Acute Low Back Pain

Biomedically there are three aims in the approach to acute low back pain. The first is to determine whether the presenting complaint is in fact low back pain, and whether it is acute or not. The second aim is to determine whether any referred pain is somatic referred pain or radicular pain. The third aim is to identify any serious conditions.[1]

Definitions

- Main article: Low Back Pain Definitions

Topography

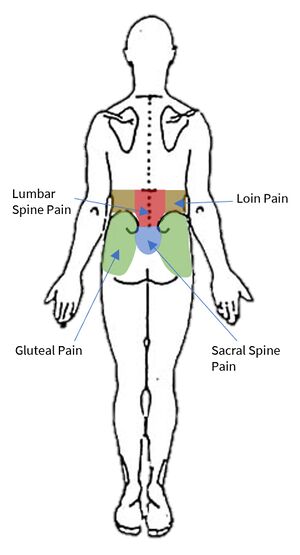

Starting with the wrong definition of low back pain can lead to the wrong diagnosis, and so it is important to be clear here. The IASP taxonomy categorises low back pain into lumbar spinal pain and sacral spinal pain. There is also an overlapping definition called lumbosacral pain. These three categories constitute the colloquial term "low back pain."

Lumbar spinal pain is pain in a region bounded superiorly by an imaginary transverse line through the tip T12, inferiorly by an imaginary transverse line through the tip of S1, and laterally by vertical lines tangential to the lateral borders of the lumbar erectores spinae.

Sacral Spinal Pain is pain in a region bounded superiorly by an imaginary transverse line through the tip of S1, inferiorly by an imaginary transverse line through the posterior sacrococcygeal joints, and laterally by imaginary lines passing through the posterior superior and posterior inferior iliac spines."

Lumbosacral Pain is pain perceived as arising from a region encompassing or centred over the lower third of the lumbar region as described above and the upper third of the sacral region as described above.

Acuity

Acute pain is pain that has been present for no longer than 12 weeks. Subacute pain is pain present for longer than 5 or 7 weeks but less than 12 weeks. The management differs depending on the acuity.

Referred Pain

- Main article: Low_Back_Pain_Definitions#Referred_Pain

Referred pain is "pain perceived as arising or occurring in a region of the body innervated by nerves or branches of nerves other than those that innervate the actual source of pain"

Visceral referred pain is referred pain where the source lies in an organ or blood vessel of the body. With low back pain, the uterus and abdominal aorta are important considerations. Other viscera with higher segmental supply may cause back pain such as pancreatitis, but this may be due to irritation of the posterior abdominal wall, in which case the pain is not truly referred in nature.

Somatic referred pain is referred pain where the source originates in a tissue or structure of the body wall or limbs. A number of structures in the lumbar spine are capable of nociception including the lumbar zygapophysial joints, intervertebral discs, sacroiliac joints, and more.

Radicular pain is a subset of neuropathic pain, and refers to pain that is evoked with stimulation of the nerve roots or dorsal root ganglion of a spinal nerve. In radicular pain, the pain is felt in the peripheral innervation of the affected nerve.

Aetiology

Unlike with chronic low back pain there is little research on the aetiology of acute low back pain. No patho-anatomic diagnosis of low back pain can be made clinically without the use of special investigations (e.g. discography, medial branch blocks, sacroiliac joint blocks). Special investigations are not appropriate for acute low back pain, and are reserved for chronic low back pain. Furthermore medical imaging is not able to identify sources of pain other than fractures.

The most important part of the assessment in acute low back pain is evaluating for red flag conditions. Fractures occur between 1-4% of cases, malignancy in 0.2%, and infection in 0.01%. Other conditions that are important to detect are cauda equina, and spondyloarthropathies.[1]

In the acute setting in the absence of red flags, the diagnosis is simply "acute low back pain."[2]

Prognosis

- Main article: Prognosis of Low Back Pain

It is sometimes stated in guidelines that most patients with acute low back pain make an excellent recovery. The evidence is in fact quite conflicting, with markedly different findings across different studies. Overall the treating doctor can relay optimism, but be guarded about prognosis. The data on recurrence rates are also conflicting.

