Sacroiliac Joint Pain: Difference between revisions

(general content editing) |

(general content addition) |

||

| Line 58: | Line 58: | ||

It is important to get details of any prior trauma, spinal fusion, and pregnancy history. See the pathophysiology section above. | It is important to get details of any prior trauma, spinal fusion, and pregnancy history. See the pathophysiology section above. | ||

Exacerbating activities can be divided into unilateral weight bearing (putting on socks/shoes, ascending/descending stairs, getting in/out of car, prolonged walking), sexual intercourse pain, pain with transitional movements (supine to painful side, sit to stand, rolling over in bed, getting in/out of bed), and pain while stationary (sitting on affected side, prolonged standing/sitting).<ref name="janda">Janda V. On the concept of postural muscles and posture in man. Aust J Physiotherapy. 1983;29:83-90</ref> | |||

Common relieving factors are bearing weight on the unaffected side, lying on the unaffected side, and manual or belt stabilisation.<ref name="janda"/> | Common relieving factors are bearing weight on the unaffected side, lying on the unaffected side, and manual or belt stabilisation.<ref name="janda"/> | ||

Sacroiliac joint dysfunction can cause neurological symptoms such as numbness, tingling, and weakness.<ref name="timgren"/> | |||

===Examination=== | ===Examination=== | ||

| Line 66: | Line 68: | ||

Complete inspection, palpation, range of motion, gait, and neurological tests. | Complete inspection, palpation, range of motion, gait, and neurological tests. | ||

Asking the patient to point where their primary pain is called the "Fortin finger test" is a test of pointing within 1cm inferomedial of the PSIS, consistent over at least 2 trials (e.g. beginning and end of exam). If the pointed area is below L5 then consider the sacroiliac joint. If it is above L5 then consider lumbar spine aetiology.<ref>{{#pmid:9247654}}</ref> Tenderness over the PSIS and sacral sulcus may be a good indicator of a pain source. | |||

Do a single leg stance, functional testing (stairs, sit to stand), active straight leg raise, and provocative testing. There may be a lurching and hobbling gait. | Do a single leg stance, functional testing (stairs, sit to stand), active straight leg raise, and provocative testing. There may be a lurching and hobbling gait. | ||

Provocative testing involves the distraction test, thigh thrust test, FABER test, and compression test. 2 out of 4 positive tests confer a higher likelihood of the sacroiliac joint being the source of pain (sensitivity 88%, specificity 78%, LR+ 4.0, LR- -0.16).<ref>{{#pmid:16038856}}</ref> | Provocative testing involves the distraction test, thigh thrust test, FABER test, and compression test. 2 out of 4 positive tests confer a higher likelihood of the sacroiliac joint being the source of pain (sensitivity 88%, specificity 78%, LR+ 4.0, LR- -0.16).<ref>{{#pmid:16038856}}</ref> The provocative tests should be done in gradual increasing stages of pressure, stopping when positive. | ||

The [https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=qhDv5ZmQFhs active straight leg raise test] was studied in pregnancy to test for functional pelvic stability (sensitivity 87%, specificity 94%).<ref>{{#pmid:11413432}}</ref> | |||

;Hip Examination | |||

{{main|Hip Examination}} | |||

It is very important to do a hip examination. Examine FABER (pain anterior for intra-articular hip pathology, sensitivity 88%), Scour (for hip OA and other pathologies, sensitivity 62-91%, specificity 43-75%s), and FADIR (for FAI and labral tears, sensitivity 75%, specificity 43%). The rare pririformis syndrome can be tested for with the FAIR test (sensitivity 88%, specificity 83%). The most predictive finding for osteoarthritis is restriction of internal rotation (severe OA sensitivity 100%, specificity 42% for one plane of restricted movement). The trochanteric prominence angle test or craig test can be used for femoral neck anteversion assessment. | |||

[[Gluteal Tendinopathy|Gluteal tendinopathy]] is a very common finding on MRI in patients with pain in the buttock, lateral hip, and groin. Findings are focal tenderness, weak hip abduction, pain with passive and then resisted hip internal rotation with the hip flexed to 90° (Sen 88%, Spec 97.3%), and Pain on one-legged stance for 30 sec or more (Sen 100 % Spec 97.3%) | |||

