Acute Low Back Pain

Biomedically there are three aims in the approach to acute low back pain. The first is to determine whether the presenting complaint is in fact low back pain, and whether it is acute or not. The second aim is to determine whether any referred pain is somatic referred pain or radicular pain. The third aim is to identify any serious conditions.[1]

Definitions

- Main article: Low Back Pain Definitions

Topography

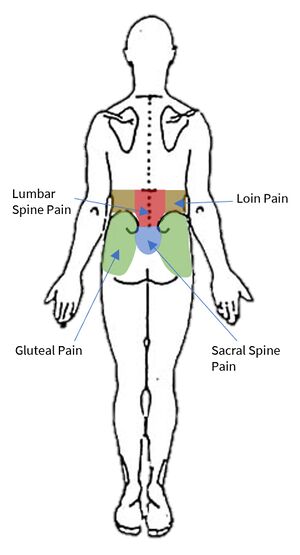

Starting with the wrong definition of low back pain can lead to the wrong diagnosis, and so it is important to be clear here. The IASP taxonomy categorises low back pain into lumbar spinal pain and sacral spinal pain. There is also an overlapping definition called lumbosacral pain. These three categories constitute the colloquial term "low back pain."

Lumbar spinal pain is pain in a region bounded superiorly by an imaginary transverse line through the tip T12, inferiorly by an imaginary transverse line through the tip of S1, and laterally by vertical lines tangential to the lateral borders of the lumbar erectores spinae.

Sacral Spinal Pain is pain in a region bounded superiorly by an imaginary transverse line through the tip of S1, inferiorly by an imaginary transverse line through the posterior sacrococcygeal joints, and laterally by imaginary lines passing through the posterior superior and posterior inferior iliac spines."

Lumbosacral Pain is pain perceived as arising from a region encompassing or centred over the lower third of the lumbar region as described above and the upper third of the sacral region as described above.

Acuity

Acute pain is pain that has been present for no longer than 12 weeks. Subacute pain is pain present for longer than 5 or 7 weeks but less than 12 weeks. The management differs depending on the acuity.

Referred Pain

- Main article: Low_Back_Pain_Definitions#Referred_Pain

Referred pain is "pain perceived as arising or occurring in a region of the body innervated by nerves or branches of nerves other than those that innervate the actual source of pain"

Visceral referred pain is referred pain where the source lies in an organ or blood vessel of the body. With low back pain, the uterus and abdominal aorta are important considerations. Other viscera with higher segmental supply may cause back pain such as pancreatitis, but this may be due to irritation of the posterior abdominal wall, in which case the pain is not truly referred in nature.

Somatic referred pain is referred pain where the source originates in a tissue or structure of the body wall or limbs. A number of structures in the lumbar spine are capable of nociception including the lumbar zygapophysial joints, intervertebral discs, sacroiliac joints, and more.

Radicular pain is a subset of neuropathic pain, and refers to pain that is evoked with stimulation of the nerve roots or dorsal root ganglion of a spinal nerve. In radicular pain, the pain is felt in the peripheral innervation of the affected nerve.

Aetiology

Unlike with chronic low back pain there is little research on the aetiology of acute low back pain. No patho-anatomic diagnosis of low back pain can be made clinically without the use of special investigations (e.g. discography, medial branch blocks, sacroiliac joint blocks). Special investigations are not appropriate for acute low back pain, and are reserved for chronic low back pain. Furthermore medical imaging is not able to identify sources of pain other than fractures.

The most important part of the assessment in acute low back pain is evaluating for red flag conditions. Fractures occur between 1-4% of cases, malignancy in 0.2%, and infection in 0.01%. Other conditions that are important to detect are cauda equina, and spondyloarthropathies.[1]

In the acute setting in the absence of red flags, the diagnosis is simply "acute low back pain."[2]

Prognosis

- Main article: Prognosis of Low Back Pain

It is sometimes stated in guidelines that most patients with acute low back pain make an excellent recovery. The evidence is in fact quite conflicting, with markedly different findings across different studies. Overall the treating doctor can relay optimism, but be guarded about prognosis. The data on recurrence rates are also conflicting.

A systematic review of 11 studies performed in the US, Australia and Europe on patients with non-specific back pain found that recovery occurred in 33% of patients at 3 months, and by 1 year 65% still had pain. In studies that used total absence of pain as a criterion, 71% still had pain at 12 months. In studies that had a less stringent criteria, 57% still had pain at 12 months.[3]

Prognostic risk factors are broadly categorised into biological and psychosocial. Predictors of recurrence are often variable across studies, but generally include [4][5]

- Sociodemographic: female gender, obesity, poor educational level

- Current History: previous episodes, duration of episode, days to seek care, pain and disability levels, leg pain

- General Health: Smoking, habitual physical activity, perceived health, use of medications

- Psychosocial: Perceived risk of recurrence, depression, anxiety, fear-avoidance behaviour, overprotective family or lack of support.