A systematic review of 11 studies performed in the US, Australia and Europe on patients with non-specific back pain found that recovery occurred in 33% of patients at 3 months, and by 1 year 65% still had pain. In studies that used total absence of pain as a criterion, 71% still had pain at 12 months. In studies that had a less stringent criteria, 57% still had pain at 12 months.[3]

Prognostic risk factors are broadly categorised into biological and psychosocial. Predictors of recurrence are often variable across studies, but generally include [4][5]

- Sociodemographic: female gender, obesity, poor educational level

- Current History: previous episodes, duration of episode, days to seek care, pain and disability levels, leg pain

- General Health: Smoking, habitual physical activity, perceived health, use of medications

- Psychosocial: Perceived risk of recurrence, depression, anxiety, fear-avoidance behaviour, overprotective family or lack of support.

- Work-related: Involvement in heavy lifting or awkward positions, job satisfaction, compensable case

- Others: MRI findings, qualification of practitioner.

The psychosocial and occupational barriers are termed "yellow flags".

Assessment and Management Algorithm

Because a specific tissue diagnosis cannot be made with any validity in the vast majority of cases of acute low back pain, the management is not based on finding and treating a particular cause.

The Musculoskeletal algorithm starts with Triage which refers to confirming the taxonomy and looking for serious causes of pain. After Management is Concern which refers to seeing if the patient is responding. Vigilance is rechecking for red flag conditions at subsequent encounters. Reinforce is reinforcing previous interventions, and Supplement is applying adjunct measures.

Assessment

Triage begins with checking that the patient does have back pain and that it is likely to be a benign condition arising from the spine, rather than another serious cause. Red flags have poor predictive value, but this is not their value, they are simply an alerting feature. It lets the doctor know to consider exploring the possibility of serious conditions further.

Pain History

A pain history should be undertaken. Some advocate the traditional systematic approach[6] but this has not been proven to improve diagnostic accuracy and many of the questions have unproven or non-existent validity. This approach is also usually not viable in primary care, and the doctor will make a judgement as to the most pertinent questions to ask while carefully safety netting.

The traditional systematic approach includes questioning around presenting complaint, length of illness, site, location and extent of spread, quality, severity, frequency, duration, time of onset, mode of onset, precipitating factors, aggravating factors, relieving factors, and associated fevers.

The presenting complaint and site are around confirming that they do indeed have back pain as opposed to loin pain or gluteal pain for example. The length of illness is around establishing if it is acute or chronic.

The location and extent of spread and quality are about distinguishing somatic referred from radicular pain. Incorrectly distinguishing radicular pain from somatic referred pain is a common pitfall in diagnosis and with incorrect diagnosis this frequently leads to incorrect treatment.

The patient should be asked where their "main" or "worst" pain is, or where they feel the pain most often and most consistently. Reciprocally they can be asked where they feel the pain only sometimes.

Patients may have a combination of somatic and referred pain from the same process e.g. a herniated disc causing somatic pain from irritation of the dura of the nerve root plus radicular pain from irritation of the nerve root itself.

| Somatic Referred | Radicular | |

|---|---|---|

| Pain quality | Dull, deep ache, or pressure-like, perhaps like an expanding pressure | Shooting, lancinating, or electric-shocks |

| Relation to back pain | Referred pain is always concurrent with back pain. If the back pain ceases then so does the referred pain. If the back pain flares then so does the leg pain intensity and spatial spread. | Not always concurrent with back pain. |

| Distribution | Anywhere in the lower limb, fixed in location, commonly in the buttock or proximal thigh. Spread of pain distal to the knee can occur when severe even to the foot, and it can skip regions such as the thigh. It can feel like an expanding pressure into the lower limb, but remains in location once established without traveling. It can wax and wane, but does so in the same location. | Entire length of lower limb, but below knee > above knee. In mild cases the pain may be restricted proximally. |

| Pattern | Felt in a wide area, with difficult to perceive boundaries, often demonstrated with an open hand rather than pointing finger. The centres in contrast can be confidently indicated. | Travels along a narrow band no more than 5-8 cm wide in a quasi-segmental fashion but not related to dermatomes (dynatomal). |

| Depth | Deep only, lacks any cutaneous quality | Deep as well as superficial |

| Neurological signs | Not characteristic | Favours radicular pain, but not required. |

| Neuroanatomical basis | Discharge of the peripheral nerve endings of Aδ and C fibres from the lower back converge onto second order neurons in the dorsal horn that also receive input from from the lower limb, and so the frontal lobe has no way of knowing where the pain came from. | Heterotopic discharge of Aδ, Aβ, and C fibres through stimulation of a dorsal root or dorsal root ganglion of a spinal nerve, typically in the presence of inflammation, with pain being felt in the peripheral innervation of the affected nerve |