;Lumbar Spine Examination | |||

{{main|Lumbar Spine Examination}} | |||

Facet Joints: Pay particular attention to any tenderness over specific facet joints, which may radiate down into the buttocks and posterior thigh. There may be be loss of spinal range of motion, and there may be more discomfort with extension than flexion. | |||

Discogenic pain: The McKenzie procedure is the best validated examination technique looking for pain centralisation with repeated movements but it requires going to a McKenzie course to do properly. passive straight leg raise (sensitivity 91%, specificity 26%), and slump tests (sensitivity 84%, specificity 83%) can be performed. | |||

=== Pelvic Malalignment === | === Pelvic Malalignment === | ||

Timgren et al assessed pelvic asymmetry in neurologic patients with symptoms that weren't explained by a neurological diagnosis. They found pelvic asymmetry in 87%. Reestablishment and maintenance of symmetry correlated with improvement in pain and function. An average of 3.7 appointments was needed. They found the following patterns. | Timgren et al assessed pelvic asymmetry in neurologic patients with symptoms that weren't explained by a neurological diagnosis. They found pelvic asymmetry in 87%. Reestablishment and maintenance of symmetry correlated with improvement in pain and function. An average of 3.7 appointments was needed. They found the following patterns. {{#pmid:16949945|timgren}} | ||

{| class="wikitable" | {| class="wikitable" | ||

| Line 110: | Line 124: | ||

Another difficulty is that imaging studies are often inconclusive, and there may not be degenerative changes in proven cases of sacroiliac joint pain. | Another difficulty is that imaging studies are often inconclusive, and there may not be degenerative changes in proven cases of sacroiliac joint pain. | ||

Hip radiographs are useful but 76% of patients with symptomatic sacroiliac joint pathology (confirmed by two fluoroscopically guided SI joint injections) have at least one abnormal finding on hip x-ray. A significant number also meet the diagnostic criteria for FAI.<ref>{{#pmid:23417531}}</ref> | Hip radiographs are useful but 76% of patients with symptomatic sacroiliac joint pathology (confirmed by two fluoroscopically guided SI joint injections) have at least one abnormal finding on hip x-ray. A significant number also meet the diagnostic criteria for FAI. Findings were hip OA (42%), subchondral cyst (45%), retroversion (21%), lateral CE angle >40 degrees (12%), coxa profunda (47%), CAM impingement (33%). <ref>{{#pmid:23417531}}</ref> | ||

==Diagnosis== | ==Diagnosis== | ||

The main differentials are hip pain, discogenic pain with or without radicular pain, and facetogenic pain, as per the clinical assessment section above. | The main differentials are hip pain, discogenic pain with or without radicular pain, and facetogenic pain, as per the clinical assessment section above. The elements of the diagnosis are a positive subjective history, positive provocative testing, lumbar spine and hip exam, and a positive single or ideally double diagnostic block. | ||

===Precision Diagnosis=== | ===Precision Diagnosis=== | ||

| Line 121: | Line 135: | ||

{{Sacroiliac Joint Pain DDX}} | {{Sacroiliac Joint Pain DDX}} | ||

The Altman criteria for [[[Hip Osteoarthritis|hip OA]] diagnosis (sensitivity 86%, specificity 75%)<ref>{{#pmid:2025304}}</ref> is | |||

*Hip IR ≥ 15 degrees, Pain with Hip IR | |||

*Morning stiffness for ≤ 60 min and Age > 50 years or | |||

*Hip IR < 15 degrees, and Hip Flexion ≤ 115 degrees | |||

[[Femoroacetabular Impingement|Femoroacetabular impingement]] is another important consideration, as is [[Hip Labral Tear|labral pathology]], however these entities being sources of pain is somewhat controversial, especially in the middle age and older. | |||

==Treatment== | ==Treatment== | ||

Revision as of 09:23, 23 August 2020

Sacroiliac joint pain, and sacroiliac joint dysfunction are common sources of chronic low back pain. Pain generators are the joint itself, and the surrounding ligaments and muscles. There may be multiple factors coming from the bones, ligaments, muscles, motor control, and alignment.

