

|- | |||

|1911 | |||

|Joel Goldthwait | |||

|First described the lumbar facets as a potential source of pain<ref>{{Cite journal|last=GOLDTHWAIT|first=JOEL E.|date=1911-03-16|title=The Lumbo-Sacral Articulation; An Explanation of Many Cases of "Lumbago," "Sciatica" and Paraplegia|url=https://doi.org/10.1056/NEJM191103161641101|journal=The Boston Medical and Surgical Journal|volume=164|issue=11|pages=365–372|doi=10.1056/NEJM191103161641101|issn=0096-6762}}</ref> | |||

|- | |||

|1933 | |||

|Ralph Ghormely | |||

|Used the term “facet syndrome” to describe pain originating from the ZAJ. <ref>Ghormley RK. Low back pain with special reference to the articular facets, with presentation of an operative procedure. JAMA. 1933;101:773 doi: [https://doi.org/10.1001/jama.1933.02740480005002 10.1001/jama.1933.02740480005002]</ref> | |||

|- | |||

|1941 | |||

|Badgley et al | |||

|facet joint pain suggested to be the source of up to 80% of back pain.<ref>Badgley CE. The articular facets in relation to low back pain and sciatic radiation. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 1941;23:481–496. [https://journals.lww.com/jbjsjournal/Abstract/1941/23020/THE_ARTICULAR_FACETS_IN_RELATION_TO_LOW_BACK_PAIN.32.aspx Abstract]</ref> | |||

|- | |||

|1963 | |||

|Hirsch et al | |||

|Injected 11% hypertonic saline in the region of the facet joints and provoked low back and thigh pain<ref>{{Cite journal|last=Hirsch|first=Carl|last2=Ingelmark|first2=Bo-Eric|last3=Miller|first3=Malcolme|date=1963-01-01|title=The Anatomical Basis for Low Back Pain: Studies on the presence of sensory nerve endings in ligamentous, capsular and intervertebral disc structures in the human lumbar spine|url=https://doi.org/10.3109/17453676308999829|journal=Acta Orthopaedica Scandinavica|volume=33|issue=1-4|pages=1–17|doi=10.3109/17453676308999829|issn=0001-6470}}</ref> | |||

|- | |||

|1971 | |||

|Rees | |||

|Described "Multiple bilateral percutaneous rhizolysis,"<ref>Rees WES. Multiple bilateral subcutaneous rhizolysis of segmental nerves in the treatment of the intervertebral disc syndrome. Ann General Practice. 1971;16:126–127.</ref> However later shown by Bogduk that it was only a fasciotomy.<ref>{{Cite journal|last=Bogduk|first=N.|last2=Colman|first2=R. R.|last3=Winer|first3=C. E.|date=1977-03-19|title=An anatomical assessment of the "percutaneous rhizolysis" procedure|url=https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/141591|journal=The Medical Journal of Australia|volume=1|issue=12|pages=397–399|doi=10.5694/j.1326-5377.1977.tb130762.x|issn=0025-729X|pmid=141591}}</ref> | |||

|- | |||

|1971 | |||

|Shealy | |||

|Used radiofrequency neurotomy to treat ZAJ origin back pain. | |||

|- | |||

|1976 | |||

|Moony & Robertson | |||

|Intra-articular injections of hypertonic saline followed by local anaesthetic. Described non-radicular referred pain. | |||

|- | |||

|'''1979''' | |||

|'''Bogduk & Long''' | |||

|'''Detailed anatomical study of the ZAJ innervation. Developed percutaneous lumbar medial branch neurotomy.'''<ref>{{Cite journal|last=Bogduk|first=Nikolai|last2=Long|first2=Don M.|date=1979-08-01|title=The anatomy of the so-called “articular nerves” and their relationship to facet denervation in the treatment of low-back pain|url=https://thejns.org/view/journals/j-neurosurg/51/2/article-p172.xml|journal=Journal of Neurosurgery|language=en-US|volume=51|issue=2|pages=172–177|doi=10.3171/jns.1979.51.2.0172}}</ref><ref>{{Cite journal|last=Bogduk|first=N.|last2=Wilson|first2=A. S.|last3=Tynan|first3=W.|date=1982-03|title=The human lumbar dorsal rami|url=https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/7076562|journal=Journal of Anatomy|volume=134|issue=Pt 2|pages=383–397|issn=0021-8782|pmc=1167925|pmid=7076562}}</ref><ref>{{Cite journal|last=Bogduk|first=N.|date=1980-11-15|title=Lumbar dorsal ramus syndrome|url=https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/6450875|journal=The Medical Journal of Australia|volume=2|issue=10|pages=537–541|doi=10.5694/j.1326-5377.1980.tb100759.x|issn=0025-729X|pmid=6450875}}</ref><ref>{{Cite journal|last=Bogduk|first=N.|last2=Long|first2=D. M.|date=1980-03|title=Percutaneous lumbar medial branch neurotomy: a modification of facet denervation|url=https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/6446163|journal=Spine|volume=5|issue=2|pages=193–200|doi=10.1097/00007632-198003000-00015|issn=0362-2436|pmid=6446163}}</ref> '''Bogduk continued to refine the technique in the subsequent decades.''' | |||