The severity of back pain does not correlate with the severity of the disease process but can be recorded as a baseline VAS. The frequency and duration relates to how it waxes and wanes and how long for, and is usually related to aggravating factors rather than the disease process. They are not of diagnostic value. The time of onset is about whether they have morning stiffness. The sensitivity is moderate but specificity is poor for spondyloarthropathies.

The mode of onset is how it started such as spontaneously or with an injury. Spontaneous pain with an explosive onset is anecdotally concerning. Otherwise the circumstances of onset are not usually helpful in a diagnostic or prognostic sense. Possibly twisting injuries may be a risk for torsion injuries, but a patho-anatomical prediction can't be made. Likewise sudden axial loading may be a risk for a compression injury. Extension injuries in sportspeople may be the exception for relevance as this indicate a pars interarticularis fracture.

Precipitating factors are activities that bring on pain and aren't helpful diagnostically. Aggravating factors are activities that aggravate the pain, and the absence of any mechanical aggravating factors is of concern. Relieving factors are those that improve the pain such as medications, wheat bags, etc. Pain that isn't relieved by rest may raise concern for a serious disorder.

Associated features may be the most helpful category of enquiry in terms of identifying serious causes, and is discussed as part of the red flags section below.

Red Flags

Red flag conditions are rare, and so the pre-test probability is in favour of the pain being benign. Red flag conditions are suspected primarily based on the history and examination. Identifying certain conditions makes no difference to the outcome, while in other cases it does.

A red flag checklist can be used. There are case reports of red flag conditions being missed, and that they may have been identified earlier if the correct questions were asked. Red flags should be checked for at each visit (i.e. vigilance).

- History of: Trauma, sports injury, fever, night sweats, recent surgery, catheterisation, venipuncture, illicit drug use, weight loss, cancer, occupational exposure, hobby exposure, overseas travel, pain severe worsening or unremitting especially at night

- Cardiovascular: Risk factors

- Respiratory: Cough in a smoker or ex-smoker

- Gentio-urinary: Infection, haematuria, retention, stream problems

- Gynaecological: abnormal uterine bleeding, dysmenorrhoea

- Haematological

- Endocrine: Diabetes, corticosteroids, parathyroid

- Musculoskeletal: pain elsewhere

- Neurologic: symptoms/signs including for cauda equina compression

- Skin: Infection, rashes

- Gastrointestinal: Diarrhoea, inflammatory bowel disease

- Demographic: Aged over 50 years with first episode, especially age over 65 years

Cancer:, the pre-test probability is low at less than 0.7%. Most patients who have cancer as a cause are elderly. The single strongest predictor is a past history of cancer. Other indicators of malignancy are lack of relief with bed rest, unexplained weight loss, failure to improve with therapy, and prolonged pain. Cough in a smoker or ex-smoker is a concern for spinal metastases. Myeloma may not be evident on history. Negative predictors are age less than 50, no past history of cancer, no weight loss, and no failure to improve with therapy. With a combination of the above, cancer is extremely unlikely.

Fracture:, major trauma is a risk. Minor trauma is only a risk if it is associated with osteoporosis, older age (>50), and/or history of prolonged corticosteroid use. In sports people pars interarticularis fractures should be considered.

Infection:, symptoms are often subtle, but may include malaise and fever. The risk factors are mainly those that make the individual susceptible such as penetrating injuries, or underlying conditions. Exotic infections are more likely with occupational exposure, certain hobbies, or recent travel.

Spondyloarthropathy: The earliest signs are morning stiffness, slow onset at age less than 30, and improvement with exercise. A history of psoriasis and inflammatory bowel disease are also clues. A combination of 4 out of 5 of morning stiffness, improvement with exercise, onset under 40, slow onset, and duration > 3 months has a +LR of 6.3, and -LR of 17. Generally ankylosing spondylitis is impossible to diagnosis early in the evolution and plain films do not generally detect changes in early disease. Note, pain elsewhere is also a clue for a systemic rheumatology conditions.

