Chronic Low Back Pain

Chronic low back pain is a common cause of persistent suffering and disability for the affected individual, but also has significant effects on those around them. The biomedical assessment involves determining whether they have the IASP definition of low back pain, whether it is indeed chronic, ascertaining whether they have referred pain and whether it is somatic referred pain or radicular pain, and identifying "red flag" conditions. A decision is then made about whether to go down an investigative pathway to determine the source and cause of the pain. Treatment approaches include monotherapies (e.g. physiotherapy, surgery, medication), multi-disciplinary treatments, and reductionist treatments if a precision diagnosis is made and a relevant treatment is available, efficacious, and acceptable to the patient (e.g. medial branch radiofrequency neurotomy for confirmed facet joint pain).

Definitions

- Main article: Low Back Pain Definitions

Topography

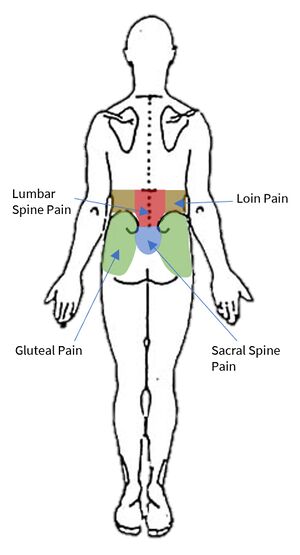

Starting with the wrong definition of low back pain can lead to the wrong diagnosis, and so it is important to be clear here. Low back pain is not loin pain, nor is it gluteal pain. The IASP taxonomy categorises low back pain into lumbar spinal pain and sacral spinal pain. There is also an overlapping definition called lumbosacral pain. These three categories constitute the colloquial term "low back pain."

Lumbar spinal pain is pain in a region bounded superiorly by an imaginary transverse line through the tip T12, inferiorly by an imaginary transverse line through the tip of S1, and laterally by vertical lines tangential to the lateral margins of the erector spinae muscles.

Sacral Spinal Pain is pain in a region bounded superiorly by an imaginary transverse line through the tip of S1, inferiorly by an imaginary transverse line through the posterior sacrococcygeal joints, and laterally by imaginary lines passing through the posterior superior and posterior inferior iliac spines."

Lumbosacral Pain is pain perceived as arising from a region encompassing or centred over the lower third of the lumbar region as described above and the upper third of the sacral region as described above.

Acuity

Chronic pain is pain present for longer than 3 months (91 days). One pragmatic approach is to include in the definition of chronic those patients with acute low back pain who are not improving when it may not be sensible to wait until the 91 day mark, say at two months. However if they have had pain for more than two months and not had evidence based management for acute low back pain then they should have that first. Indeed, following the acute approach may still be appropriate for some patients who have had pain for longer than 3 months.

Referred Pain

- Main article: Low_Back_Pain_Definitions#Referred_Pain

Referred pain is "pain perceived as arising or occurring in a region of the body innervated by nerves or branches of nerves other than those that innervate the actual source of pain"

Visceral referred pain is referred pain where the source lies in an organ or blood vessel of the body. With low back pain, the uterus and abdominal aorta are important considerations. Other viscera with higher segmental supply may cause back pain such as pancreatitis, but this may be due to irritation of the posterior abdominal wall, in which case the pain is not truly referred in nature.

Somatic referred pain is referred pain where the source originates in a tissue or structure of the body wall or limbs. A number of structures in the lumbar spine are capable of nociception including the lumbar zygapophysial joints, intervertebral discs, sacroiliac joints, and more.

Radicular pain is a subset of neuropathic pain, and refers to pain that is evoked with stimulation of the nerve roots or dorsal root ganglion of a spinal nerve. In radicular pain, the pain is felt in the peripheral innervation of the affected nerve.

Somatic referred pain and radicular pain can usually be differentiated based on the quality and spread of the pain, see the assessment section below.