|} | |||

==Epidemiology== | |||

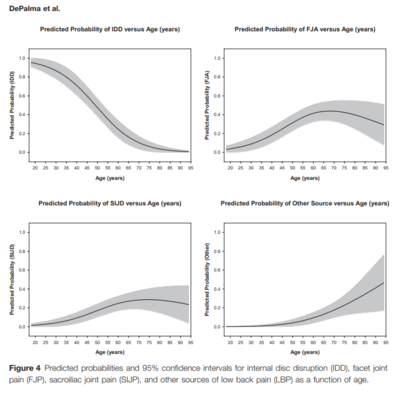

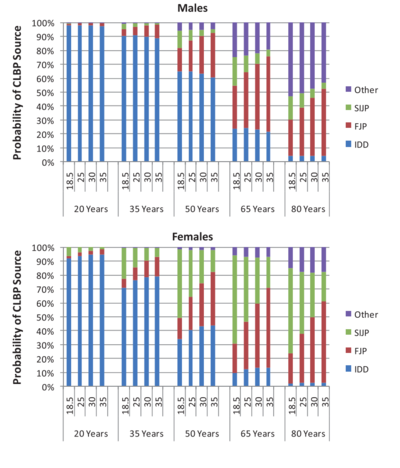

[[File:Chronic low back pain sources.PNG|thumb|'''Figure 2.''' Sources of pain in chronic low back pain as a function of age.<ref>DePalma MJ, Ketchum JM, Saullo T. What is the source of chronic low back pain and does age play a role? Pain Med. 2011 Feb;12(2):224-33. doi: 10.1111/j.1526-4637.2010.01045.x. Epub 2011 Jan 25. PMID: 21266006.</ref> <small>Copyright © 2020 American Academy of Pain Medicine</small>|400x400px]][[File:CLBP Multivariate analysis Depalma 2012.png|thumb|468x468px|'''Figure 3.''' Probability of CLBP sources by age and BMI for males and females.<ref name=":92">{{#pmid:22390231}}</ref> FJP = facet joint pain, SIJP = sacroiliac joint pain, IDD = internal disc disruption.|link=https://wikimsk.org/wiki/File:CLBP_Multivariate_analysis_Depalma_2012.png]]On the whole, studies have reported prevalence rates of around 30%.<ref>DePalma MJ. Diagnostic Nihilism Toward Low Back Pain: What Once Was Accepted, Should No Longer Be. Pain Med. 2015 Aug;16(8):1453-4. doi: 10.1111/pme.12850. Epub 2015 Jul 27. PMID: 26218010.</ref> This compares to about 40% for [[Internal Disc Disruption|disc pain]], and 20% for [[Sacroiliac Joint Pain|sacroiliac joint pain]]. | |||

In many studies, complete relief of pain was not a diagnostic criterion, but was usually 50% or 80%. As a diagnostic test, there is a balance between sensitivity and specificity depending on the cut off, with a higher relief of pain criterion resulting in a higher specificity but lower sensitivity. | |||

= | The argument of using a cut-off lower than 100% is usually around the possibility of having more than one source of pain. King and Bogduk<ref name=":0" /> reference two studies<ref>Schwarzer AC, Aprill CN, Derby R, Fortin J, Kine G, Bogduk N. The relative contributions of the disc and zygapophyseal joint in chronic low back pain. Spine (Phila Pa 1976). 1994 Apr 1;19(7):801-6. doi: 10.1097/00007632-199404000-00013. PMID: 8202798.</ref><ref name=":7">Schwarzer AC, Aprill CN, Bogduk N. The sacroiliac joint in chronic low back pain. Spine (Phila Pa 1976). 1995 Jan 1;20(1):31-7. doi: 10.1097/00007632-199501000-00007. PMID: 7709277.</ref> to argue that patients with chronic low back pain only rarely have concurrent sources of pain, and so placebo responses can't be excluded. They note that if 100% relief of pain is used then the prevalence drops to about 5% or less.<ref>Carette S, Marcoux S, Truchon R, Grondin C, Gagnon J, Allard Y, Latulippe M. A controlled trial of corticosteroid injections into facet joints for chronic low back pain. N Engl J Med. 1991 Oct 3;325(14):1002-7. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199110033251405. PMID: 1832209.</ref><ref>Jackson RP, Jacobs RR, Montesano PX. 1988 Volvo award in clinical sciences. Facet joint injection in low-back pain. A prospective statistical study. Spine (Phila Pa 1976). 1988 Sep;13(9):966-71. doi: 10.1097/00007632-198809000-00002. PMID: 2974632.</ref><ref>Laslett M, Oberg B, Aprill CN, McDonald B. Zygapophysial joint blocks in chronic low back pain: a test of Revel's model as a screening test. BMC Musculoskelet Disord. 2004 Nov 16;5:43. doi: 10.1186/1471-2474-5-43. PMID: 15546487; PMCID: PMC534802.</ref><ref>Laslett M, McDonald B, Aprill CN, Tropp H, Oberg B. Clinical predictors of screening lumbar zygapophyseal joint blocks: development of clinical prediction rules. Spine J. 2006 Jul-Aug;6(4):370-9. doi: 10.1016/j.spinee.2006.01.004. PMID: 16825041.</ref> | ||