Anatomy

- Main article: Sacroiliac Joint Anatomy

The sacroiliac joint is a diarthrodial synovial joint, and only the anterior aspect is a true synovial joint. The posterior aspect is a syndesmosis that consists of the gluteus medius, gluteus minimus, sacroiliac ligaments, and piriformis. [1]

The anterior joint is thought to be innervated by the ventral rami of L4 and L5, and the posterior joint by the lateral branches of the posterior rami of L5-S4. The superior gluteal nerve contributes.

The joint can nutate (sacral base movement anteroinferior), counternutate (sacral base movement posterosuperior), and translate (linear motion). Multi-planar motion also occurs. These are all very small movements.

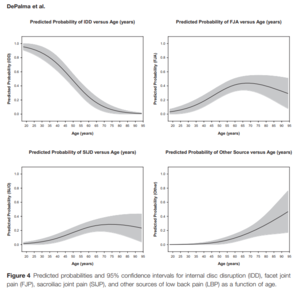

Epidemiology

The sacroiliac joint accounts for around 16% to 30% of causes of chronic low back pain. Some of the prevalence rates in diagnostic block research are 18% (DePalma 2011), 22.6% (Bernard 1987), 30% (Schwarzer 1995), 18.5% (Maigne 1996), 27% (Irwin 2007), 14.5% (Sembrano 2009).[2]

There are three primary groups of patients with sacroiliac joint pain and dysfunction. It occurs post lumbar fusion, in trauma, and in the peripartum. Pain can occur in all age groups from the very young to very old, but there is an increasing rate with age until approximately age 70 when it reverse. The mean age is not significantly different between facetogenic and sacroiliac joint pain, while discogenic pain is more common in younger patients.[2]

In symptomatic post-lumbar fusion patients, the sacroiliac joint is the source of pain about 30-40% of the time. Some of the prevalence rates in this context are 32% (Katz 2003), 35% (Maigne 2005), 43% (DePalma 2001), and 40% (Liliang 2011).[2]

Aetiology

- Post-lumbar fusion

Sacroiliac joint pain is almost akin to the idea of adjacent segment degeneration. In the event of L5-S1 fusion, there is 52% added motion on the sacroiliac joint. With L4-S1 fusion there is 168% added motion on the sacroiliac joint. Meanwhile if you fuse the sacroiliac joint, there is only 2-4% added motion on L4 and L5, and 5% added stress on the hip.[3] 75% of post-lumbar fusion patients have SI joint degenerative change on CT 5 years later, compared to 38% of controls.[4]

- Multi-level fusion

The more spinal levels that are fused, the higher the stress transfer to the adjacent segment, and the greater the rate of sacroiliac joint pain post-operatively. Rates are 5.8% (1 segment fused), 10% (2 segments), 20% (3 segments), and 22.5% (4+ segments).[3][5]

- Trauma

A very common cause of sacroiliac joint pain is a rear-end accident. The mechanism is from hitting the brake, getting hit from the back with an extended leg, and the leg gets forced back. Another common mechanism is missing a step, with force transmission right up the leg to the side. It can also occur with falling on the buttock, twisting, and traction injuries.

- Laxity of the SI joint and pregnancy

- Repetitive forces on the SI joint and supporting structures

- Biomechanical abnormalities

Such as leg length difference, pelvic obliquity, scoliosis, iliac crest bone graft

- Post infection degeneration

Clinical Assessment

There are many challenges with diagnosis, relating to the clinical assessment, imaging studies, and precision diagnosis.

History

Sacroiliac joint symptoms overlap with lumbar spine and hip pain symptoms. Sacroiliac joint pain is typically felt a bit lower than for discogenic and facetogenic pain, but there is significant overlap. There may be somatic referred pain down the leg, and into the groin, but is not normally as prominent. Hip joint pain can very commonly cause posterior pain, with the most common patterns in descending frequency: Buttock and thigh, buttock and groin, buttock alone, groin alone, and groin and thigh.[6][2]

Buttock, PSIS pain is present in 94%, lower lumbar pain in 72%, groin pain in 14%, lower extremity pain in 28%, upper lumbar in 6%, abdomen in 2%, and foot in 12%. [1]

An important consideration is that the sacroiliac joint pain pattern varies depending on the affected section of the sacroiliac joint.[7]

It is important to get details of any prior trauma, spinal fusion, and pregnancy history. See the pathophysiology section above.