Other: Hyperparathyroidism and Paget's disease are occult causes of spinal pain. There are usually no clues on history.

Cardiovascular risk factors alert for possible aortic aneurysm.

Neurological features should be assessed along with any spinal pain, along with symptoms of cauda equina compression.

History of a urinary tract infection, haematuria, and urinary retention should lead to assessment of the renal tract.

Psychosocial Assessment

The aim of the psychological and social history is to identify so called "yellow flags." Psychosocial factors correlate only weakly with pain, but correlate strongly with disability. Psychological factors account for 30% of the variance between patients that become chronic pain sufferers and those who don't. The factors accounting for the remaining variance is undetermined, as biomedical factors don't account for the remaining variance either.[8]

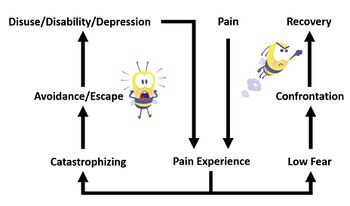

One important psychological feature amongst yellow flags is fear-avoidance behaviour. Fearful patients are scared of underlying serious conditions, scared of making it worse, scared of the prognosis, and therefore avoid movement and activity. This is an unhelpful cognitive pattern that leads to worsening disability. Fears should be managed if identified as they can negatively impact their rehabilitation.

Catastrophising is another poor prognostic psychological feature that is defined as "an exaggerated negative mental set brought to bear during actual or anticipated pain experience." It is associated with greater distress, lower mood, greater disability, and a worse prognosis. Anxiety and depression are other important negative prognostic factors

It is thought that yellow flags should be identified early in the patients course of low back pain. They are yellow not red because they don't need as urgent recognition. Patients and generally stratified according to their risk of poor outcome in order to provide targeted care. There is no consistent strong evidence that identifying and intervening on psychosocial risk factors early, however it has "conceptual validity," low cost, and so it is recommended to do so.

The STarT Back study (Subgroups for Targeted Treatment) showed that that early detection of psychosocial factors can improve outcomes. It has been validated as a predictive tool, and has also been evaluated in an RCT which showed overall higher adjusted mean changes in Roland Morris Disability Questionnaire scores in the intervention group compared to the control usual care group at 4 months (4.7 vs 3.0, effect size 0.32), and at 12 months (4.3 vs 3.3, effect size 0.19)[9][10]

STarT Back is a stratified care approach developed in the UK has been shown to improve outcomes including quicker return to work. The findings haven't been reproduced in other health systems like New Zealand. A trial using an adapted STarT Back approach in the United States did not show an improvement in patient outcomes.[11]

STarT have an online training module. The approach includes a nine-item questionnaire that assesses primarily for psychosocial risk factors such as fear avoidance and catastrophising. The original 9-item tool is able to predict persistent disabling and bothersome low back pain at 6 months with a sensitivity of 85%, specificity of 81%, and positive likelihood ratio of 4.5. A modified 6-item tool has a sensitivity of 89%, and specificity of 84%, and positive likelihood ratio of 5.5.

| Disagree

0 |

Agree 1 | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | My back pain has spread down my leg(s) at some time in the last 2 weeks | ☐ | ☐ |

| (2) | I have had pain in the shoulder or neck at some time in the last 2 weeks | ☐ | ☐ |

| 3 | I have only walked short distances because of my back pain | ☐ | ☐ |

| 4 | In the last 2 weeks, I have dressed more slowly than usual because of back pain | ☐ | ☐ |

| (5) | It’s not really safe for a person with a condition like mine to be physically active | ☐ | ☐ |

| (6) | Worrying thoughts have been going through my mind a lot of the time | ☐ | ☐ |

| 7 | I feel that my back pain is terrible and it’s never going to get any better | ☐ | ☐ |

| 8 | In general I have not enjoyed all the things I used to enjoy | ☐ | ☐ |

| 9 | Overall, how bothersome has your back pain been in the last 2 weeks? | ☐ | ☐ |

| ☐ Not at all (0) ☐ slightly (0) ☐ moderately (0) ☐ very much (1) ☐ extremely (1) | |||

| Scoring 9-item questionnaire | |||

| Total score (all 9):_____________________ Sub Score (Q5-9):_____________________

Total score 3 or less = Low risk Total score 4 or more -> sub score Q5-9 is 3 or less = medium risk sub score Q5-9 is 4 or more = high risk | |||

| Scoring 6-item questionnaire (Q2, 5, and 6 removed) | |||

| Total score (all 6):_____________________

Total score 2 or less = Low risk Total score 3 or more = not at low risk | |||

With the original 9-item questionnaire, the patient is classified as having low, medium, or high risk of poor outcome according to the score in the questionnaire.