There | They continue however that the prevalence appears to be highly dependent on age. In a study of the elderly using a 90% criteron, 34% were positive.<ref name=":8">Schwarzer AC, Wang SC, Bogduk N, McNaught PJ, Laurent R. Prevalence and clinical features of lumbar zygapophysial joint pain: a study in an Australian population with chronic low back pain. Ann Rheum Dis. 1995 Feb;54(2):100-6. doi: 10.1136/ard.54.2.100. PMID: 7702395; PMCID: PMC1005530.</ref> A later study with two publications found that the prevalence was 2% in those 20-35, 5-10% in those 35-50, 20% in those 50-65, and 30-40% in those over 65. There was also an association with age and BMI.<ref name=":93">{{#pmid:22390231}}</ref><ref name=":1">DePalma MJ, Ketchum JM, Saullo T. What is the source of chronic low back pain and does age play a role? Pain Med. 2011 Feb;12(2):224-33. doi: 10.1111/j.1526-4637.2010.01045.x. Epub 2011 Jan 25. PMID: 21266006.</ref> (figures 2 and 3) It appears that in certain groups the prevalence is as high as [[Internal Disc Disruption|internal disc disruption]]. | ||

== Clinical Features == | Importantly, there is no association with zygapophysial joint osteoarthritis.<ref name=":0" /> | ||

==Clinical Features== | |||

No reliable clinical features or imaging findings that are diagnostic | No reliable clinical features or imaging findings that are diagnostic | ||

ZJ pain can cause back pain with referral into the lower limb Some cases of chronic low back pain can be relieved by anaesthetisation of the lumbar ZJ | ZJ pain can cause back pain with referral into the lower limb. Some cases of chronic low back pain can be relieved by anaesthetisation of the lumbar ZJ | ||

*Like IDD, no clinical features that distinguish lumbar ZJ pain from other causes | *Like IDD, no clinical features that distinguish lumbar ZJ pain from other causes | ||

*Often unilateral, but can be bilateral | *Often unilateral, but can be bilateral | ||

*If pain is central, then the lumbar ZJ are unlikely to be the source.<ref>{{Cite journal|last=Schwarzer|first=A. C.|last2=Aprill|first2=C. N.|last3=Derby|first3=R.|last4=Fortin|first4=J.|last5=Kine|first5=G.|last6=Bogduk|first6=N.|date=1994-05-15|title=Clinical features of patients with pain stemming from the lumbar zygapophysial joints. Is the lumbar facet syndrome a clinical entity?|url=https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/8059268|journal=Spine|volume=19|issue=10|pages=1132–1137|doi=10.1097/00007632-199405001-00006|issn=0362-2436|pmid=8059268}}</ref> | |||

*In a study by Mooney and Robertson<ref>Mooney V, Robertson J. The facet syndrome. Clin Orthop Relat Res. 1976;115:149–156.</ref>, which demonstrated pain referral patterns of 5 normal and 15 abnormal volunteers (chronic LBP +/- sciatica) by injecting hypertonic saline: | *In a study by Mooney and Robertson<ref>Mooney V, Robertson J. The facet syndrome. Clin Orthop Relat Res. 1976;115:149–156.</ref>, which demonstrated pain referral patterns of 5 normal and 15 abnormal volunteers (chronic LBP +/- sciatica) by injecting hypertonic saline: | ||

**2 patients – pain crossed the midline | **2 patients – pain crossed the midline | ||

| Line 32: | Line 92: | ||

**In all subjects, pain abolished by lignocaine | **In all subjects, pain abolished by lignocaine | ||

== Diagnosis == | ==Diagnosis== | ||

The diagnostic criteria utilising controlled comparative diagnostic local anaesthetic blocks of the medial branches is the gold standard for diagnosis. This method has been shown to be durable over time with repeated testing at 1 year and 2 years.<ref>Pampati S, Cash KA, Manchikanti L. Accuracy of diagnostic lumbar facet joint nerve blocks: a 2-year follow-up of 152 patients diagnosed with controlled diagnostic blocks. Pain Physician. 2009 Sep-Oct;12(5):855-66. PMID: 19787011.</ref> A single block is not recommended due to the high false positive rate.<ref name=":3">Manchikanti L, Kosanovic R, Pampati V, Cash KA, Soin A, Kaye AD, Hirsch JA. Low Back Pain and Diagnostic Lumbar Facet Joint Nerve Blocks: Assessment of Prevalence, False-Positive Rates, and a Philosophical Paradigm Shift from an Acute to a Chronic Pain Model. Pain Physician. 2020 Sep;23(5):519-530. PMID: 32967394.</ref> | {{See also|Lumbar Medial Branch Blocks}} | ||