Exacerbating activities can be divided into unilateral weight bearing (putting on socks/shoes, ascending/descending stairs, getting in/out of car, prolonged walking), sexual intercourse pain, pain with transitional movements (supine to painful side, sit to stand, rolling over in bed, getting in/out of bed), and pain while stationary (sitting on affected side, prolonged standing/sitting).[8]

Common relieving factors are bearing weight on the unaffected side, lying on the unaffected side, and manual or belt stabilisation.[8]

Sacroiliac joint dysfunction can cause neurological symptoms such as numbness, tingling, and weakness.[9]

Examination

- Main article: Sacroiliac Joint Examination

Complete inspection, palpation, range of motion, gait, and neurological tests.

Asking the patient to point where their primary pain is called the "Fortin finger test" is a test of pointing within 1cm inferomedial of the PSIS, consistent over at least 2 trials (e.g. beginning and end of exam). If the pointed area is below L5 then consider the sacroiliac joint. If it is above L5 then consider lumbar spine aetiology.[10] Tenderness over the PSIS and sacral sulcus may be a good indicator of a pain source.

Do a single leg stance, functional testing (stairs, sit to stand), active straight leg raise, and provocative testing. There may be a lurching and hobbling gait.

Provocative testing involves the distraction test, thigh thrust test, FABER test, and compression test. 2 out of 4 positive tests confer a higher likelihood of the sacroiliac joint being the source of pain (sensitivity 88%, specificity 78%, LR+ 4.0, LR- -0.16).[11] The provocative tests should be done in gradual increasing stages of pressure, stopping when positive.

The active straight leg raise test was studied in pregnancy to test for functional pelvic stability (sensitivity 87%, specificity 94%).[12]

- Hip Examination

- Main article: Hip Examination

It is very important to do a hip examination. Examine FABER (pain anterior for intra-articular hip pathology, sensitivity 88%), Scour (for hip OA and other pathologies, sensitivity 62-91%, specificity 43-75%s), and FADIR (for FAI and labral tears, sensitivity 75%, specificity 43%). The rare pririformis syndrome can be tested for with the FAIR test (sensitivity 88%, specificity 83%). The most predictive finding for osteoarthritis is restriction of internal rotation (severe OA sensitivity 100%, specificity 42% for one plane of restricted movement). The trochanteric prominence angle test or craig test can be used for femoral neck anteversion assessment.

Gluteal tendinopathy is a very common finding on MRI in patients with pain in the buttock, lateral hip, and groin. Findings are focal tenderness, weak hip abduction, pain with passive and then resisted hip internal rotation with the hip flexed to 90° (Sen 88%, Spec 97.3%), and Pain on one-legged stance for 30 sec or more (Sen 100 % Spec 97.3%)

- Lumbar Spine Examination

- Main article: Lumbar Spine Examination

Facet Joints: Pay particular attention to any tenderness over specific facet joints, which may radiate down into the buttocks and posterior thigh. There may be be loss of spinal range of motion, and there may be more discomfort with extension than flexion.

Discogenic pain: The McKenzie procedure is the best validated examination technique looking for pain centralisation with repeated movements but it requires going to a McKenzie course to do properly. passive straight leg raise (sensitivity 91%, specificity 26%), and slump tests (sensitivity 84%, specificity 83%) can be performed.

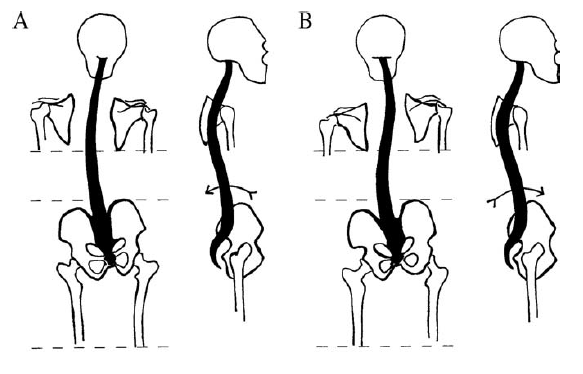

Pelvic Malalignment

Timgren et al assessed pelvic asymmetry in neurologic patients with symptoms that weren't explained by a neurological diagnosis. They found pelvic asymmetry in 87%. Reestablishment and maintenance of symmetry correlated with improvement in pain and function. An average of 3.7 appointments was needed. They found the following patterns. [9]