- Low risk patients are given advice, reassurance, education, pain medication if required, their concerns are addressed, and they are booked for a review if necessary.

- Medium risk patients receive the same key messages and a short course of routine physiotherapy (or osteopathy or chiropractic) with clear functionally based treatment goals. Deterioration results in referral back to the GP, and if they don't respond after four weeks or don't meet their goals after three months then they are referred for specialist opinion or pain services.

- High risk patients receive the same key messages, conventional physiotherapy if indicated, plus psychologically informed physiotherapy. Psychologically informed physiotherapy includes CBT, addressing unhelpful beliefs, promoting self-management, building confidence and self-efficacy, grading and pacing, physical activity, and facilitating return to usual activities.

The FREE study was a pragmatic cluster-randomised controlled trial in General Practices in New Zealand. Eight general practices were randomly assigned to intervention practices (34 GPs in 4 practices), and control practices (29 GPs) in 3 practices. The Intervention GPs were trained in the FREE approach which prioritises early identification and management of barriers to recovery. 88% of patients had pain of less than 6 weeks duration. At 6 months there was no difference in the primary outcome of adjusted mean RMDQ.[12]

The full list of typical yellow flags is shown below.

| Work | Behaviours |

|---|---|

| Belief that all pain must be abolished before attempting to return to work or normal activity | Passive attitude to rehabilitation |

| Expecting increased pain with activity or work | Use of extended rest |

| Belief that work is harmful | Reduced activity with significant withdrawal from activities of daily living |

| Poor work history | Avoidance of normal activity |

| Unsupportive work environment | Increased alcohol consumption or other unhelpful substances since pain onset |

| Beliefs | Affective |

| Belief that pain is harmful, resulting in fear-avoidance behaviour | Depression |

| Catastrophising | Feeling useless and not needed |

| Misinterpreting bodily symptoms | Irritability |

| Belief that pain is uncontrollable | Anxiety about heightened bodily sensations |

| Poor compliance with exercise | Reduced interest in socialising |

| Expectation of a passive "heroic" medical intervention that will completely cure their pain | Over-protective or conversely socially punitive partner |

| Low educational background | Lack of social support |

Physical Examination

- Main article: Lumbar Spine Examination

The physical examination of the lumbar spine in general lacks reliability and validity. In short, it does not provide a diagnosis of acute low back pain. However, there are three main reason for doing a physical examination.[13]

- The first reason is that patients expect it, and doing it shows interest and caring.

- The second reason is that if no signs of somatic dysfunction are found in the spine, then this could indicate a serious underlying visceral or vascular condition. However, due to visceral referred pain, patients with visceral pathology can still have somatic segmental dysfunction. Therefore an abdominal and vascular examination is still warranted in those at increased risk.

- The third reason is that the doctor can provide positive reinforcement (e.g. celebrating normal findings) with the view of reducing patient fear.

The lumbar spine exam involvs inspection, palpation, and movement testing.

- Inspection: posture standing and sitting (scoliosis, kyphosis, loss of lordosis), dynamic posture (antalgic gait), deformities, scars, puncture marks, swelling. The reliability reported in studies has varied. The validity is unknown.

- Palpation: altered sensitivity (hypoesthesia, hyperesthesia), tenderness and its relationship to bony landmarks, and whether localised or diffuse. The reliability is excellent for tenderness somewhere in the lumbar spine (kappa 1.0)[14], but when the location is specified the agreement is variable. Tenderness over the iliac crest superomedial to the PSIS is good (kappa 0.66)[15], but the validity is unknown.

- Movement testing: active, passive, and accessory movement testing. Active and passive ranges are tested in flexion and extension, side bending, and rotation. Quadrant tested can also be done (e.g. extension with rotation). The reliability is fair to moderate, but the validity is unknown.