Lumbar zygapophysial joint pain cannot be diagnosed through standard clinical means, nor through plain films, CT, or MRI. It can only be diagnosed by controlled diagnostic blocks. | |||

The diagnostic criteria utilising controlled comparative diagnostic local anaesthetic blocks of the medial branches is the gold standard for diagnosis. This method has been shown to be durable over time with repeated testing at 1 year and 2 years.<ref>Pampati S, Cash KA, Manchikanti L. Accuracy of diagnostic lumbar facet joint nerve blocks: a 2-year follow-up of 152 patients diagnosed with controlled diagnostic blocks. Pain Physician. 2009 Sep-Oct;12(5):855-66. PMID: 19787011.</ref> A single block is not recommended due to the high false positive rate.<ref name=":3">Manchikanti L, Kosanovic R, Pampati V, Cash KA, Soin A, Kaye AD, Hirsch JA. Low Back Pain and Diagnostic Lumbar Facet Joint Nerve Blocks: Assessment of Prevalence, False-Positive Rates, and a Philosophical Paradigm Shift from an Acute to a Chronic Pain Model. Pain Physician. 2020 Sep;23(5):519-530. PMID: 32967394.</ref> See [[Causes and Sources of Chronic Low Back Pain#Zygapophysial Joint Pain|Causes and Sources of Chronic Low Back Pain]] for a full discussion. | |||

There are no clinical features that can distinguish between those who respond to blocks and those who don't. In fact, the presence of pain with extension or pain with extension and rotation is not correlated with positive blocks, however its ''absence'' does. See for example Revel's criteria below. | |||

{{Revel criteria}} | |||

Of note intra-articular injections are not used for the purpose of diagnosis for the following reasons:<ref>Bogduk N. Practice Guidelines for Spinal Diagnostic and Treatment Procedures, 2nd Ed. San Francisco: ISIS; 2013</ref> | |||

*They do not have diagnostic specificity. One study showed that inflammatory cytokines produced in a degenerative facet joint can leak into the epidural space.<ref>{{Cite journal|last=Igarashi|first=Akira|last2=Kikuchi|first2=Shin-ichi|last3=Konno|first3=Shin-ichi|date=2007-03|title=Correlation between inflammatory cytokines released from the lumbar facet joint tissue and symptoms in degenerative lumbar spinal disorders|url=https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/17393271|journal=Journal of Orthopaedic Science: Official Journal of the Japanese Orthopaedic Association|volume=12|issue=2|pages=154–160|doi=10.1007/s00776-006-1105-y|issn=0949-2658|pmid=17393271}}</ref> | |||

*They have no prognostic specificity for predicting the outcome of radiofrequency neurotomy. | |||

*They also don't have therapeutic utility, meaning that if it is positive there is no follow up treatment. On the other hand medial branch blocks do have therapeutic utility because if positive then radiofrequency neurotomy can be offered. | |||

==Treatment== | |||

===Precision Treatment=== | |||

{{Main|Lumbar Facet Joint Precision Treatment}} | |||

Lumbar [[Radiofrequency Neurotomy|radiofrequency ablation]] has level 2 evidence but but patients must be selected by two positive medial branch blocks with >80% pain relief. Repeated therapeutic medial branch blocks also has level 2 evidence. | |||

=== Intra-articular corticosteroid === | |||

Some practitioners use corticosteroid as a first line intervention for facet joint pain. A placebo-controlled RCT, enrolling patients with confirmed ZJ pain by way of dual medial branch blocks, showed that IA steroid did not provide any meaningful benefit above saline.<ref>{{Cite journal|last=Kennedy|first=David J|last2=Fraiser|first2=Ryan|last3=Zheng|first3=Patricia|last4=Huynh|first4=Lisa|last5=Levin|first5=Joshua|last6=Smuck|first6=Matthew|last7=Schneider|first7=Byron J|date=2018-12-12|title=Intra-articular Steroids vs Saline for Lumbar Z-Joint Pain: A Prospective, Randomized, Double-Blind Placebo-Controlled Trial|url=https://doi.org/10.1093/pm/pny225|journal=Pain Medicine|volume=20|issue=2|pages=246–251|doi=10.1093/pm/pny225|issn=1526-2375}}</ref> | |||