| Innominate | A. Posterior rotation | B. Anterior Rotation |

|---|---|---|

| Iliac Crest | Elevated ↑ | Elevated ↑ |

| ASIS | Elevated ↑ | Depressed ↓ |

| PSIS | Depressed ↓ | Elevated ↑ |

| scapula | Depressed ↓ | Elevated ↑ |

| leg | Longer ↑ | Shorter ↓ |

| 10-15mm lift | Increased crest difference ↑ | Reduced crest difference ↓ |

| Spinal curvature | C type scoliosis | S type scoliosis |

| C0-C1 function | Symmetric rotation in flexion | Restricted rotation in flexion |

All changes are in reference the ipsilateral side.

Rising of the crest upon anterior SI rotation is paradoxical, and its explanation cannot be reduced to a two-dimensional model.

Schamberger’s rule of the five Ls, which relates to the side of the anteriorly rotated innominate: “Leg Lengthens Lying, Landmarks Lower” (supine vs long sitting) [13]

Imaging

Another difficulty is that imaging studies are often inconclusive, and there may not be degenerative changes in proven cases of sacroiliac joint pain.

Hip radiographs are useful but 76% of patients with symptomatic sacroiliac joint pathology (confirmed by two fluoroscopically guided SI joint injections) have at least one abnormal finding on hip x-ray. A significant number also meet the diagnostic criteria for FAI. Findings were hip OA (42%), subchondral cyst (45%), retroversion (21%), lateral CE angle >40 degrees (12%), coxa profunda (47%), CAM impingement (33%). [14]

Diagnosis

The main differentials are hip pain, discogenic pain with or without radicular pain, and facetogenic pain, as per the clinical assessment section above. The elements of the diagnosis are a positive subjective history, positive provocative testing, lumbar spine and hip exam, and a positive single or ideally double diagnostic block.

Precision Diagnosis

Sacroiliac joint diagnostic injection is the gold standard method of diagnosis, ideally single blind dual blocks.[15] This is recommended in guidelines from multiple pain societies (IASP, AAMP&R, ASIPP-IPM, ASA, ASRA, SIS, WIP). It is extremely important that this happens before considering radiofrequency neurotomy or sacroiliac joint fusion. ISASS and ASIPP utilise >50% reduction in pain as the threshold, while NASS utilises >75% reduction.

Serious consideration should be given to a diagnostic intra-articular hip joint injection to exclude the hip as a source of pain.

- Sacroiliac ligament pain (interosseous or dorsal ligaments)

- Mechanical

- Locking

- Hypermobility

- Osteoarthritis

- Following Lumbosacral fusion

- Fracture

- Tumour

- Rheumatological disorders

- Axial spondyloarthritis

- Psoriatic arthritis

- Infection

- Myofascial pain (Quadratus Lumborum, Gluteus Maximus, Piriformis, Levator Ani)

- Secondary causes: Discogenic pain, Facet joint pain, Hip disease, Spinal stenosis, Flail coccyx (coccydynia), S1 foraminal stenosis

The Altman criteria for [[[Hip Osteoarthritis|hip OA]] diagnosis (sensitivity 86%, specificity 75%)[16] is

- Hip IR ≥ 15 degrees, Pain with Hip IR

- Morning stiffness for ≤ 60 min and Age > 50 years or

- Hip IR < 15 degrees, and Hip Flexion ≤ 115 degrees

Femoroacetabular impingement is another important consideration, as is labral pathology, however these entities being sources of pain is somewhat controversial, especially in the middle age and older.

