Causes and Sources of Chronic Low Back Pain

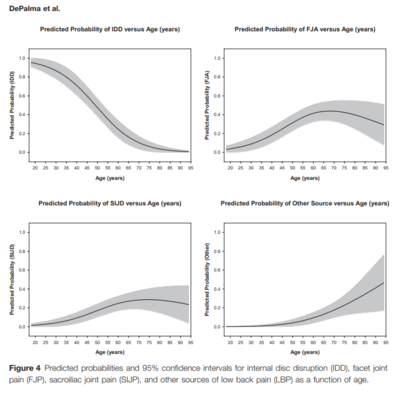

While The causes of acute low back pain are largely unknown, this is not the case for chronic low back pain, where a biomedical diagnosis is possible in the majority of cases. The exact figures depend on the age, but around 40% have disc pain, around 30% have facet joint pain, and around 20% have sacroiliac joint pain.[2]

Definitions

The source of the pain refers to the anatomical structure which has nociceptive activity leading to pain perception. The cause of the pain is the disease process or disorder that is responsible for the nociceptive activity. The most well established causes of chronic low back pain are the lumbar intervertebral discs, and the lumbar zygapophysial joints.

Non-Specific Low Back Pain (~10%)

- Main article: Non-Specific Chronic Low Back Pain

It is often incorrectly stated that the cause of low back pain cannot be diagnosed in 85% of cases with exact figure differing with different publications (some say 80%, some say 90%)[3] This "convenient truth" has been proven to be false time and time again. Unlike acute low back pain where the causes are largely unknown, The causes of chronic low back pain are largely known. History, examination, and radiography are insufficient for diagnosis, but the cause can be established with at least moderate certainty in around 90% of cases as long as there is access to appropriate investigations and the investigations are done in a logical manner.[4][5][6][7][8]

Red Flags

The red flag section in the acute low back pain article is still relevant for chronic low back pain.

Red flag conditions, such as tumours and infections are uncommon, if not rare causes of chronic low back pain. Bogduk provides the following for mathematical illustration:[9]

Pa% = prevalence of serious conditions in patients with acute back pain

Z% = the percentage of patients with a serious cause for acute low back pain that develop chronic low back pain

Pc% = Prevalence of serious condition in patients with chronic low back pain

Then if it is assumed that everyone with a serious condition develops chronic low back pain:

Pc% = (Pa/Z)%

E.g. tumours: P=1%, If 30% of acute patients become chronic, prevalence in chronic low back pain = (1/30)% = 3%

Lumbar Intervertebral Discs

Internal Disc Disruption

- See also: Internal Disc Disruption

Internal disc disruption is a condition that affects lumbar intervertebral discs and is the cause of pain in around 40% of individuals with chronic low back pain. The inciting event is fatigue failure of the vertebral endplate, which leads to degradation of the nuclear matrix. Subsequently radial and circumferential fissures develop that penetrate from the nucleus pulposus through to the anulus fibrosus, however the outer anulus is not breached. Pain is thought to arise through chemical nociception around the fissures ,as well as through mechanical nociception from the degraded nuclear matrix leading to greater loads being placed on the posterior anulus fibrosus.

Internal disc disruption can be diagnosed through special tests.

Degenerative Disc Disease

Internal disc disruption is a separate concept to disc degeneration. While there are many similar processes and features, internal disc disruption is a response to injury that occurs either through single or repetitive compressive loads.[10] Degenerative disc disease does not correlate strongly with back pain, unlike internal disc disruption.

Degenerative changes are an expression of metabolic stress, not a disease. There are no known mechanisms whereby degenerative changes can be painful. There are lots of different triggers with a final common pathway. Degenerative joint disease is a disturbing label that patients associate with a poor prognosis. Genetic factors predispose to degenerative changes, but age is the strongest correlate. Specific metabolic causes are rare, and limited to diabetes mellitus and ochronosis. Impaired nutrition is promoted but the evidence is lacking. Smoking is a weak correlate. Low grade infection has been explored but the evidence is not conclusive.

In the lumbar spine degenerative changes are chemical in nature, expressed as changes in proteoglycan content and hydration. This is seen on MRI with changes in signal intensity.