Aetiology

- Main article: Causes and Sources of Chronic Low Back Pain

Various structures in the low back are capable of nociception as determined through noxious stimulation, including the muscles, interspinous ligaments, zygapophysial joints, sacroiliac joints, and the intervertebral discs which are the most sensitive. These constitute possible sources of pain.[2]

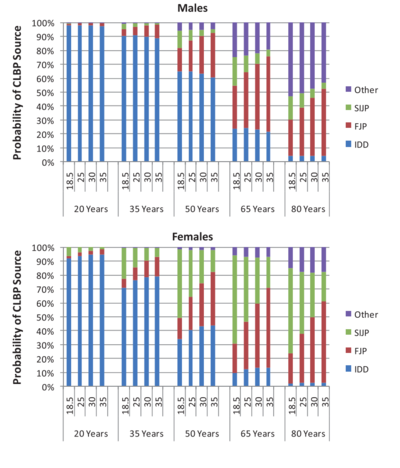

As for the causes, the lumbar intervertebral discs and lumbar zygapophysial joints have the most evidence as established causes. The sacroiliac joint has the next best evidence. The prevalence is highly dependent on the age, and also the BMI and gender.[1] Overall around 40% have disc pain, around 30% have facet joint pain, and around 20% have sacroiliac joint pain.[3] The common aphorism that "most chronic low back pain is non-specific" is out of date and patently false, especially in those without widespread chronic pain.

Assessment

The assessment of chronic low back pain has some slight modifications to that of acute low back pain. History is still important, while physical examination still has major limitations. Imaging however now plays a greater role. The doctor must take care to avoid missing any serious causes of pain, formulate a diagnosis, instigate an investigation and treatment plan, and identify and manage any psychosocial barriers to recovery. Unlike with acute low back pain, a precise diagnosis is often possible for chronic low back pain. A decision is made whether to pursue a definitive diagnosis to enable specific targeted treatment, or apply general treatments that don't require precise source identification.

Pain History

- See also: Acute Low Back Pain#Pain History, Medical History

The age of the patient is of vital importance. This is because the potential causes are dependent on age, as well as certain malignancies.

The site of pain helps to determine the taxonomy, whether they have lumbar spine pain, loin pain, gluteal pain, or abdominal pain, each of which have a different assessment and management. Abdominal pain takes priority over low back pain.

For sacroiliac joint or sacroiliac ligament pain, the site of pain tends to be over the sacroiliac region below the L5 level. So pain below L5 increases the odds of the sacroiliac complex being implicated.

The duration of illness establishes whether they have chronic pain as it is defined, and make some sort of assessment as to the likelihood of red flag conditions. The idea being that pain present for a long time without deterioration may suggest a low risk of red flags. However certain infections and tumours can develop very slowly.

The distribution of pain its quality helps distinguish between somatic referred and radicular pain. (see article on referred pain). These two entities are commonly confused.

| Somatic Referred | Radicular | |

|---|---|---|

| Pain quality | Dull, deep ache, or pressure-like, perhaps like an expanding pressure | Shooting, lancinating, or electric-shocks |

| Relation to back pain | Referred pain is always concurrent with back pain. If the back pain ceases then so does the referred pain. If the back pain flares then so does the leg pain intensity and spatial spread. | Not always concurrent with back pain. |

| Distribution | Anywhere in the lower limb, fixed in location, commonly in the buttock or proximal thigh. Spread of pain distal to the knee can occur when severe even to the foot, and it can skip regions such as the thigh. It can feel like an expanding pressure into the lower limb, but remains in location once established without traveling. It can wax and wane, but does so in the same location. | Entire length of lower limb, but below knee > above knee. In mild cases the pain may be restricted proximally. |

| Pattern | Felt in a wide area, with difficult to perceive boundaries, often demonstrated with an open hand rather than pointing finger. The centres in contrast can be confidently indicated. | Travels along a narrow band no more than 5-8 cm wide in a quasi-segmental fashion but not related to dermatomes (dynatomal). |

| Depth | Deep only, lacks any cutaneous quality | Deep as well as superficial |

| Neurological signs | Not characteristic | Favours radicular pain, but not required. |

| Neuroanatomical basis | Discharge of the peripheral nerve endings of Aδ and C fibres from the lower back converge onto second order neurons in the dorsal horn that also receive input from from the lower limb, and so the frontal lobe has no way of knowing where the pain came from. | Heterotopic discharge of Aδ, Aβ, and C fibres through stimulation of a dorsal root or dorsal root ganglion of a spinal nerve, typically in the presence of inflammation, with pain being felt in the peripheral innervation of the affected nerve |