Treatment

Manual therapy may be the most effective initial treatment modality. In a single blind randomised trial of 51 patients with sacroiliac joint related back and leg pain, 56% were successfully treatment. Physiotherapy was successful in 3 out of 15 (20%), manual therapy in 13 out of 18 (72%), and intra-articular injections in 9 out of 18 (50%). Manual therapy consistent of two sessions of high-velocity thrust SIJ manipulation with an interval of 2 weeks. The injection arm was a fluoroscopically guided lidocaine and triamcinolone injection. [17]

Conservative treatment includes medication, physical therapy, SI joint belt, therapeutic SI joint injections (steroid, or prolotherapy). Higher on the treatment intensity continuum is radiofrequency neurotomy, minimally invasive sacroiliac joint fusion, and open sacroiliac joint fusion. It is uncommon that conservative management fails and surgery is required.

Manual Therapy

Alignment can be reacquired through various means such as muscle energy techniques, and mobilisation with movement.

Mulligan Techniques

- Anterior Innominate Rotation

The most common malalignment is anterior rotation. This can usually be easily corrected with a mobilisation with movement technique called anterior innominate extension in lying mobilisation with movement. The sacrum is stabilised, the innominate is rotated and glided posteriorly, while the patient extends in lying. Ensure mobilisation is a combination of glide +/- rotation of the innominate with opposing forces on the sacrum. This technique often corrects posterior rotation, too.

- Mulligan Videos

Muscle Energy Techniques

Pelvic asymmetries can also be corrected with muscle energy techniques.

- Anterior Innominate Rotation

The technique can be visualised via the image below where the origin and insertion of the hamstrings are reversed to pull and rotate the innominate. Ensure to lean cranially, and allow some abduction of the ipsilateral hip. Stabilise the contralateral ASIS. Reach the end range of hip flexion and complete a muscle energy technique. The patient can treat themselves by grasping under their knees and resisting thigh extension, alternating on both sides. This again produces a correctional rotational force on the pelvis.

HVLA techniques

High-velocity and low-amplitude thrust technique can be applied through the ankle on the side of the dysfunctional SI joint

Injections

- Main article: Sacroiliac Joint Injection

Radiofrequency Neurotomy

- Main article: Sacroiliac Joint Precision Treatment

The sacroiliac joint can treated with radiofrequency neurotomy after a confirmatory single or dual diagnostic block. Cooled radiofrequency neurotomy has an evidence base, while traditional radiofrequency does not.

Surgery

Minimally invasive iFUSE fusion using fluoroscopy is actually another precision treatment proven in two large industry-funded RCTs, as the study population had diagnostic blocks. (See precision treatment article) It has rapid pain relief (~50 point improvement), and functional improvement (~30 point ODI improvement), high patient satisfaction (>90%), superior outcomes to non-surgical management, durable outcomes (5 year follow up), low revision rate (<5%), better outcomes than open fusion, and is cost-effective.[18][19]

For open surgery, long construct failures can manifest as pseudoarthrosis, rod and screw failure, infection, screw prominence, sacroiliac joint pain, and neurological symptoms. The traditional single bolt through the sacroiliac joint does not stabilise the joint. Pelvic fixation has a failure rate of 29.5% (ISSG database, iliac screw = 287, sacral alar screws = 131). The failure rate of lumbopelvic fixation after long construct fusions in adults with spinal deformity is 34.3%. Risk factors for major failures are large pelvic incidence, revision surgery, and failure to restore lumbar lordosis and sagittal balance.[20]

Videos

Article Downloads

- Timgren et al 2006 - Reversible Symptomatic Pelvic Asymmetry and Neurologic Symptoms

- Genne' DeHenau McDonald powerpoint presentation

References

- ↑ 1.0 1.1 Vanelderen et al.. 13. Sacroiliac joint pain. Pain practice : the official journal of World Institute of Pain 2010. 10:470-8. PMID: 20667026. DOI.

- ↑ 2.0 2.1 2.2 2.3 2.4 DePalma et al.. What is the source of chronic low back pain and does age play a role?. Pain medicine (Malden, Mass.) 2011. 12:224-33. PMID: 21266006. DOI.

- ↑ 3.0 3.1 Ivanov et al.. Lumbar fusion leads to increases in angular motion and stress across sacroiliac joint: a finite element study. Spine 2009. 34:E162-9. PMID: 19247155. DOI.

- ↑ Ha et al.. Degeneration of sacroiliac joint after instrumented lumbar or lumbosacral fusion: a prospective cohort study over five-year follow-up. Spine 2008. 33:1192-8. PMID: 18469692. DOI.