Chondrocytes maintain the balance between synthesis and degradation of the extracellular matrix. Synthesis is promoted by growth factors. Degradation is achieved by the activation of various enzymes such as the MMP family, whose expression is controlled by various cytokines (see Fibrous Connective Tissues, and Synovial Joints). Osteophytes are simply adaptive modelling, where there is an attempt to increase surface area to reduce load. This can be be a normal joint with excessive load, or joint where the capacity to bear loads is compromised by degradation of the matrix.

With aging, chondrocytes might be subject to innate senescence. They may have genetic abnormalities that affect matrix quality. Normal cells may become impaired with the accumulation of toxins and mechanical stresses. Zygapophysial joints have not been explicitly studied with regards to ageing changes, but come under the umbrella of synovial joints - i.e. the changes are likely a combination of genetics and abnormal biomechanics. For lumbar disc degeneration the evidence is more explicit from twin studies. Environmental influences play a role, but larger proportions are explains by genetic factors.[11]

Discitis

Chemical nociception can occur with irritation of the nociceptive fibres of an infected disc, and this is a red flag condition.

A disputed cause is chronic low grade infection by Propionibacterium acnes. The hypothesis is that vertebral marrow/endplate oedema caused by low grade bacterial discitis

Some studies have isolated Cutibacterium (Propionibacterium) acnes from discs in people undergoing spinal surgery. A systematic review attempted to clarify this and found that this may be related to abnormal discs being more susceptible to infection, but it is difficult to establish true infection versus contamination (some studies also isolated CONS).[12]

In an RCT of 144 patients, there was significant improvement with 100 days of augmentin in chronic low back pain, prior disc herniation, and type 1 Modic changes. Limitations included high proportions of participants having had previous back surgery, no improvement in the control group, and unclear efficacy of blinding.[13]

A multi-centre double blinded RCT was done in an attempt to reproduce the results but it was not successful. See graphic[14]

Zygapophysial Joints

Excessive compression or torsion can lead to microfracture and capsular avulsion of the zygapophysial joints. These post-traumatic structural changes have been shown in laboratory studies and postmortem pathoanatomic studies, but not in any antemortem studies.[15]

- Cervical:

- Face upwards and backwards, therefore equally share compressive load with discs

- Injuries most likely to occur from weight bearing

- Degenerative changes occur at all levels, most commonly C3/4

- Lumbar:

- Face posteriorly and laterally, share little of the axial load

- Resists axial rotation and anterior translation

- Degenerative changes arise earlier, more common in L4/5

Sacroiliac Joints

Structural Abnormalities

Structural abnormalities include congenital abnormalities (congenital fusion, spina bifida occulta, and transitional vertebra), spondylolysis, spondylolisthesis, and spondylosis. As is the case for acute low back pain, these abnormalities are equally common in symptomatic and asymptomatic patients and so cannot be causes of chronic low back pain.[16]

For spondylolysis, only amongst sportspeople are pars defects more common. However simply seeing spondylolysis on plain films does not constitute having found the source of pain. For that a pars block is required, with relief of pain supporting the diagnosis, and predicts success with surgery.[17]

Instability

The term spinal instability is controversial. There are various biomechanical definitions and diagnostic criteria. The musculoskeletal medicine view is that instability does not constitute a diagnosis of chronic low back pain.

The various definitions, which all have limitations include:

- Loss of stiffness in spinal motion segments

- An increase in the neutral zone of intervertebral movements

- Increase in the ratio between the magnitude of translation and the magnitude of rotation that a motion segment exhibits during flexion-extension of the lumbar spine

Instability can also be classified based on the lesions that are postulated to cause the instability.

- Fractures and fracture-dislocations

- Infections of anterior elements

- Neoplasms

- Spondylolisthesis

- Degenerative

In this classification scheme for fractures, infections, and neoplasms one only needs to see the finding, and not demonstrate the instability biomechanically, which is sensible.

For spondylolisthesis, while it can look threatening on radiographs, it rarely progresses, and grade 1 and grade 2 spondylolisthesis is associated with reduced range of motion rather than instability. Further precision studies have shown that motion patterns of patients are indistinguishable from degenerative disc disease.

There are several types of instability that have been attributed to degeneration of the lumbar spine. However there have been no studies proving them as a cause of pain or showing that correcting them resolves pain. These types of instability include:

- Rotational – hypothetical entity, certain radiographic signs may suggest it, but the reliability and validity has not been studied.

- Retrolisthetic – occurs during extension, but this movement can occur in asymptomatic individuals.