There are a variety of other tests. For the McKenzie assessment, the reliability is variable depending on the study, and the validity in acute low back pain is unknown, and only modest predictive value in chronic low back pain. Tests of the sacroiliac joint are reliable but their validity in acute low back pain is unknown. In chronic low back pain they have moderate validity.

A neurological examination is not required in the absence of neurological symptoms. If a patient has weakness, numbness, or radicular pain then certainly it is warranted, however the indication is the neurological symptoms, not the back pain. Neurological signs don't present with back pain as the only symptom.

A neurological examination can however be done with the goal of "appearing thorough." In that case a screening examination is sufficient. The L5 and S1 myotomes can be assessed quickly by having the patient walk on their heels and toes. Sensation can be assessed quickly with light touch. The reliability is good (kappa > 0.6).[14][16] Reflex testing isn't needed in the absence of neurological symptoms but can be useful for positive reinforcement to the patient.

An abdominal examination and vascular examination are important for assessing for visceral (e.g. masses) and vascular (abdominal aortic aneurysm) disorders.

The demeanor of the patient can be helpful in identifying serious causes. Some patients with conditions like discitis or cancer can just "look unwell," with a serious and quietly guarded presentation. The aphorism is beware the quiet patient with severe pain.

It is important to explain what you are doing during the examination, i.e. what is being done and what is found. Give the patient positive feedback when positive findings are found. For example when testing the reflexes explain that a good reflex means that there is no blockage of signal. If they move well tell them. If their back muscles seem strong again tell them that their back seems strong and that their muscles are in good shape.

Investigations

Overview

If a red flag condition is suspected then appropriate investigations should be done. Such investigations are not recommended as part of the routine assessment of low back pain, as they are not designed to investigate the cause of back pain. They also aren't screening tests in the absence of concern.

| Category | Clinical Features | Specific conditions | Investigations |

|---|---|---|---|

| Simple low back pain | No risk factors | N/A | Nil. Reassess after 4 to 6 weeks if no improvement |

| Primary tumours (rare, 0.04% of all tumours) | myeloma | Myeloma screen | |

| bone and cartilage tumours | Imaging | ||

| Secondary tumours (0.7%) | History of cancer, age greater than 50, failure to improve, weight loss, pain not relieved by rest | Prostate | Calcium, ALP, PSA, ESR and/or CRP, imaging |

| Breast, lung, thyroid, kidney, gastrointestinal, melanoma | Plain radiography, ESR and/or CRP. If radiograph normal but elevated markers then MRI. | ||

| Infection | fever, sweating, immunosupression, dialysis, IVDU, invasive procedure, trauma to skin or mucous membrane, diabetes, alcoholism | Osteomyelitis, epidural abscess | MRI if moderate to high risk. ESR and/or CRP if low risk, with MRI if elevated. |

| Fracture | Significant trauma | Vertebral compression fracture | Plain radiograph |

| Mild trauma in the elderly or history or risk factors for osteoporosis, elderly | Vertebral compression fracture | Plain radiograph | |

| Sporting activity involving extension, rotation, or both. | Stress fracture | Bone scan or MRI | |

| Spondyloarthropathy (0.3 - 0.9%) | Ankylosing spondylitis | ESR and/or CRP | |

| Metabolic bone disease | Paget's disease, Hyperparathyroidism | Calcium | |

| Visceral disease | Smoking, hypertension, palpable mass | Aortic aneurysm | Abdominal exam, ultrasound (e.g. bedside) |

| Retroperitoneal disease | Abdominal exam, ultrasound (e.g. bedside) | ||

| Pelvic disease | Pelvic examination, rectal examination | ||

| Modified from Bogduk et al. Management of Acute and Chronic Low Back Pain. Elsevier 2002. | |||

Radiographs

- Main article: Lumbar Spine Radiographs

Deyo and Diehl validated criteria for lumbar spine radiographs when screening for red flag conditions.[17] However using these criteria can lead to an increased rate of radiograph utilisation. Some of their criteria like over 50 and seeking compensation criteria can generally be relaxed. It may be better to use one's own intuitive protocol. Bogduk, using findings from other studies like from Reinus et al[18], re-cast their criteria as follows:[19]

- History of cancer

- Significant trauma

- Weight loss

- Temperature > 37.8

- Risk factors for infection

- Neurological deficit

- Minor trauma in patients

- Over the age of 50 years, or

- Known to have osteoporosis, or

- Taking corticosteroids

- No improvement over one month

In other cases plain radiographs are not indicated as a routine investigation for acute low back pain. Patients often have misconceptions about the diagnostic validity and need for lumbar spine radiographs. They may incorrectly think that radiographs will show the problem, that a normal radiograph excludes serious problems, and that they are completely safe. Careful communication is required around these misconceptions.