The intensity of pain can be recoded using the VAS or NRS scale. For those individuals where pain fluctuates, record the average intensity during activity, and the worst pain recently. Pain intensity is the single most significant patient factor for decision about seeking medical care, and so the pain is likely to be significant enough to them regardless of the actual figure given. Sometimes patients may indicate very high pain scores such as "12/10" and this may reflect suffering and psychological distress. The intensity of pain can be useful for recording a baseline, monitoring progress, and judging the effectiveness of treatment.

There is no association between pain intensity and how likely it is that the cause of the pain is due to a serious condition.

Widespread Pain

It should be determined whether there is widespread pain, as widespread pain may indicate a more systemic condition such as rheumatological conditions, fibromyalgia, central sensitisation, or controversially some heritable connective tissue disorders. These categories of patients can still nonetheless have the standard causes and sources of chronic low back pain, but the assessment and management is made much more difficult.

Widespread pain should not be confused with somatic referred pain: the latter does not spread cranially. Another common pitfall is assuming that multiple concurrent primary nociceptive drivers can't co-exist. For example symptomatic hip osteoarthritis and lateral elbow tendinopathy are both very common conditions, and may occur simultaneously as separate primary nociceptive conditions through aleotoric processes (See article on uncertainty). A single "unifying diagnosis" of central sensitisation may not apply here. Here we see the opposing aphorisms of Occams razor ("entities should not be multiplied beyond necessity") and Hickams dictum ("patients can have as many diseases as they damn well please"). Each individual affected region should be assessed on its own merit.

In someone with multiple areas of pain, "solving" the low back pain of someone with widespread chronic pain pain may not reduce their overall pain score or improve their overall function. The clinician can end up moving around the body of the patient over years without any significant overall improvement. Some consider such patients to be best served by a multidisciplinary pain clinic, but this is not a hard and fast rule. In those where MDT is not acceptable or suitable, one approach is to address the "worst area" (patient defined) first.

Red Flags

- See also: Acute Low Back Pain#Red Flags

The same red flags in acute low back pain can be used for chronic low back pain. Any red flags that are identified prompts further consideration for a serious conditions, which may include investigation. They are not diagnostic or such conditions, and are not designed to have great positive predictive power. They were developed on the basis of case reports of unusual causes that were overlooked during assessment but could have been identified if the appropriate question was asked.[2]

If there are no positive responses then the likelihood of a serious condition is extremely low. In the presence of neurological features, this complicates the presentation, and investigating this becomes more important than investigating the cause of the back pain, as the investigations are not always the same.

- History of: Trauma, sports injury, fever, night sweats, recent surgery, catheterisation, venipuncture, illicit drug use, weight loss, cancer, occupational exposure, hobby exposure, overseas travel, pain severe worsening or unremitting especially at night

- Cardiovascular: Risk factors

- Respiratory: Cough in a smoker or ex-smoker

- Gentio-urinary: Infection, haematuria, retention, stream problems

- Gynaecological: abnormal uterine bleeding, dysmenorrhoea

- Haematological

- Endocrine: Diabetes, corticosteroids, parathyroid

- Musculoskeletal: pain elsewhere

- Neurologic: symptoms/signs including for cauda equina compression

- Skin: Infection, rashes

- Gastrointestinal: Diarrhoea, inflammatory bowel disease

- Demographic: Aged over 50 years with first episode, especially age over 65 years

Psychosocial Assessment

Much of the same psychosocial assessment principles in acute low back pain apply. Of importance is that diagnoses such as "factitious disorder" and "malingering" have no valid operational criteria for diagnosis, and should not be used. A similar related concept is "secondary gain" and this too has weak scientific support. "Secondary losses" generally outweigh any "secondary gains," and so it does not constitute a diagnosis.[5]

Various questionnaires have been developed to identify psychological features such as fear avoidance, kinesiophobia, catastrophising, depression, and anxiety. Such features can account for some of the disability a patient is experiencing as a result of their pain. Such patients may be pre-occupied with their pain, depressed, and feel unable to do anything about it, and be focused on passive therapies.