==Resources== | |||

{{PDF|Facet joint syndrome - Perolat 2018.pdf}} | |||

==See Also== | |||

*[[Causes and Sources of Chronic Low Back Pain]] | |||

*[[Chronic Low Back Pain]] | |||

*[[Internal Disc Disruption]] | |||

*[[Sacroiliac Joint Pain]] | |||

== References == | == References == | ||

[[Category:Lumbar Spine Conditions]] | |||

<references /> | |||

{{References}} | |||

{{Reliable sources | |||

|synonym1=lumbar facet joint pain | |||

|synonym2=facet syndrome | |||

}} | |||

Latest revision as of 09:52, 30 July 2022

| |

| Lumbar Zygapophysial Joint Pain | |

|---|---|

| Epidemiology | Approximately 30% of all chronic low back pain |

| Clinical Features | No reliable clinical features. Can cause somatic referred pain into the lower limbs. |

| Tests | Controlled diagnostic medial branch blocks |

| DDX | Internal Disc Disruption, Sacroiliac Joint Pain |

| Validity | Well validated and accepted source of pain in secondary care. |

| Treatment | Radiofrequency neurotomy |

The lumbar zygapophyseal joints are a validated source of chronic low back pain.

Anatomy

The lumbar zygapophysial joints are true synovial joints. They have hyaline cartilage that overlies the subchondral bone, a synovial membrane, a fibrous joint capsule, and a joint space (1-2mL).

Histological studies have shown encapsulated and free nerve endings, and the presence of substance P and calcitonin gene-related peptide.

Pathology

The causative pathology of lumbar zygapophysial joint pain is unknown.[1] It is thought to occur through trauma and cumulative stress over a lifetime. Possible sources are the synovial villi, capsule, and meniscal or synovial entrapments. What is clear however is that degenerative changes as detected radiographically are not associated with low back pain.[2]

Excessive compression or torsion can lead to microfracture and capsular avulsion of the zygapophysial joints. These post-traumatic structural changes have been shown in laboratory studies and postmortem pathoanatomic studies, but not in any antemortem studies. There are no validated techniques of identifying pathology during life[3]

It can be illustrative to compare with the cervical zygapophysial joints. In the cervical spine the joints face upwards and backwards, and therefore equally share the compressive load with the discs. Injuries are most likely to occur from weight bearing, and degenerative changes occur at all levels, most commonly at C3/4. In the lumbar spine, the zygapophysial joints face posteriorly and laterally, and share little of the axial load. The joints resist axial rotation and anterior translation. Degenerative changes arise earlier, most commonly at L4/5.

History

The lumbar facet joints were first posited to be a source of low back pain in the early 20th century. It was only from the 1970s onwards where more detailed anatomical studies of the sensory supply were done. Research by Bogduk and Long in 1979, with subsequent refinements by Bogduk essentially set the stage for the modern understanding of the lumbar facet joints in chronic low back pain.

| Year | Authors | Finding |

|---|---|---|

| 1911 | Joel Goldthwait | First described the lumbar facets as a potential source of pain[4] |

| 1933 | Ralph Ghormely | Used the term “facet syndrome” to describe pain originating from the ZAJ. [5] |

| 1941 | Badgley et al | facet joint pain suggested to be the source of up to 80% of back pain.[6] |

| 1963 | Hirsch et al | Injected 11% hypertonic saline in the region of the facet joints and provoked low back and thigh pain[7] |

| 1971 | Rees | Described "Multiple bilateral percutaneous rhizolysis,"[8] However later shown by Bogduk that it was only a fasciotomy.[9] |

| 1971 | Shealy | Used radiofrequency neurotomy to treat ZAJ origin back pain. |

| 1976 | Moony & Robertson | Intra-articular injections of hypertonic saline followed by local anaesthetic. Described non-radicular referred pain. |

| 1979 | Bogduk & Long | Detailed anatomical study of the ZAJ innervation. Developed percutaneous lumbar medial branch neurotomy.[10][11][12][13] Bogduk continued to refine the technique in the subsequent decades. |

Epidemiology

On the whole, studies have reported prevalence rates of around 30%.[16] This compares to about 40% for disc pain, and 20% for sacroiliac joint pain.

In many studies, complete relief of pain was not a diagnostic criterion, but was usually 50% or 80%. As a diagnostic test, there is a balance between sensitivity and specificity depending on the cut off, with a higher relief of pain criterion resulting in a higher specificity but lower sensitivity.

The argument of using a cut-off lower than 100% is usually around the possibility of having more than one source of pain. King and Bogduk[3] reference two studies[17][18] to argue that patients with chronic low back pain only rarely have concurrent sources of pain, and so placebo responses can't be excluded. They note that if 100% relief of pain is used then the prevalence drops to about 5% or less.[19][20][21][22]

They continue however that the prevalence appears to be highly dependent on age. In a study of the elderly using a 90% criteron, 34% were positive.[23] A later study with two publications found that the prevalence was 2% in those 20-35, 5-10% in those 35-50, 20% in those 50-65, and 30-40% in those over 65. There was also an association with age and BMI.[24][25] (figures 2 and 3) It appears that in certain groups the prevalence is as high as internal disc disruption.