- Translational – abnormal forward translation during flexion. There is difficulty in defining the upper limit of normal, with dynamic translations of 4mm occurring in 20% of asymptomatic individuals.

Correlations

- One method is to compare prevalence in people with and without pain. If prev is higher in people with pain, association is established

- Another method is to anesthetize joint. If relieves pain, target joint is implicated as source.

The prevalence of lumbar disc degeneration in asymptomatic individuals, clearly increases with age Radiographic features of cervical spine in asymptomatic people again increases with age (hardly any “normal” looking spines in over 50)

Neck Pain

Study compared patients with neck pain, with controls. There were no differences in prevalence of spondylosis, severe disc changes or facet joint changes between cases and controls. Degenerative changes in cervical discs/z joints do not correlate with pain

Low Back Pain

A large population study looked at osteoarthosis in the context of pain No association with pain, irrespective of grade Many studies on disc degeneration Systematic reviews on high quality studies showed no clinical association between degenerative disc changes and pain

Spondylolisthesis

- Spondylolithesis – translation of 1 vertebral body on another. 6 broad categories – (wiltse classification) isthmic, traumatic, degen, pathologic, dysplastic and post surgical. It can also be classified according to severity (Merding)

- Bogduk – not associated with pain, finding it on xray does not constitute diagnosis. Rarely progresses. Grade 1 – 2 associate with reduced ROM rather than instability.

Degenerative Lumbar Spondylolisthesis

- Incidence 19-43%, mean age 71, most common in females

- Most common L4/5

- Initial event – disc degeneration/narrowing of disc space - micro-instability

- Cause of pain multi factorial

- Most are grade 1 (75%) – less than 25% slip

- Average slip progression – 18%, no correlation between progression and symptoms

- Natural history and management of low grade slip is controversial, conservative management generally indicated. Surgery for refractory cases

Isthmic Lumbar Spondylolisthesis

- Isthmic meaning movement of one vertebrae on another, due to a defect in the pars, termed spondylolysis (unhealed stress fracture). Spondylolysis can be present without displacement. Spondylolistesis occurs in 40-60% of patients with bilateral spondylolysis (unlikely if unilateral).

- Most are asymptomatic, 25% have back/radicular pain

- Prevalence in children 2.6%, increasing to 4% in adult

- Asymptomatic in 3-11% of adults

- More common in men, L5/S1

- Causes are multifactorial, genetic component

- Back pain may be from micro-stability or pain from degenerative disc

- Symptomatic patients are initially treated non-operatively

High grade lumbar sponylolisthesis

- Defined as >50% slippage

- Most are at L5/S1, a result of isthmic spondylolisthesis

- Most have a degree of neurologic compromise

- Pain usually with hyperextension, resolves with time due to fracture union

- Treatment is focused on correction of lordosis and sagittal balance

- Natural history – difficult to predict if further slippage will occur

- Conservative management trialed in adolescence, usually unable to provide permanent relief�

Surgical vs Non Surgical Treatment of Lumbar Spondylolithesis – Karsy et al.

- Non operative effective in patients without neurogenic claudication or radiculopathy and stable spondylolisthesis (grade 1)

- 1/3 show progression over time

- Lumbar decompression alone can be effective for low grade, fusion if higher grade

- Mechanical instability is change of 3mm-6mm between flexion/ext films, or change from sitting to standing

- Meta analysis – surgical intervention is more effective than non operative, for patients with pain and functional limitations

Lumbar instability – J. Beazell

- Historical term, that has been debated through 1980-90’s

- Encompasses two types:

- Mechanical (radiographic)

- Functional (clinical)

- Topic is subject to much debate on exact nature of problem, correlation with history and relevance to patient management

Seminal Journal Articles

Degenerative Joint Disease of the Spine – N. Bogduk. Radiol Clin N Am 50 (2012) 613–628

High-Grade Lumbar Spondylolisthesis – A. Beck et al. Clin N Am 30 (2019) 291-298

Isthmic Lumbar Lumbar Spondylolisthesis – A. Bhalla. Clin N Am 30 (2019) 283-290

Degenerative Lumbar Spondylolisthesis – M. Bydon. Clin N Am 30 (2019) 299-304

Surgical vs Non Surgical Treatment of Lumbar Spondylolisthesis. Clin N Am 30 (2019) 333-340

Lumbar instability: an evolving and challenging concept. J. Beazell. Journal of Manual and Manpulative Therapy. Vol 18 1 (2010)

- ↑ DePalma MJ, Ketchum JM, Saullo T. What is the source of chronic low back pain and does age play a role? Pain Med. 2011 Feb;12(2):224-33. doi: 10.1111/j.1526-4637.2010.01045.x. Epub 2011 Jan 25. PMID: 21266006.