Psychological symptoms are generally a consequence of experiencing chronic pain in susceptible individuals, they are not indicative of the reverse i.e. the pain arising from psychosocial distress. In the biopsychosocial model, the biological features are essential to the experience of pain. The maladaptive response to the pain experience would not exist without the pain experience itself. However the doctor should be aware of any related psychosocial issues.[2]

However, patients with high levels of psychological distress tend to respond poorly to conventional biomedical treatment. Identifying high levels of distress may cause pause for the doctor. Further biomedical treatments that are destined to fail can lead to cycles of hope and despair, exacerbating the patients psychological distress.

Physical Examination

- Main article: Lumbar Spine Examination

As for acute low back pain, the physical examination is not able to make a reliable patho-anatomic diagnosis in chronic low back pain (see examination section in acute low back pain). The same is true for a neurological examination. Neurological signs indicate a neurological disorder and this should be investigated within its own merits.

The reliability and validity of the physical examination has been studied with regards to the three most common causes of chronic low back pain: internal disc disruption, facet joint pain, and sacroiliac joint pain.

For internal disc disruption, a positive centralisation response under the McKenzie assessment method has a positive LR of 2.4.[6] In a 50 year old male this increases probability from ~60% to ~80%, but in a person over 65 it rises from ~5-20% to ~10-40%.

For facet joint pain there are no diagnostic examination findings. However certain combinations of features may suggest a facet joint origin: age greater than 65; pain relieved by recumbency; and absence of aggravation of pain by coughing, forward flexion, rising from flexion, hyperextension, and extension-rotation. Five or more features has a positive LR of 3.0.[7] In a 50 year old the pre-test probability rises from ~20% to ~40%, and in a person over 65 the pre-test probability rises from ~30% to ~55%.

For sacroiliac joint pain there is the cluster of Laslett.

The "Wadell's inorganic tests" are not appropriate for clinical use as they are neither diagnostic nor predictive. They were designed to identify patients in need of psychosocial assessment, but became abused to identify non-genuine patients. They are not a basis of denying biopsychosocial treatment. Furthermore they don't actually predict failure to return to work.[5]

Investigations

Failure to improve is a criterion for checking for red flag conditions. The question remains what is the most appropriate screening test, of which MRI is the current best modality.

Plain Radiography

- Main article: Lumbar Spine Radiographs

Plain films can detect bone lesions such as myeloma and metastases, but may miss these if early. They also don't detect serious lesions of soft tissues. Therefore x-rays can't fully exclude serious conditions. Furthermore they have a risk of detecting issues such as spondylosis or "degenerative change" that are not causes of pain but might lead to patient misunderstanding and distress. CT has some similar issues however it may detect neurological conditions, but is not available in primary care.

MRI

- Main article: Lumbar Spine MRI

MRI can visualise both bones and soft tissues. It has high sensitivity and specificity, and is safe. It is therefore the best available screening test on face value. Plain films and CT are inferior options. The major limitations are the high cost (around $1500 privately) and the low pick-up rate for serious conditions. Despite widespread availability in New Zealand the cost has not come down, unlike the situation in Australia. ACC and Southern Cross both run a scheme for GP access, but the criteria are very strict. For example low back pain with radicular pain a sensory radiculopathy does not qualify.

Like with plain films, there are many findings on MRI that do not constitute a diagnosis. These include disc bulges and degenerative changes. However high intensity zones and Modic changes (endplate changes) are relevant to chronic low back pain.

High Intensity Zone

High-intensity zones (HIZ) can occur in the innervated posterior anulus of lumbar intervertebral discs. They are seen on T2 weighted images as a bright signal surrounded by dark signal of surrounding fibres. It reflects a circumferential grade IV anular tear, best seen in a sagittal section, but can also correlate with a grade III tear. The brightness should be similar or exceed the brightness of the CSF, it is not just any white spot in the anulus.