Importantly, there is no association with zygapophysial joint osteoarthritis.[3]

Clinical Features

No reliable clinical features or imaging findings that are diagnostic

ZJ pain can cause back pain with referral into the lower limb. Some cases of chronic low back pain can be relieved by anaesthetisation of the lumbar ZJ

- Like IDD, no clinical features that distinguish lumbar ZJ pain from other causes

- Often unilateral, but can be bilateral

- If pain is central, then the lumbar ZJ are unlikely to be the source.[26]

- In a study by Mooney and Robertson[27], which demonstrated pain referral patterns of 5 normal and 15 abnormal volunteers (chronic LBP +/- sciatica) by injecting hypertonic saline:

- 2 patients – pain crossed the midline

- 3 patients – pain encompassed entire leg and foot

- Increased stimulus (i.e volume) = increased pain and increased radiation distally

- Localization of pain in the low back, buttock, and leg is a non-specific finding

- In all subjects, pain abolished by lignocaine

Diagnosis

- See also: Lumbar Medial Branch Blocks

Lumbar zygapophysial joint pain cannot be diagnosed through standard clinical means, nor through plain films, CT, or MRI. It can only be diagnosed by controlled diagnostic blocks.

The diagnostic criteria utilising controlled comparative diagnostic local anaesthetic blocks of the medial branches is the gold standard for diagnosis. This method has been shown to be durable over time with repeated testing at 1 year and 2 years.[28] A single block is not recommended due to the high false positive rate.[29] See Causes and Sources of Chronic Low Back Pain for a full discussion.

There are no clinical features that can distinguish between those who respond to blocks and those who don't. In fact, the presence of pain with extension or pain with extension and rotation is not correlated with positive blocks, however its absence does. See for example Revel's criteria below.

| Criteria | Points | Present | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Age > 65 | 1 | ||

| Pain relieved by recumbency | 1 | ||

| Absence of aggravation by coughing | 1 | ||

| Absence of aggravation by forward flexion | 1 | ||

| Absence of aggravation by rising from flexion | 1 | ||

| Absence of aggravation by hyperextension | 1 | ||

| Absence of aggravation by extension-rotation | 1 | ||

| Probability | Negative (0) | ||

5 or more criteria has a positive likelihood ratio of 3.1 for positive medial branch blocks.[30] However a follow up study found high specificity (90%) but very low sensitivity (<17%)[31]

Of note intra-articular injections are not used for the purpose of diagnosis for the following reasons:[32]

- They do not have diagnostic specificity. One study showed that inflammatory cytokines produced in a degenerative facet joint can leak into the epidural space.[33]

- They have no prognostic specificity for predicting the outcome of radiofrequency neurotomy.

- They also don't have therapeutic utility, meaning that if it is positive there is no follow up treatment. On the other hand medial branch blocks do have therapeutic utility because if positive then radiofrequency neurotomy can be offered.

Treatment

Precision Treatment

- Main article: Lumbar Facet Joint Precision Treatment

Lumbar radiofrequency ablation has level 2 evidence but but patients must be selected by two positive medial branch blocks with >80% pain relief. Repeated therapeutic medial branch blocks also has level 2 evidence.

Intra-articular corticosteroid

Some practitioners use corticosteroid as a first line intervention for facet joint pain. A placebo-controlled RCT, enrolling patients with confirmed ZJ pain by way of dual medial branch blocks, showed that IA steroid did not provide any meaningful benefit above saline.[34]

Resources

See Also

- Causes and Sources of Chronic Low Back Pain

- Chronic Low Back Pain

- Internal Disc Disruption

- Sacroiliac Joint Pain

References

- ↑ Bogduk. Low back pain In: Clinical and Radiological Anatomy of the Lumbar Spine. 5th Edition. Elsevier 2012

- ↑ Kalichman L, Li L, Kim DH, Guermazi A, Berkin V, O'Donnell CJ, Hoffmann U, Cole R, Hunter DJ. Facet joint osteoarthritis and low back pain in the community-based population. Spine (Phila Pa 1976). 2008 Nov 1;33(23):2560-5. doi: 10.1097/BRS.0b013e318184ef95. PMID: 18923337; PMCID: PMC3021980.

- ↑ 3.0 3.1 3.2 Wade King and Nikolai Bogduk. Chronic Low Back Pain In: Bonica's Management of Pain. 2018

- ↑ GOLDTHWAIT, JOEL E. (1911-03-16). "The Lumbo-Sacral Articulation; An Explanation of Many Cases of "Lumbago," "Sciatica" and Paraplegia". The Boston Medical and Surgical Journal. 164 (11): 365–372. doi:10.1056/NEJM191103161641101. ISSN 0096-6762.