- Work-related: Involvement in heavy lifting or awkward positions, job satisfaction, compensable case

- Others: MRI findings, qualification of practitioner.

The psychosocial and occupational barriers are termed "yellow flags".

Assessment and Management Algorithm

Because a specific tissue diagnosis cannot be made with any validity in the vast majority of cases of acute low back pain, the management is not based on finding and treating a particular cause.

The Musculoskeletal algorithm starts with Triage which refers to confirming the taxonomy and looking for serious causes of pain. After Management is Concern which refers to seeing if the patient is responding. Vigilance is rechecking for red flag conditions at subsequent encounters. Reinforce is reinforcing previous interventions, and Supplement is applying adjunct measures.

Assessment

Triage begins with checking that the patient does have back pain and that it is likely to be a benign condition arising from the spine, rather than another serious cause. Red flags have poor predictive value, but this is not their value, they are simply an alerting feature. It lets the doctor know to consider exploring the possibility of serious conditions further.

History

A pain history should be undertaken. Some advocate the traditional systematic approach[6] but this has not been proven to improve diagnostic accuracy and many of the questions have unproven or non-existent validity. This approach is also usually not viable in primary care, and the doctor will make a judgement as to the most pertinent questions to ask while carefully safety netting.

The traditional systematic approach includes questioning around presenting complaint, length of illness, site, location and extent of spread, quality, severity, frequency, duration, time of onset, mode of onset, precipitating factors, aggravating factors, relieving factors, and associated fevers.

The presenting complaint and site are around confirming that they do indeed have back pain as opposed to loin pain or gluteal pain for example. The length of illness is around establishing if it is acute or chronic.

The location and extent of spread and quality are about distinguishing somatic referred from radicular pain. Incorrectly distinguishing radicular pain from somatic referred pain is a common pitfall in diagnosis and with incorrect diagnosis this frequently leads to incorrect treatment.

The patient should be asked where their "main" or "worst" pain is, or where they feel the pain most often and most consistently. Reciprocally they can be asked where they feel the pain only sometimes.

Patients may have a combination of somatic and referred pain from the same process e.g. a herniated disc causing somatic pain from irritation of the dura of the nerve root plus radicular pain from irritation of the nerve root itself.

| Somatic Referred | Radicular | |

|---|---|---|

| Pain quality | Dull, deep ache, or pressure-like, perhaps like an expanding pressure | Shooting, lancinating, or electric-shocks |

| Relation to back pain | Referred pain is always concurrent with back pain. If the back pain ceases then so does the referred pain. If the back pain flares then so does the leg pain intensity and spatial spread. | Not always concurrent with back pain. |

| Distribution | Anywhere in the lower limb, fixed in location, commonly in the buttock or proximal thigh. Spread of pain distal to the knee can occur when severe even to the foot, and it can skip regions such as the thigh. It can feel like an expanding pressure into the lower limb, but remains in location once established without traveling. It can wax and wane, but does so in the same location. | Entire length of lower limb, but below knee > above knee. In mild cases the pain may be restricted proximally. |

| Pattern | Felt in a wide area, with difficult to perceive boundaries, often demonstrated with an open hand rather than pointing finger. The centres in contrast can be confidently indicated. | Travels along a narrow band no more than 5-8 cm wide in a quasi-segmental fashion but not related to dermatomes (dynatomal). |

| Depth | Deep only, lacks any cutaneous quality | Deep as well as superficial |

| Neurological signs | Not characteristic | Favours radicular pain, but not required. |

| Neuroanatomical basis | Discharge of the peripheral nerve endings of Aδ and C fibres from the lower back converge onto second order neurons in the dorsal horn that also receive input from from the lower limb, and so the frontal lobe has no way of knowing where the pain came from. | Heterotopic discharge of Aδ, Aβ, and C fibres through stimulation of a dorsal root or dorsal root ganglion of a spinal nerve, typically in the presence of inflammation, with pain being felt in the peripheral innervation of the affected nerve |

The severity of back pain does not correlate with the severity of the disease process but can be recorded as a baseline VAS. The frequency and duration relates to how it waxes and wanes and how long for, and is usually related to aggravating factors rather than the disease process. They are not of diagnostic value.

The time of onset is about whether they have morning stiffness. The sensitivity is moderate but specificity is poor for spondyloarthropathies. The mode of onset is how it started such as spontaneously or with an injury. Spontaneous pain with an explosive onset is anecdotally concerning.

Precipitating factors are activities that bring on pain and aren't helpful diagnostically. Aggravating factors are activities that aggravate the pain, and the absence of any mechanical aggravating factors is of concern. Relieving factors are those that improve the pain such as medications, wheat bags, etc. Pain that isn't relieved by rest may raise concern for a serious disorder.

Associated features may be the most helpful category of enquiry in terms of identifying serious causes, and is discussed in the red flags section below.

Red Flags

A red flag checklist can be used. There are case reports of red flag conditions being missed, and that they may have been identified earlier if the correct questions were asked.