Some authors state it is not a valid sign because it occurs in asymptomatic patients. The second statement is true, it is not pathognomonic, but it is more common in symptomatic patients and in a patient with chronic low back pain where the pre-test probability of discogenic pain is already high, it strongly indicates that the affected disc is the source of the pain. Many clinical tests in medicine are not pathognomonic (e.g. ANA) but still have utility.

Endplate Changes

Endplate changes, either type 1 or type 2, are associated with the disc being painful. They also predict response to basivertebral nerve ablation.[8]

Management

Laerum et al outlined what a "Good Back Consultation" entails, based on three interdisciplinary Norwedgian RCTs for chronic low back pain.[9]

- Take them seriously

- Examination: explanation during the exam (what was being done and what was found)

- Education: Providing an understandable explanation for the pain given with conviction (exact medical diagnosis is not essential) and addressing misconceptions. He uses a disc injury explanation.

- Reassurance: given with conviction, address fears but cognitive reassurance is preferred over emotional which can create dependency.

- Psychosocial discussion: deal with possible correlation (in both directions) between daily life, job, family, coping, quality of life aspects, role function and the LBP

- Treatment: Encourage normal activity and avoiding rest. Empower the patient to take responsibility for their own rehabilitation.

References

- ↑ 1.0 1.1 DePalma MJ, Ketchum JM, Saullo TR. Multivariable analyses of the relationships between age, gender, and body mass index and the source of chronic low back pain. Pain Med. 2012 Apr;13(4):498-506. doi: 10.1111/j.1526-4637.2012.01339.x. Epub 2012 Mar 5. PMID: 22390231.

- ↑ 2.0 2.1 2.2 Wade King and Nikolai Bogduk. Chronic Low Back Pain In: Bonica's Management of Pain. 2018

- ↑ DePalma MJ. Diagnostic Nihilism Toward Low Back Pain: What Once Was Accepted, Should No Longer Be. Pain Med. 2015 Aug;16(8):1453-4. doi: 10.1111/pme.12850. Epub 2015 Jul 27. PMID: 26218010.

- ↑ Bogduk et al. Medical Management of Acute and Chronic Low Back Pain: An Evidence Based Approach. Elsevier Science. 2002

- ↑ 5.0 5.1 Bogduk and McGuirk. Assessment In: Medical Management of Acute and Chronic Low Back Pain. Elsevier 2002.

- ↑ Donelson R, Aprill C, Medcalf R, Grant W. A prospective study of centralization of lumbar and referred pain. A predictor of symptomatic discs and anular competence. Spine (Phila Pa 1976). 1997 May 15;22(10):1115-22. doi: 10.1097/00007632-199705150-00011. PMID: 9160470.

- ↑ Revel M, Poiraudeau S, Auleley GR, Payan C, Denke A, Nguyen M, Chevrot A, Fermanian J. Capacity of the clinical picture to characterize low back pain relieved by facet joint anesthesia. Proposed criteria to identify patients with painful facet joints. Spine (Phila Pa 1976). 1998 Sep 15;23(18):1972-6; discussion 1977. doi: 10.1097/00007632-199809150-00011. PMID: 9779530.

- ↑ Fischgrund JS, et al. Intraosseous Basivertebral Nerve Ablation for the Treatment of Chronic Low Back Pain: 2-Year Results From a Prospective Randomized Double-Blind Sham-Controlled Multicenter Study. Int J Spine Surg. 2019 Apr 30;13(2):110-119. doi: 10.14444/6015. PMID: 31131209; PMCID: PMC6510180.

- ↑ Laerum E, Indahl A, Skouen JS. What is "the good back-consultation"? A combined qualitative and quantitative study of chronic low back pain patients' interaction with and perceptions of consultations with specialists. J Rehabil Med. 2006 Jul;38(4):255-62. doi: 10.1080/16501970600613461. PMID: 16801209.