- ↑ Ghormley RK. Low back pain with special reference to the articular facets, with presentation of an operative procedure. JAMA. 1933;101:773 doi: 10.1001/jama.1933.02740480005002

- ↑ Badgley CE. The articular facets in relation to low back pain and sciatic radiation. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 1941;23:481–496. Abstract

- ↑ Hirsch, Carl; Ingelmark, Bo-Eric; Miller, Malcolme (1963-01-01). "The Anatomical Basis for Low Back Pain: Studies on the presence of sensory nerve endings in ligamentous, capsular and intervertebral disc structures in the human lumbar spine". Acta Orthopaedica Scandinavica. 33 (1–4): 1–17. doi:10.3109/17453676308999829. ISSN 0001-6470.

- ↑ Rees WES. Multiple bilateral subcutaneous rhizolysis of segmental nerves in the treatment of the intervertebral disc syndrome. Ann General Practice. 1971;16:126–127.

- ↑ Bogduk, N.; Colman, R. R.; Winer, C. E. (1977-03-19). "An anatomical assessment of the "percutaneous rhizolysis" procedure". The Medical Journal of Australia. 1 (12): 397–399. doi:10.5694/j.1326-5377.1977.tb130762.x. ISSN 0025-729X. PMID 141591.

- ↑ Bogduk, Nikolai; Long, Don M. (1979-08-01). "The anatomy of the so-called "articular nerves" and their relationship to facet denervation in the treatment of low-back pain". Journal of Neurosurgery (in English). 51 (2): 172–177. doi:10.3171/jns.1979.51.2.0172.

- ↑ Bogduk, N.; Wilson, A. S.; Tynan, W. (1982-03). "The human lumbar dorsal rami". Journal of Anatomy. 134 (Pt 2): 383–397. ISSN 0021-8782. PMC 1167925. PMID 7076562. Check date values in:

|date=(help) - ↑ Bogduk, N. (1980-11-15). "Lumbar dorsal ramus syndrome". The Medical Journal of Australia. 2 (10): 537–541. doi:10.5694/j.1326-5377.1980.tb100759.x. ISSN 0025-729X. PMID 6450875.

- ↑ Bogduk, N.; Long, D. M. (1980-03). "Percutaneous lumbar medial branch neurotomy: a modification of facet denervation". Spine. 5 (2): 193–200. doi:10.1097/00007632-198003000-00015. ISSN 0362-2436. PMID 6446163. Check date values in:

|date=(help) - ↑ DePalma MJ, Ketchum JM, Saullo T. What is the source of chronic low back pain and does age play a role? Pain Med. 2011 Feb;12(2):224-33. doi: 10.1111/j.1526-4637.2010.01045.x. Epub 2011 Jan 25. PMID: 21266006.

- ↑ DePalma et al.. Multivariable analyses of the relationships between age, gender, and body mass index and the source of chronic low back pain. Pain medicine (Malden, Mass.) 2012. 13:498-506. PMID: 22390231. DOI.

- ↑ DePalma MJ. Diagnostic Nihilism Toward Low Back Pain: What Once Was Accepted, Should No Longer Be. Pain Med. 2015 Aug;16(8):1453-4. doi: 10.1111/pme.12850. Epub 2015 Jul 27. PMID: 26218010.

- ↑ Schwarzer AC, Aprill CN, Derby R, Fortin J, Kine G, Bogduk N. The relative contributions of the disc and zygapophyseal joint in chronic low back pain. Spine (Phila Pa 1976). 1994 Apr 1;19(7):801-6. doi: 10.1097/00007632-199404000-00013. PMID: 8202798.

- ↑ Schwarzer AC, Aprill CN, Bogduk N. The sacroiliac joint in chronic low back pain. Spine (Phila Pa 1976). 1995 Jan 1;20(1):31-7. doi: 10.1097/00007632-199501000-00007. PMID: 7709277.

- ↑ Carette S, Marcoux S, Truchon R, Grondin C, Gagnon J, Allard Y, Latulippe M. A controlled trial of corticosteroid injections into facet joints for chronic low back pain. N Engl J Med. 1991 Oct 3;325(14):1002-7. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199110033251405. PMID: 1832209.

- ↑ Jackson RP, Jacobs RR, Montesano PX. 1988 Volvo award in clinical sciences. Facet joint injection in low-back pain. A prospective statistical study. Spine (Phila Pa 1976). 1988 Sep;13(9):966-71. doi: 10.1097/00007632-198809000-00002. PMID: 2974632.