- History of: Trauma, sports injury, fever, night sweats, recent surgery, catheterisation, venipuncture, illicit drug use, weight loss, cancer, occupational exposure, hobby exposure, overseas travel, pain severe worsening or unremitting especially at night

- Cardiovascular: Risk factors

- Respiratory: Cough in a smoker or ex-smoker

- Gentio-urinary: Infection, haematuria, retention, stream problems

- Gynaecological: abnormal uterine bleeding, dysmenorrhoea

- Haematological

- Endocrine: Diabetes, corticosteroids, parathyroid

- Musculoskeletal: pain elsewhere

- Neurologic: symptoms/signs including for cauda equina compression

- Skin: Infection, rashes

- Gastrointestinal: Diarrhoea, inflammatory bowel disease

- Demographic: Aged over 50 years with first episode, especially age over 65 years

The most important alerting features are a past history of cancer, age greater than 50, prolonged illness, failure to improve with treatment, and unexplained weight loss.

For fracture, the most important risk factors are trauma, prolonged use of corticosteroids, especially in the elderly. In sports people pars interarticularis fractures should be considered.

For infection, symptoms are often subtle, but may include malaise and fever. The risk factors are mainly those that make the individual susceptible such as penetrating injuries, or underlying conditions. Exotic infections are more likely with occupational exposure, certain hobbies, or recent travel.

For malignancy symptoms again may be subtle. Cough in a smoker or ex-smoker is a concern for spinal metastases. Myeloma may not be evident on history.

A history of psoriasis and inflammatory bowel disease are clues for spondyloarthropathy. Pain elsewhere is also a clue for a systemic rheumatology conditions.

Hyperparathyroidism and Paget's disease are occult causes of spinal pain. There are usually no clues on history.

Cardiovascular risk factors alert for possible aortic aneurysm.

Neurological features should be assessed along with any spinal pain, along with symptoms of cauda equina compression.

History of a urinary tract infection, haematuria, and urinary retention should lead to assessment of the renal tract.

Investigations

If a red flag condition is suspected then appropriate investigations should be done. Such investigations are not recommended as part of the routine assessment of low back pain, as they are not designed to investigate the cause of back pain. They also aren't screening tests in the absence of concern.

| Category | Risk Factors | Specific conditions | Investigations |

|---|---|---|---|

| Simple low back pain | No risk factors | N/A | Nil. Reassess after 4 to 6 weeks if no improvement |

| Primary tumours (rare, 0.04% of all tumours) | myeloma | Myeloma screen | |

| bone and cartilage tumours | Imaging | ||

| Secondary tumours | History of cancer, clinical suspicion | Prostate | Calcium, ALP, PSA, ESR and/or CRP, imaging |

| Breast, lung, thyroid, kidney, gastrointestinal, melanoma | Plain radiography, ESR and/or CRP. If radiograph normal but elevated markers then MRI. | ||

| Infection | fever, immunosupression, dialysis, IVDU, invasive procedure | Osteomyelitis, epidural abscess | MRI if moderate to high risk. ESR and/or CRP if low risk, with MRI if elevated. |

| Fracture | Elderly, prolonged corticosteroid use, significant trauma, mild trauma with history or risk factors for osteoporosis. | Vertebral compression fracture | Plain radiograph |

| Spondyloarthropathy | Ankylosing spondylitis | ESR and/or CRP | |

| Metabolic bone disease | Paget's disease, Hyperparathyroidism | Calcium | |

| Visceral disease | Aortic aneurysm | Abdominal exam, ultrasound (e.g. bedside) | |

| Retroperitoneal disease | Abdominal exam, ultrasound (e.g. bedside) | ||

| Pelvic disease | Pelvic examination, rectal examination | ||

| Modified from Bogduk et al. Management of Acute and Chronic Low Back Pain. Elsevier 2002. | |||

References

- ↑ 1.0 1.1 Wade King and Nikolai Bogduk. Acute Low Back Pain. Bonica's Management of Pain. 2018

- ↑ Bogduk et al. Medical Management of Acute and Chronic Low Back Pain. Chapter 3. Elsevier 2002.

- ↑ Itz CJ, Geurts JW, van Kleef M, Nelemans P. Clinical Course of Non-Specific Low Back Pain: A Systematic Review of Prospective Cohort Studies Set in Primary Care. Eur J Pain. 2013;17(1):5-15. doi: 10.1002/j.1532-2149.2012.00170.x.

- ↑ Machado GC, et al. Can Recurrence After an Acute Episode of Low Back Pain Be Predicted? Phys Ther. 2017 Sep 1;97(9):889-895. doi: 10.1093/ptj/pzx067. PMID: 28969347

- ↑ National Health Committee. Low Back Pain: A Pathway to Prioritisation. 2015. Full Text

- ↑ Bogduk et al. Management of Acute and Chronic Low Back Pain. Chapter 5. Elsevier 2002

- ↑ Bogduk et al. Medical Management of Acute and Chronic Low Back Pain: An Evidence Based Approach. Elsevier Science. 2002