A controlled study found that careful communication only moderately reduced these misconceptions around radiographs but there were no differences in patient satisfaction.[20] Also one study has shown no difference to outcome[21], while another found worse outcomes at 3 months.[22]

Advanced Imaging

- See also: Lumbar Spine MRI

CT imaging is not indicated as a screening tool in low back pain. Likewise MRI is not justified in the investigation of acute low back pain, even as a screen for red flag conditions. This is in contrast to chronic low back pain where it does have some validity as a screening test and can provide an imperfect aid in identifying the source of pain.[19]

A randomised study comparing early MRI or CT versus delayed imaging until clinical need found no different in outcome.[23]

See Lemmers et al for a systematic review on the costs, healthcare utilisation, and absence from work associated with spinal imaging.[24]

Bone scanning is not commonly done in acute low back pain in New Zealand. It has typically been studied as a modality for detecting acute pars fractures, but they are an imperfect tool with a high false negative rate, and a very low yield of positive scans. If a scan is positive a radiograph should be performed to detect a fracture, if there is no fracture then rest should be advised to avoid progression to fracture. If the bone scan and radiograph are both positive then the fracture may be recent but it isn't guaranteed to be the source of pain, however it may still be possible for bony healing to occur.[19]

Explanation

- See also: Good Back Consultation

References

- ↑ 1.0 1.1 Wade King and Nikolai Bogduk. Acute Low Back Pain. Bonica's Management of Pain. 2018

- ↑ Bogduk et al. Medical Management of Acute and Chronic Low Back Pain. Chapter 3. Elsevier 2002.

- ↑ Itz CJ, Geurts JW, van Kleef M, Nelemans P. Clinical Course of Non-Specific Low Back Pain: A Systematic Review of Prospective Cohort Studies Set in Primary Care. Eur J Pain. 2013;17(1):5-15. doi: 10.1002/j.1532-2149.2012.00170.x.

- ↑ Machado GC, et al. Can Recurrence After an Acute Episode of Low Back Pain Be Predicted? Phys Ther. 2017 Sep 1;97(9):889-895. doi: 10.1093/ptj/pzx067. PMID: 28969347

- ↑ National Health Committee. Low Back Pain: A Pathway to Prioritisation. 2015. Full Text

- ↑ Bogduk et al. Management of Acute and Chronic Low Back Pain. Chapter 5. Elsevier 2002

- ↑ Bogduk et al. Medical Management of Acute and Chronic Low Back Pain: An Evidence Based Approach. Elsevier Science. 2002

- ↑ 8.0 8.1 Bogduk et al. Chapter 10 Psychosocial Assessment In: Medical Management of Acute and Chronic Low Back Pain. Elsevier 2002

- ↑ Sowden G, Hill JC, Konstantinou K, Khanna M, Main CJ, Salmon P, Somerville S, Wathall S, Foster NE; IMPaCT Back study team. Targeted treatment in primary care for low back pain: the treatment system and clinical training programmes used in the IMPaCT Back study (ISRCTN 55174281). Fam Pract. 2012 Feb;29(1):50-62. doi: 10.1093/fampra/cmr037. Epub 2011 Jun 27. PMID: 21708984; PMCID: PMC3261797.

- ↑ Hill JC, Whitehurst DG, Lewis M, Bryan S, Dunn KM, Foster NE, Konstantinou K, Main CJ, Mason E, Somerville S, Sowden G, Vohora K, Hay EM. Comparison of stratified primary care management for low back pain with current best practice (STarT Back): a randomised controlled trial. Lancet. 2011 Oct 29;378(9802):1560-71. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(11)60937-9. Epub 2011 Sep 28. PMID: 21963002; PMCID: PMC3208163.