- ↑ Laslett M, Oberg B, Aprill CN, McDonald B. Zygapophysial joint blocks in chronic low back pain: a test of Revel's model as a screening test. BMC Musculoskelet Disord. 2004 Nov 16;5:43. doi: 10.1186/1471-2474-5-43. PMID: 15546487; PMCID: PMC534802.

- ↑ Laslett M, McDonald B, Aprill CN, Tropp H, Oberg B. Clinical predictors of screening lumbar zygapophyseal joint blocks: development of clinical prediction rules. Spine J. 2006 Jul-Aug;6(4):370-9. doi: 10.1016/j.spinee.2006.01.004. PMID: 16825041.

- ↑ Schwarzer AC, Wang SC, Bogduk N, McNaught PJ, Laurent R. Prevalence and clinical features of lumbar zygapophysial joint pain: a study in an Australian population with chronic low back pain. Ann Rheum Dis. 1995 Feb;54(2):100-6. doi: 10.1136/ard.54.2.100. PMID: 7702395; PMCID: PMC1005530.

- ↑ DePalma et al.. Multivariable analyses of the relationships between age, gender, and body mass index and the source of chronic low back pain. Pain medicine (Malden, Mass.) 2012. 13:498-506. PMID: 22390231. DOI.

- ↑ DePalma MJ, Ketchum JM, Saullo T. What is the source of chronic low back pain and does age play a role? Pain Med. 2011 Feb;12(2):224-33. doi: 10.1111/j.1526-4637.2010.01045.x. Epub 2011 Jan 25. PMID: 21266006.

- ↑ Schwarzer, A. C.; Aprill, C. N.; Derby, R.; Fortin, J.; Kine, G.; Bogduk, N. (1994-05-15). "Clinical features of patients with pain stemming from the lumbar zygapophysial joints. Is the lumbar facet syndrome a clinical entity?". Spine. 19 (10): 1132–1137. doi:10.1097/00007632-199405001-00006. ISSN 0362-2436. PMID 8059268.

- ↑ Mooney V, Robertson J. The facet syndrome. Clin Orthop Relat Res. 1976;115:149–156.

- ↑ Pampati S, Cash KA, Manchikanti L. Accuracy of diagnostic lumbar facet joint nerve blocks: a 2-year follow-up of 152 patients diagnosed with controlled diagnostic blocks. Pain Physician. 2009 Sep-Oct;12(5):855-66. PMID: 19787011.

- ↑ Manchikanti L, Kosanovic R, Pampati V, Cash KA, Soin A, Kaye AD, Hirsch JA. Low Back Pain and Diagnostic Lumbar Facet Joint Nerve Blocks: Assessment of Prevalence, False-Positive Rates, and a Philosophical Paradigm Shift from an Acute to a Chronic Pain Model. Pain Physician. 2020 Sep;23(5):519-530. PMID: 32967394.

- ↑ Revel M, Poiraudeau S, Auleley GR, Payan C, Denke A, Nguyen M, Chevrot A, Fermanian J. Capacity of the clinical picture to characterize low back pain relieved by facet joint anesthesia. Proposed criteria to identify patients with painful facet joints. Spine (Phila Pa 1976). 1998 Sep 15;23(18):1972-6; discussion 1977. doi. PMID

- ↑ Laslett M, Oberg B, Aprill CN, McDonald B. Zygapophysial joint blocks in chronic low back pain: a test of Revel's model as a screening test. BMC Musculoskelet Disord. 2004 Nov 16;5:43. doi PMID

- ↑ Bogduk N. Practice Guidelines for Spinal Diagnostic and Treatment Procedures, 2nd Ed. San Francisco: ISIS; 2013

- ↑ Igarashi, Akira; Kikuchi, Shin-ichi; Konno, Shin-ichi (2007-03). "Correlation between inflammatory cytokines released from the lumbar facet joint tissue and symptoms in degenerative lumbar spinal disorders". Journal of Orthopaedic Science: Official Journal of the Japanese Orthopaedic Association. 12 (2): 154–160. doi:10.1007/s00776-006-1105-y. ISSN 0949-2658. PMID 17393271. Check date values in:

|date=(help) - ↑ Kennedy, David J; Fraiser, Ryan; Zheng, Patricia; Huynh, Lisa; Levin, Joshua; Smuck, Matthew; Schneider, Byron J (2018-12-12). "Intra-articular Steroids vs Saline for Lumbar Z-Joint Pain: A Prospective, Randomized, Double-Blind Placebo-Controlled Trial". Pain Medicine. 20 (2): 246–251. doi:10.1093/pm/pny225. ISSN 1526-2375.

Literature Review

- Reviews from the last 7 years: review articles, free review articles, systematic reviews, meta-analyses, NCBI Bookshelf

- Articles from all years: PubMed search, Google Scholar search.

- TRIP Database: clinical publications about evidence-based medicine.

- Other Wikis: Radiopaedia, Wikipedia Search, Wikipedia I Feel Lucky, Orthobullets,