- ↑ Unoki et al.. Fusion of Multiple Segments Can Increase the Incidence of Sacroiliac Joint Pain After Lumbar or Lumbosacral Fusion. Spine 2016. 41:999-1005. PMID: 26689576. DOI.

- ↑ Lesher et al.. Hip joint pain referral patterns: a descriptive study. Pain medicine (Malden, Mass.) 2008. 9:22-5. PMID: 18254763. DOI.

- ↑ Kurosawa et al.. Referred pain location depends on the affected section of the sacroiliac joint. European spine journal : official publication of the European Spine Society, the European Spinal Deformity Society, and the European Section of the Cervical Spine Research Society 2015. 24:521-7. PMID: 25283251. DOI.

- ↑ 8.0 8.1 Janda V. On the concept of postural muscles and posture in man. Aust J Physiotherapy. 1983;29:83-90

- ↑ 9.0 9.1 Timgren & Soinila. Reversible pelvic asymmetry: an overlooked syndrome manifesting as scoliosis, apparent leg-length difference, and neurologic symptoms. Journal of manipulative and physiological therapeutics 2006. 29:561-5. PMID: 16949945. DOI.

- ↑ Fortin & Falco. The Fortin finger test: an indicator of sacroiliac pain. American journal of orthopedics (Belle Mead, N.J.) 1997. 26:477-80. PMID: 9247654.

- ↑ Laslett et al.. Diagnosis of sacroiliac joint pain: validity of individual provocation tests and composites of tests. Manual therapy 2005. 10:207-18. PMID: 16038856. DOI.

- ↑ Mens et al.. Reliability and validity of the active straight leg raise test in posterior pelvic pain since pregnancy. Spine 2001. 26:1167-71. PMID: 11413432. DOI.

- ↑ Wolf Schamberger. The Malalignment Syndrome 2nd Edition. Churchill Livingstone. 2012

- ↑ Morgan et al.. Symptomatic sacroiliac joint disease and radiographic evidence of femoroacetabular impingement. Hip international : the journal of clinical and experimental research on hip pathology and therapy 2013. 23:212-7. PMID: 23417531. DOI.

- ↑ Szadek et al.. Diagnostic validity of criteria for sacroiliac joint pain: a systematic review. The journal of pain : official journal of the American Pain Society 2009. 10:354-68. PMID: 19101212. DOI.

- ↑ Altman et al.. The American College of Rheumatology criteria for the classification and reporting of osteoarthritis of the hip. Arthritis and rheumatism 1991. 34:505-14. PMID: 2025304. DOI.

- ↑ Visser et al.. Treatment of the sacroiliac joint in patients with leg pain: a randomized-controlled trial. European spine journal : official publication of the European Spine Society, the European Spinal Deformity Society, and the European Section of the Cervical Spine Research Society 2013. 22:2310-7. PMID: 23720124. DOI. Full Text.

- ↑ Polly et al.. Two-Year Outcomes from a Randomized Controlled Trial of Minimally Invasive Sacroiliac Joint Fusion vs. Non-Surgical Management for Sacroiliac Joint Dysfunction. International journal of spine surgery 2016. 10:28. PMID: 27652199. DOI. Full Text.

- ↑ Dengler et al.. Randomized Trial of Sacroiliac Joint Arthrodesis Compared with Conservative Management for Chronic Low Back Pain Attributed to the Sacroiliac Joint. The Journal of bone and joint surgery. American volume 2019. 101:400-411. PMID: 30845034. DOI. Full Text.

- ↑ Cho et al.. Failure of lumbopelvic fixation after long construct fusions in patients with adult spinal deformity: clinical and radiographic risk factors: clinical article. Journal of neurosurgery. Spine 2013. 19:445-53. PMID: 23909551. DOI.

Literature Review

- Reviews from the last 7 years: review articles, free review articles, systematic reviews, meta-analyses, NCBI Bookshelf

- Articles from all years: PubMed search, Google Scholar search.

- TRIP Database: clinical publications about evidence-based medicine.

- Other Wikis: Radiopaedia, Wikipedia Search, Wikipedia I Feel Lucky, Orthobullets,