- ↑ Cherkin D, Balderson B, Wellman R, Hsu C, Sherman KJ, Evers SC, Hawkes R, Cook A, Levine MD, Piekara D, Rock P, Estlin KT, Brewer G, Jensen M, LaPorte AM, Yeoman J, Sowden G, Hill JC, Foster NE. Effect of Low Back Pain Risk-Stratification Strategy on Patient Outcomes and Care Processes: the MATCH Randomized Trial in Primary Care. J Gen Intern Med. 2018 Aug;33(8):1324-1336. doi: 10.1007/s11606-018-4468-9. Epub 2018 May 22. PMID: 29790073; PMCID: PMC6082187.

- ↑ Darlow B, Stanley J, Dean S, Abbott JH, Garrett S, Wilson R, Mathieson F, Dowell A. The Fear Reduction Exercised Early (FREE) approach to management of low back pain in general practice: A pragmatic cluster-randomised controlled trial. PLoS Med. 2019 Sep 9;16(9):e1002897. doi: 10.1371/journal.pmed.1002897. PMID: 31498799; PMCID: PMC6733445.

- ↑ Bogduk et al. Management of Acute and Chronic Low Back Pain. Chapter 7. Elsevier 2002.

- ↑ 14.0 14.1 Waddell G, Main CJ, Morris EW, Venner RM, Rae PS, Sharmy SH, Galloway H. Normality and reliability in the clinical assessment of backache. Br Med J (Clin Res Ed). 1982 May 22;284(6328):1519-23. doi: 10.1136/bmj.284.6328.1519. PMID: 6211214; PMCID: PMC1498438.

- ↑ Njoo KH, van der Does E, Stam HJ. Interobserver agreement on iliac crest pain syndrome in general practice. J Rheumatol. 1995 Aug;22(8):1532-5. PMID: 7473479.

- ↑ McCombe PF, Fairbank JC, Cockersole BC, Pynsent PB. 1989 Volvo Award in clinical sciences. Reproducibility of physical signs in low-back pain. Spine (Phila Pa 1976). 1989 Sep;14(9):908-18. doi: 10.1097/00007632-198909000-00002. PMID: 2528822.

- ↑ Deyo RA, Diehl AK. Lumbar spine films in primary care: current use and effects of selective ordering criteria. J Gen Intern Med. 1986 Jan-Feb;1(1):20-5. doi: 10.1007/BF02596320. PMID: 2945915.

- ↑ Reinus WR, Strome G, Zwemer FL Jr. Use of lumbosacral spine radiographs in a level II emergency department. AJR Am J Roentgenol. 1998 Feb;170(2):443-7. doi: 10.2214/ajr.170.2.9456961. PMID: 9456961.

- ↑ 19.0 19.1 19.2 Bogduk et al. Management of Acute and Chronic Low Back Pain. Chapter 8 Imaging. Elsevier 2002

- ↑ Deyo RA, Diehl AK, Rosenthal M. Reducing roentgenography use. Can patient expectations be altered? Arch Intern Med. 1987 Jan;147(1):141-5. doi: 10.1001/archinte.147.1.141. PMID: 2948466.

- ↑ Kendrick D, Fielding K, Bentley E, Kerslake R, Miller P, Pringle M. Radiography of the lumbar spine in primary care patients with low back pain: randomised controlled trial. BMJ. 2001 Feb 17;322(7283):400-5. doi: 10.1136/bmj.322.7283.400. PMID: 11179160; PMCID: PMC26570.

- ↑ Ferriman A. Early x ray for low back pain confers little benefit. BMJ. 2000 Dec 16;321(7275):1489. PMID: 11118171; PMCID: PMC1119214.

- ↑ Gilbert FJ, Grant AM, Gillan MG, Vale LD, Campbell MK, Scott NW, Knight DJ, Wardlaw D; Scottish Back Trial Group. Low back pain: influence of early MR imaging or CT on treatment and outcome--multicenter randomized trial. Radiology. 2004 May;231(2):343-51. doi: 10.1148/radiol.2312030886. Epub 2004 Mar 18. PMID: 15031430.

- ↑ Lemmers GPG, van Lankveld W, Westert GP, van der Wees PJ, Staal JB. Imaging versus no imaging for low back pain: a systematic review, measuring costs, healthcare utilization and absence from work. Eur Spine J. 2019 May;28(5):937-950. doi: 10.1007/s00586-019-05918-1. Epub 2019 Feb 22. PMID: 30796513.