- ↑ DePalma MJ. Diagnostic Nihilism Toward Low Back Pain: What Once Was Accepted, Should No Longer Be. Pain Med. 2015 Aug;16(8):1453-4. doi: 10.1111/pme.12850. Epub 2015 Jul 27. PMID: 26218010.

- ↑ Fitzcharles MA, Cohen SP, Clauw DJ, Littlejohn G, Usui C, Häuser W. Nociplastic pain: towards an understanding of prevalent pain conditions. Lancet. 2021 May 29;397(10289):2098-2110. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(21)00392-5. PMID: 34062144.

- ↑ DePalma et al.. What is the source of chronic low back pain and does age play a role?. Pain medicine (Malden, Mass.) 2011. 12:224-33. PMID: 21266006. DOI.

- ↑ DePalma et al.. Etiology of chronic low back pain in patients having undergone lumbar fusion. Pain medicine (Malden, Mass.) 2011. 12:732-9. PMID: 21481166. DOI.

- ↑ DePalma et al.. Multivariable analyses of the relationships between age, gender, and body mass index and the source of chronic low back pain. Pain medicine (Malden, Mass.) 2012. 13:498-506. PMID: 22390231. DOI.

- ↑ DePalma et al.. Structural etiology of chronic low back pain due to motor vehicle collision. Pain medicine (Malden, Mass.) 2011. 12:1622-7. PMID: 21958329. DOI.

- ↑ DePalma. Diagnostic Nihilism Toward Low Back Pain: What Once Was Accepted, Should No Longer Be. Pain medicine (Malden, Mass.) 2015. 16:1453-4. PMID: 26218010. DOI.

- ↑ Bogduk and McGuirk. Causes and sources of chronic low back pain In: Medical Management of Acute and Chronic Low Back Pain. Elsevier 2002

- ↑ Bogduk N, Aprill C, Derby R. Lumbar discogenic pain: state-of-the-art review. Pain Med. 2013 Jun;14(6):813-36. doi: 10.1111/pme.12082. Epub 2013 Apr 8. PMID: 23566298.

- ↑ Battié MC, Videman T, Kaprio J, Gibbons LE, Gill K, Manninen H, Saarela J, Peltonen L. The Twin Spine Study: contributions to a changing view of disc degeneration. Spine J. 2009 Jan-Feb;9(1):47-59. doi: 10.1016/j.spinee.2008.11.011. PMID: 19111259.

- ↑ Urquhart DM et al. Could low grade bacterial infection contribute to low back pain? A systematic review.BMC Med 2015;13:13.

- ↑ Albert H, Sorensen J, Christensen B, Manniche C. Antibiotic treatment in patients with chronic low back pain and vertebral bone edema (Modic type 1 changes): a double-blind randomized clinical controlled trial of efficacy.Eur Spine J.2013;22:697–707

- ↑ Bråten LCH, Rolfsen MP, Espeland A, et al. Efficacy of antibiotic treatment in patients with chronic low back pain and Modic changes (the AIM study): double blind, randomised, placebo controlled, multicentre trial [published correction appears in BMJ. 2020 Feb 11;368:m546]. BMJ. 2019;367:l5654. Published 2019 Oct 16. doi:10.1136/bmj.l5654

- ↑ Wade King and Nikolai Bogduk. Chronic Low Back Pain In: Bonica's Management of Pain. 2018

- ↑ van Tulder MW, Assendelft WJ, Koes BW, Bouter LM. Spinal radiographic findings and nonspecific low back pain. A systematic review of observational studies. Spine (Phila Pa 1976). 1997 Feb 15;22(4):427-34. doi: 10.1097/00007632-199702150-00015. PMID: 9055372.

- ↑ Suh PB, Esses SI, Kostuik JP. Repair of pars interarticularis defect. The prognostic value of pars infiltration. Spine (Phila Pa 1976). 1991 Aug;16(8 Suppl):S445-8. PMID: 1785102.